The samurai sword has long been a symbol of great allure in Japan. It conjures images of virility, tradition, austerity and the mystery of legends. Not only is it said that the Shinto gods possessed swords but, as part of the Imperial regalia, such blades were believed to signify the divinity and divine origins of the Imperial family. Stories of sword-fought conquests date as far back as the "Kojiki," Japan's earliest written history from the year 712. And since then, as the embodiment of the samurai spirit, they have held an extremely important position in the iconography of Japanese culture.

"Meibutsu: Treasured Japanese Swords," organized by the Nezu Museum, showcases a rare collection of 52 swords on loan from a vast array of museums, private collectors and Shinto shrines throughout Japan. All the exhibits date back to Japan's "golden age" of sword making — during the 12th to the 14th centuries — and their features are emphasized by specially designed lighting that highlights intricate details and even helps show off the various characteristic colors that reflect off the polished blades.

The term "meibutsu," or "masterpiece sword," originated with the publication in 1719 of the "Kyoho Register" — a catalog commissioned by the eighth Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune (1684-1751), which listed for the first time the famous swords of Japan. The purpose of the register was to rank the swords in terms of their characteristics, which included each sword's origins, swordsmith, size and shape, design, defining features and cutting ability.

As the first official classification system, the register created a hierarchy that identified which swords were valuable and priceless. This led to the formalization of an already commonly accepted belief that, based on their historic lineage and their role in heroic battles, certain weapons were part of a "pantheon" of swords worthy of special recognition and fame.

During the 12th to 14th centuries, the samurai warrior class was the top tier of the feudal system, and it became customary for such warriors to carry swords at all times. Swordsmiths thus became more skilled, which led to the historical demarcation of this period as the golden age of sword making.

Swords were awarded for bravery in action, and as they became associated with victories in famous battles, they also became prized status symbols to the leaders of the warrior class. The practice of praying at Shinto shrines for victory in battle and bestowing swords to shrines as offerings to the gods also dates to this era.

Between the late 13th and the early 14th centuries, two master swordsmiths, Masamune and Yoshimitsu, came to the fore as the most skilled of their time. In an unparalleled opportunity to view the work of both these artisans, "Meibutsu" is showing 11 Masamune and six Yoshimitsu blades.

