Poet Taneda Santoka (1882-1940) cut a pitiful, tragic figure. His mother's suicide when he was 11 seems to have unhinged him for life. After a failed marriage and a failed sake-brewing enterprise he took to drink and hit the road. Someone took pity on him and brought him to a Zen temple, where he studied and entered the priesthood. Unable to settle down, he embarked on a life of endless, aimless tramping. In priestly garb, he walked the backroads of rural southwestern Japan for years on end, begging his sustenance, sleeping at wretched wayside inns, drinking whenever and whatever possible, and — is this incongruous? — writing.

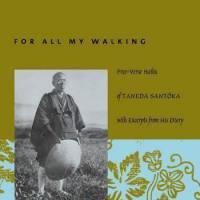

For All My Walking, by Taneda Santoka, Translated by Burton Watson.

Columbia University Press, Poetry.

The little snippets of poems he wrote have an uncanny power. Though classified as "free-verse haiku," all they share with traditional haiku is brevity.

A born poet will write of misery when his life overflows with it. He will transmute it into freedom and celebrate it. Santoka's celebration, however, can come perilously close to wallowing.

"Nearly run over / by a car / cold cold road," he writes, and, "Nice road / going to a nice building / crematorium."

Then there's this:

"The deeper I go / the deeper I go / green mountains"

What are those green mountains? The ultimate goal that redeems all suffering? Or a symbol of that suffering, as in: "Nothing but green mountains, what a wasted, futile life!"

Read archived reviews of Japanese classics at jtimes.jp/essential.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.