Difficulties with Iran will recur regularly, like the oscillations of a sine wave, and the recent crisis — if such it was, or is — illustrates persistent U.S. intellectual and institutional failures, starting with this: The Trump administration's assumption, and that of many in Congress, is that if the president wants to wage war against a nation almost the size of Mexico (and almost four times larger than Iraq) and with 83 million people (more than double that of Iraq), there is no constitutional hindrance to him acting unilaterally.

In April, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was pressed in a Senate hearing to pledge that the administration would not regard the 2001 authorization for the use of military force against al-Qaida and other nonstate actors responsible for 9/11 as authorization, 18 years later, for war against Iran. Pompeo laconically said he would "prefer to just leave that to lawyers." Many conservatives who preen as "originalists" when construing all the U.S. Constitution's provisions other than the one pertaining to war powers are unimpressed by the framers' intention that Congress should be involved in initiating military force in situations other than repelling sudden attacks.

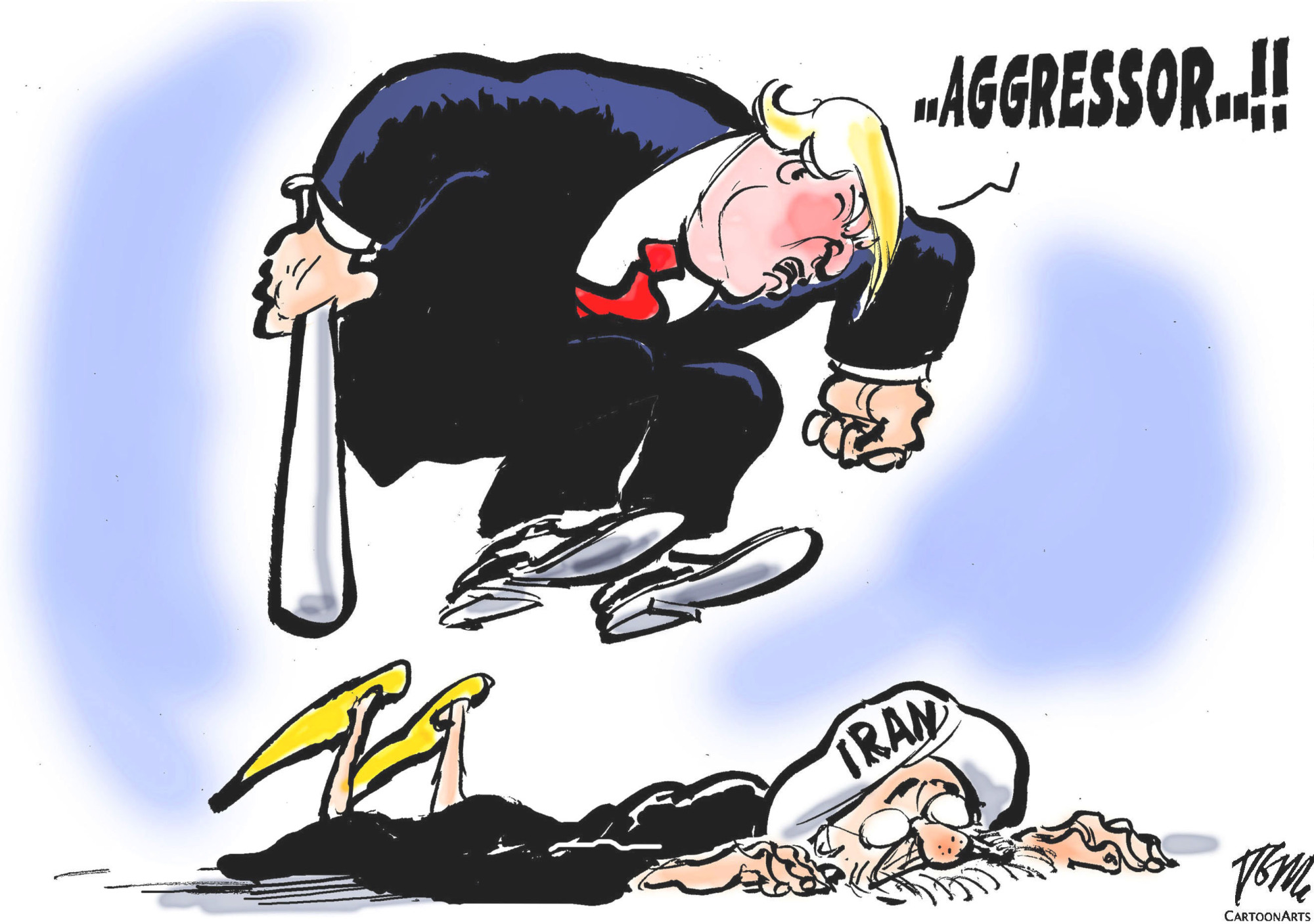

The Economist, which is measured in its judgments and sympathetic to America, tartly referred to the supposed evidence of Iran's intentions to attack U.S. forces, allies or "interests" as "suspiciously unspecific." Such skepticism, foreign and domestic, reflects 16-year-old memories of certitudes about Iraq's weapons of mass destruction: remember Secretary of State Colin Powell spending days at the CIA receiving assurances about the evidence. There also are concerns about the impetuosity of a commander in chief who vows that military conflict would mean "the official end" of Iran, whatever that means.