"Kamaishi has the rugby power."

About 50 days before the opening day of the 2019 Rugby World Cup, banners can be seen everywhere on the main street in Kamaishi, one of 12 host cities for the event.

Traditionally, Kamaishi has been known as a "rugby town" because of the Nippon Steel Kamaishi rugby club, which won seven straight national championships from 1979 to 1985. The team, however, folded in 2001 and its history and traditions were succeeded by the Kamaishi Seawaves, a Top Challenge League team.

Along with its local seafood products and steel, rugby is one of the things that Kamaishi citizens are most proud of. The sport has helped give them the energy to recover from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake.

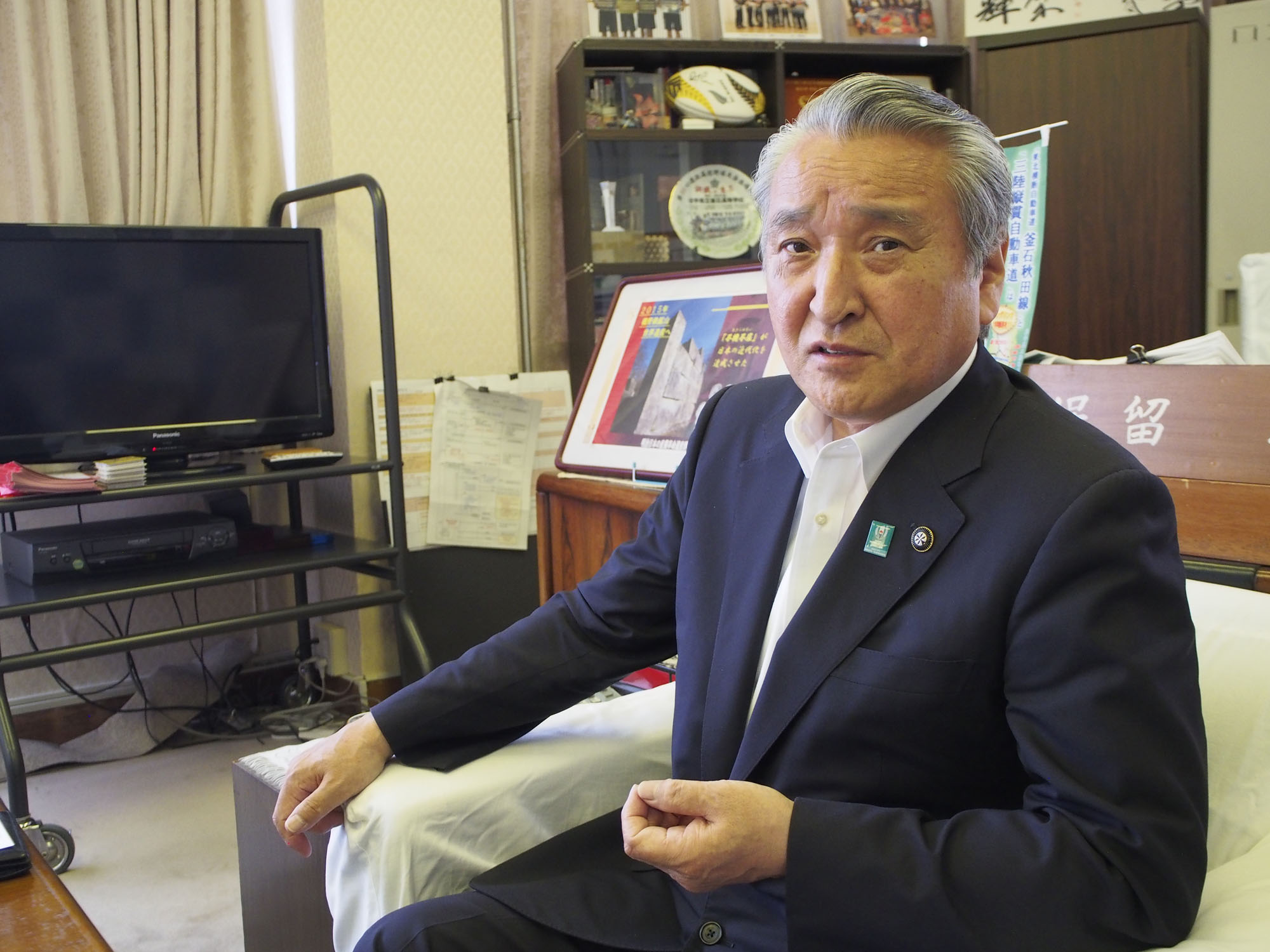

And Kamaishi Mayor Takenori Noda is one of the believers in rugby power during the ongoing recovery.

"We have worked tirelessly and reached this point after eight years and four months after the 2011 disaster," Noda said in an exclusive interview with The Japan Times at Kamaishi City Office on July 26.

"We can't say the recovery is fully done yet because a lot of people are still forced to live in temporary houses. But we can say we have made progress in restoring operations of infrastructure and we could not imagine this eight years ago."

