Three years after describing NATO as "brain dead,” Emmanuel Macron is once again playing trans-Atlantic irritant.

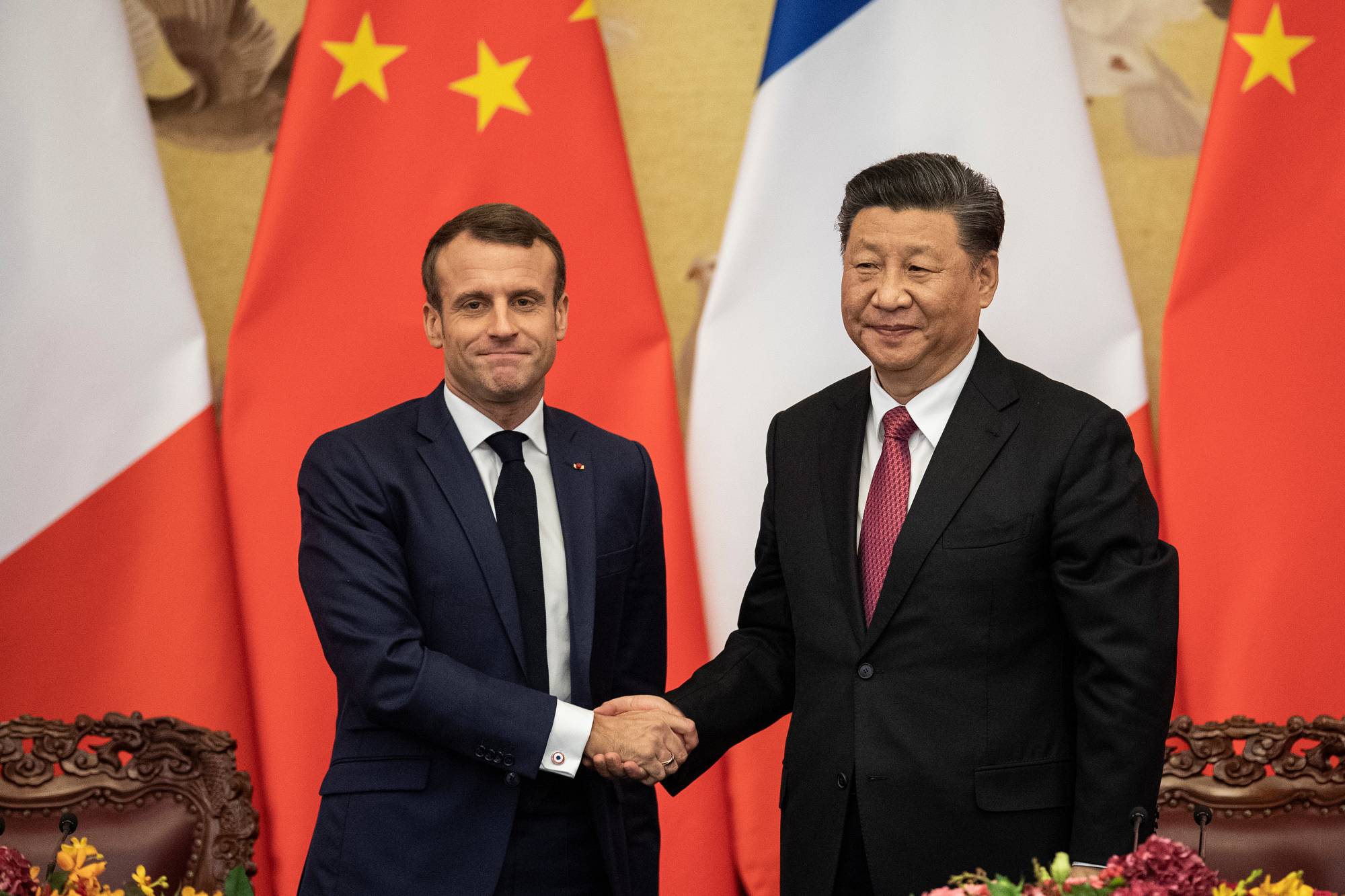

After a recent trip to China that was heavy on business contracts and light on geopolitical wins, the French president has annoyed allies from the Baltic to the Beltway by saying Europeans should stand apart from the U.S. on China and Taiwan or risk becoming "vassals.”

This is not the first De Gaulle-style flourish from a French leader looking to steer Europe down a less Atlanticist path. What makes this different is the timing: The Ukraine war has entered its second grueling year, the U.S. is heading into new elections and Europe’s post-Cold War dependence on Washington has never been more obvious.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.