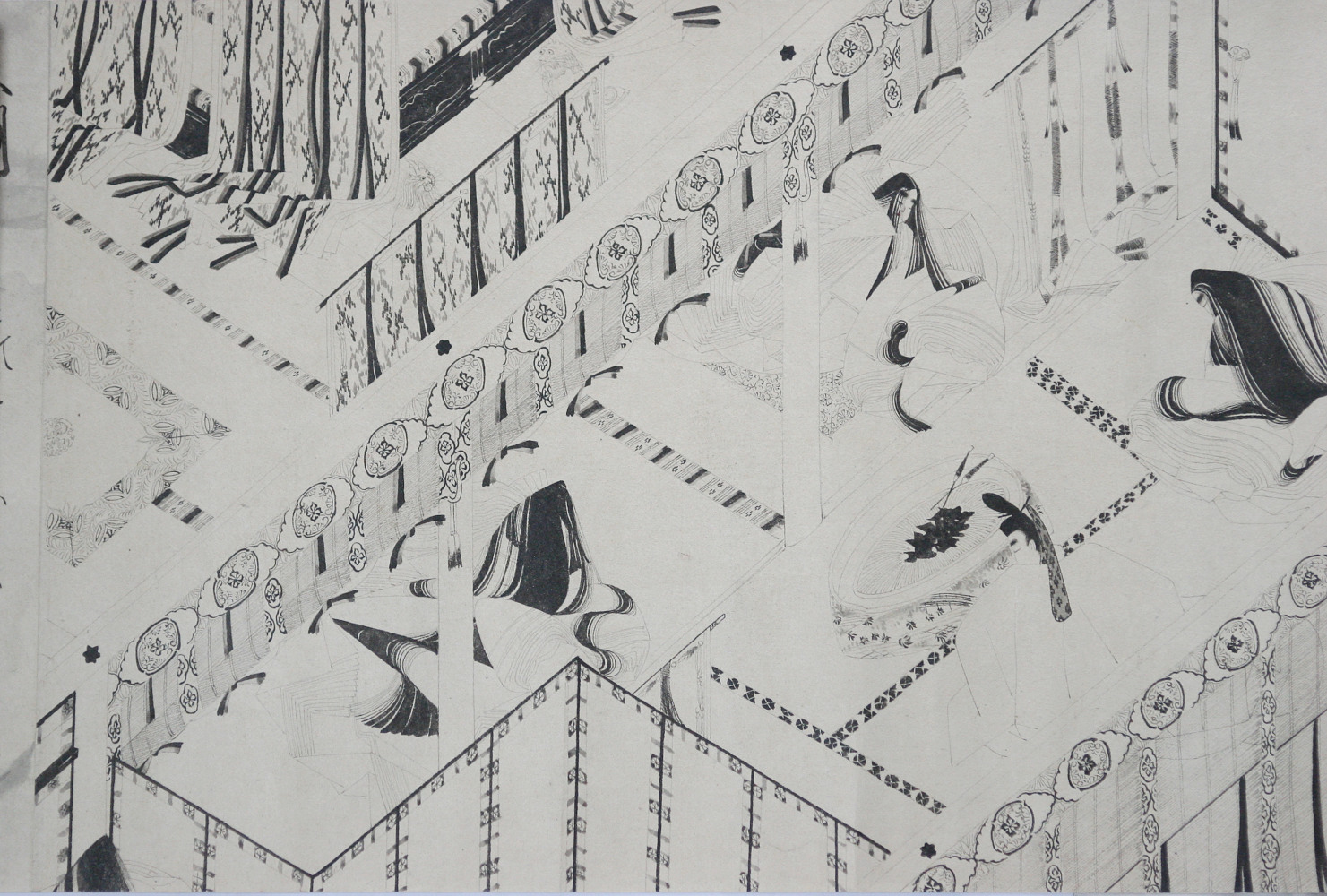

Once upon a time — the fairy tale opening is apt, though it's history we're dealing with — peace lay so thick upon the land that war was inconceivable. The capital was a city named "Peace and Tranquility" — Hei-An (modern-day Kyoto). There was a ministry of war, but the war minister was no fighter; nor was anyone else who mattered. A war minister has a major role in the classic 11th-century novel "The Tale of Genji" — his name is Kaoru (fragrance). He is described as being as beautiful as a woman and in a state of unabashed terror on journeys along deserted paths to a remote village. Imagine him on the field of battle! But there was no field of battle to imagine him on.

The Heian Period (794-1185) was not totally demilitarized. In contemporary literature soldiers are objects of pity and derision. "The more elegantly he tried to arrange things," we read of one in "Genji," "the more blatantly was his vulgar, boorish, countrified nature exposed. ... He knew nothing of music and the other pleasant sides of life, but he was an excellent shot with the bow." It's a skill that demeans rather than dignifies.

Four centuries of almost unbroken peace are an odd prelude to a martial tradition as fierce and courageous as any in the world. But so it was. The Heian aristocrat was not bred for war. He was — none more so than the fictional Genji, the "shining prince" — soft, refined, indolent, elegant, artistic, exquisitely sensitive; a poet, a calligrapher, a perfume-blender, a musician. He knew the beauty of things and he knew the sadness of things — knew, in short, that beauty, however beautiful, fades; that life, however fleetingly satisfying, is doomed. Why fight? What was there to fight for, in a world that was a mere "dream of a dream"?

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.