When former Chinese Army officer Ren Zhengfei founded Huawei in 1987, his business plan appears to have been relatively simple. By reverse-engineering foreign-built phone switches and other basic telecoms equipment, the firm could undercut global rivals and become a worldwide market leader. For the first three decades of its life, that strategy appeared to serve the firm just fine. By 2011, Huawei was operating in more than 170 countries, serving 45 of the world's largest 50 telecom providers and reaching about a third of the world's population.

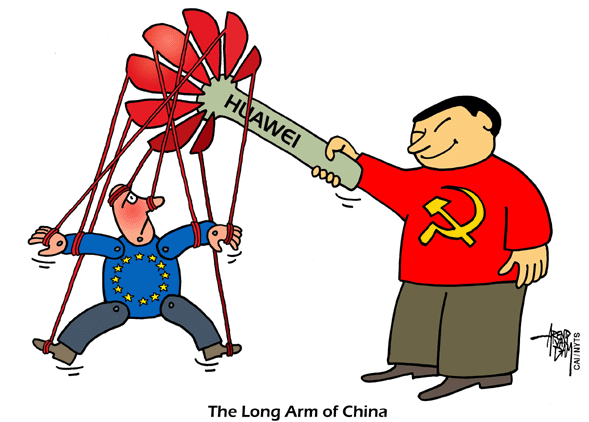

More recently, however, the strategy has started to unravel. Seen as too close to the Chinese government, the company finds itself at the heart of a growing geopolitical confrontation between Beijing and Washington. It stands accused of allowing various forms of Chinese state espionage, while its chief financial officer is on bail in Canada after being arrested on a U.S. warrant last year. Whatever the truth of such allegations, it has become simply too controversial and distrusted for a growing number of nations to work with.

The company denies wrongdoing and says it remains independent of the Chinese authorities. In many respects, however, that barely matters. The saga — which now includes a series of lawsuits and political crises — points to a much larger trend, one that challenges almost all companies which thrived on unfettered globalization. In an environment of growing international distrust and geopolitical tension, it is simply becoming more difficult for large firms to operate worldwide without facing serious political headwinds in many jurisdictions.