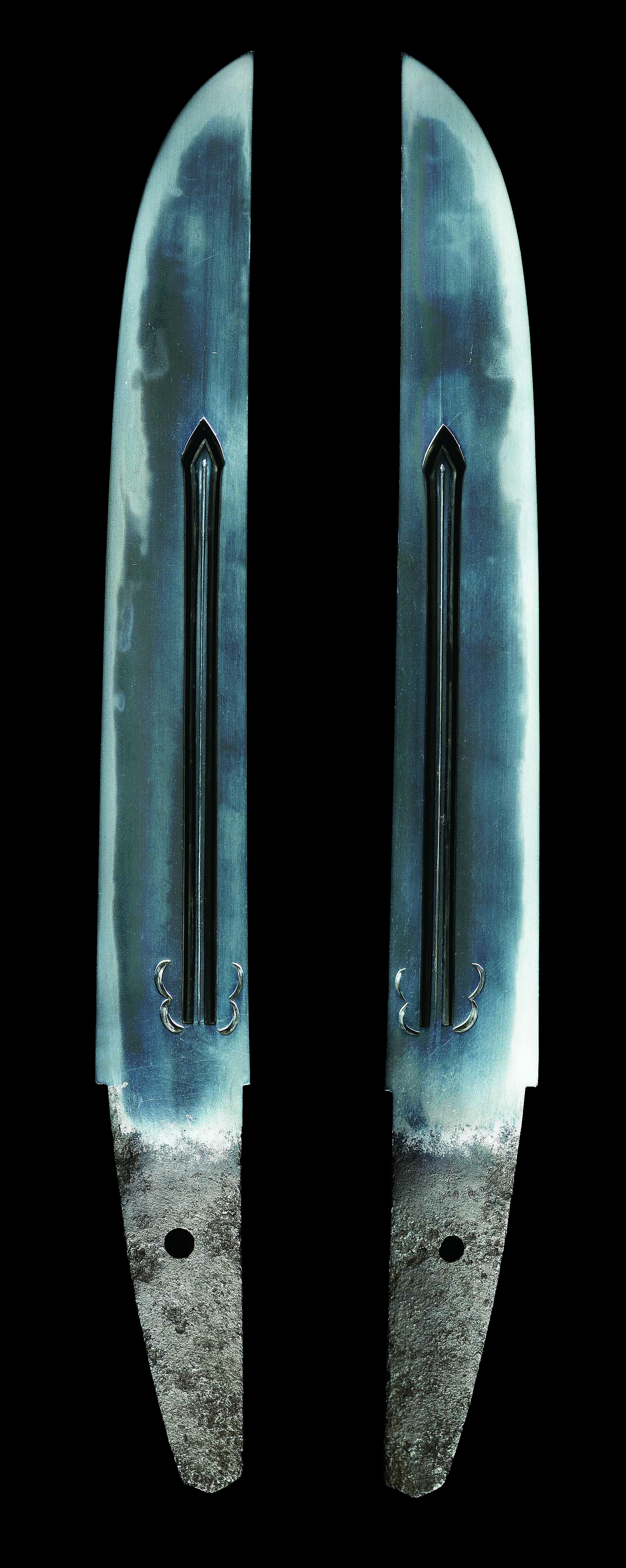

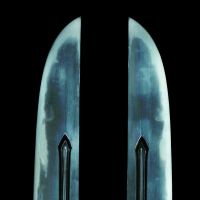

Both Masamune and Yoshimitsu had their own individual flair and style, which made their swords highly coveted. Masamune's specialty was to create temper lines on the blade that resembled the undulating waves of a raging sea. That undulating temper line was characteristic of his approach to designing swords for the warlords of the Kamakura shogunate (1192-1333). He chose to create dynamic lines that expressed movement and energy.

One Masamune example of particular note is a short sword (tantō). Historically known by the name Hocho Masamune, it is one of only three of the master's extant broad-blade short swords. What makes it unique is its unusual thinness and sharpness, as well as its original fretwork design that includes two parallel slots in the blade.

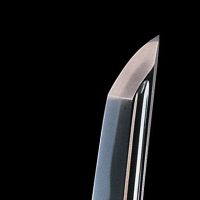

In contrast, Yoshimitsu — who lived in the old Imperial capital of Kyoto, where emperors and court nobles were the primary patrons of swordsmiths — produced more aristocratic and refined blades. Yoshimitsu's short swords exemplify this style with simple, straight temper lines in a delicate and visually slender form. The Yoshimitsu short swords in this exhibition display his characteristic straight lines, with the tip of the temper line gracefully turning back on itself in what is referred to in Japanese as a komaru-shaped curve, a feature unique to Yoshimitsu's swords.

During the Muromachi Period (1392-1573), a custom arose among warlords of giving their most highly prized swords to the shogun as a show of respect. Succeeding shoguns began to stockpile these swords, and since they symbolized strength, the reputation of a shogun was in large part judged by the number of illustrious swords he had in his possession.

Given the high regard accorded to swords by both shoguns and warlords, it is no surprise that master swordsmiths were regarded with great respect. The clear blue appearance of Masamune's and Yoshimitsu's blades symbolized purity for those who coveted them and they became the most highly prized onrdof their era. As a result, they were also considered the ultimate gift for a shogun.

This exhibition speaks of the bravery of individual warriors, the history of the Kamakura, Muromachi, and Tokugawa military reigns, and the aesthetic flair and stylistic choices of Japan's leaders during these periods. The legacy of such an impressive collection of masterpieces remains a testament to the age of the samurai and to its spirit.

"Meibutsu: Treasured Japanese Swords" runs till Sept. 25 at the Nezu Museum in Tokyo; admission ¥1,200; open 10 a.m.-5 p.m., closed Mon. For more information, visit www.nezu-muse.or.jp.