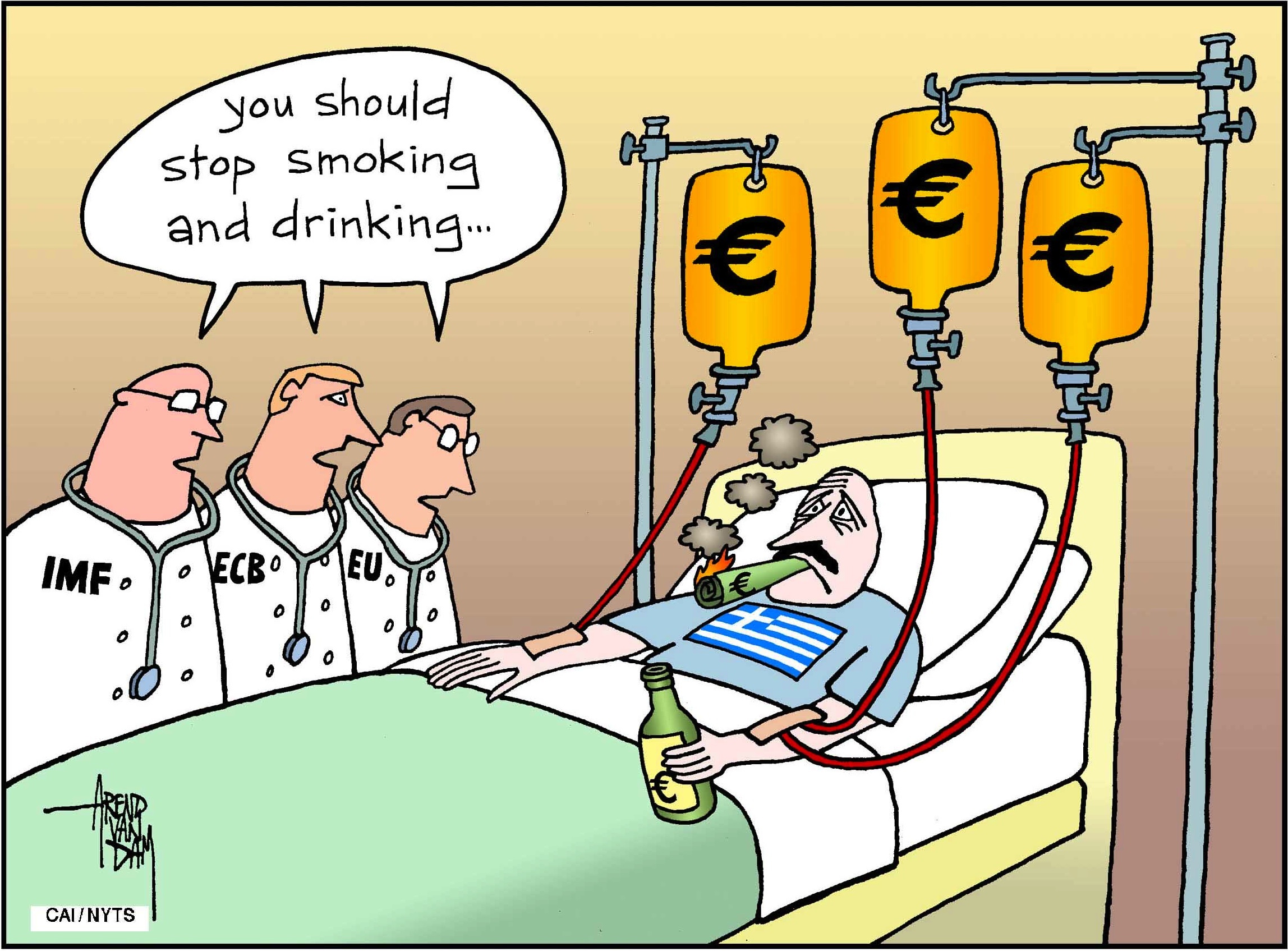

The deal European leaders struck with outmatched Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras on Monday will probably end in failure: It's hard to imagine a country that has not lost a war giving up its sovereignty to the extent that Tsipras has promised. The agreement has, however, demonstrated that a common currency like the euro has a low tolerance for democracy's wilder extremes.

Few remember the platform on which Tsipras's party, Syriza, came to power last January. The Thessaloniki Program proposed costly measures to rebuild the welfare state, spoke of the need to write off Greek debts as creditor nations did for Germany in 1953, and blasted Tsipras's predecessor, Antonis Samaras, for being too pliable: "We are ready to negotiate and we are working towards building the broadest possible alliances in Europe. The present Samaras government is once again ready to accept the decisions of the creditors. The only alliance which it cares to build is with the German government."

This reads like cruel irony now. Tsipras did not want an alliance with the Germans, but he has now agreed to let them and other Europeans control Greek ministries, veto bills and oversee a holding company set up to monetize — through selloffs and otherwise — Greece's most valuable state assets. The country will be under outside supervision as tight as that which Germany was forced to accept after it lost the war.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.