A total of 993 people died and another 152 are still missing in Kamaishi after the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami. The city was severely damaged, including the Unosumai area where an elementary school and a junior high school were destroyed.

Kamaishi Recovery Memorial Stadium, which will two host World Cup matches this fall, was built on the site of the destroyed schools.

"We saw a car sticking into the third floor of a building there," Noda recalled. "It is almost a miracle how we built a rugby stadium there and will bring people around the world to the venue. We can proudly show the world how we have made progress in the past eight years. I believe it's the same for the other disaster areas in Iwate and Miyagi prefectures. We want to express our thanks to the world for helping us and it is to show them how we have progressed by now."

In 2009, Japan won the right to host the Rugby World Cup. It could be natural that Kamaishi citizens relied on the hopes of becoming one of the host cities to cheer up the people of the town and help make progress in its recovery. By the end of 2011, nine months after the disaster, multiple volunteer organizations established and promoted by citizens to host the World Cup developed some strength.

And it didn't take long until that power moved politics, with Noda deciding that Kamaishi would try to become a host city.

"We came up with a 10-year recovery plan in October or November of 2011, the year of the disaster," explained Noda, who became the mayor in 2007 and is now in his third four-year term. "The plan included a lot of things that we had done. Such as getting Hashino Iron Mining and Smelting Site selected for the World Heritage Site, inviting Rugby World Cup and inviting the large commercial complexes.

"It looked like tough goals to achieve at that time. But I believed making the effort will leave positive effects on Kamaishi. I made the recovery plan based on the belief. I bet on possibilities. I bet on hosting the World Cup. I could have gotten criticized if we had failed. But we cannot call it recovery if we do not make enough progress to host the World Cup. We set a goal to make efforts and recovery well enough to be able to be a host city. We believed the mindset helps our recovery."

An expensive endeavor

It is true that some people in Kamaishi and Iwate Prefecture opposed Noda's recovery plan. Some victims questioned the decision to spend money to host the World Cup. The host plan included building a new stadium, whose original cost was an estimated ¥2.7 billion. Kamaishi was the only city among the 15 candidates that did not already have a World Cup-level stadium.

The price tag rose to ¥3.9 billion due to additional work that was needed in order to meet the Rugby World Cup's stadium regulations.

"The most difficult part was getting the consensus of the citizens," Noda said. "None of us was sure what we would be eight years later. We were not sure if we could reconstruct roads, get houses rebuilt, or earn enough money to cover the cost. But you can't go forward without a goal. If you have a goal, trying to achieve it would never disturb our effort of recovery.

"That was kind of my intuition as a politician. I bet on it. A goal helps you progress. Based on the belief, I preached to people and they gradually showed their understanding. And now some 20,000 people are joining in volunteer activities of the World Cup. Our population is 34,000. You can say most Kamaishi citizens are involved with the World Cup in some ways," Noda added. " Fortunately, we got the cooperation from (former Prime Minister and Japan Rugby Football Union chairman) Yoshiro Mori, the JRFU, the Reconstruction Agency and Iwate Prefecture. We have come this far, but it was only because many people helped us."

The World Heritage Committee recognized Hashino Iron Mining and Smelting Site as the Site of Japan's Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining in March 2015, the same month that Kamaishi was selected as a host city.

"It was a 'Kamaishi year,' " Noda said.

Asked why rugby was important for the recovery of Kamaishi, Noda simply answered, "Hopes."

"For us, especially aged people, Kamaishi is the rugby town. Kamaishi equals rugby," Noda said. "We have the tradition of Nippon Steel Kamaishi and its red jersey. We want to connect the tradition to the next generation. Hosting the World Cup here in Kamaishi helps that. In that regard, we are fortunate that we have rugby in this town.

"I noticed the spirit of the popular phrase in Japanese rugby, 'One for All, All for One' can be applied to the recovery. Without a town's recovery, there is no recovery for individuals. Without individuals' recoveries, there is no recovery for the town."

Noda's father, Takeyoshi, also served as mayor of Kamaishi (1987 to 1999), but that fact made the younger Noda stay away from politics. Instead, he became the principal of a Kamaishi kindergarten. But ironically, experiences there made Noda turn to politics.

"As the principal, I saw the number of children decreasing," Noda said. "Kindergarten reflects everything in society. Children reflect their family. I realized a lot of issues and I felt the need to do something about it. I chose an occupation away from politics but, in the end, I have been connected with politics."

It happened during a difficult time in Kamaishi history.

"This city was seriously damaged by bombardment from the warships (during the World War II), and tsunami in Meiji and Showa eras. And we had the 2011 disaster," Noda said. "But people of Kamaishi have repeatedly recovered. They never gave up. This World Cup is also the extension of history with a 'we never give up' slogan. Continuing this spirit to make the recovery is the legacy of Kamaishi."

Yoshimune Satake contributed to this article.