The newest and 11th edition of the Biwako Biennale in Shiga Prefecture kicks off on Sept. 20, running for almost two months until Nov. 16. One of the oldest regional art festivals in Japan, the Biwako Biennale has been a part of The Japan Cultural Expo 2.0 since 2020.

This year, the theme is “Flux,” reminding us that the world as we know it is in a constant state of change and flow. The biennale celebrates the state of flux with the works of 70 artists from around the world and its spirit is perfectly in keeping with the The Japan Cultural Expo 2.0’s objective: an invitation to share in the joys of Japan’s richly diverse art scene.

Biennale’s inception

This festival has a formidable history. Unlike other regional art festivals often funded by prefectural governments and corporations, the Biwako Biennale is a largely independent entity launched by Yoko Nakata.

Nakata is one of the pioneers of Japan’s regional art festivals. For the past 24 years, she has been helming the Biwako Biennale, nurturing, supporting and supervising the event as it grew in scale and prominence. Her role as art director extends far beyond the borders of event production and her efforts have transformed the historic but too-quiet backwater of Omihachiman into a cultural hub of international repute.

“When I first decided to hold the Biwako Biennale here, the residents didn’t even know what a biennale was,” Nakata said with a laugh. “But I knew that the city of Omihachiman, with its incredible history and beautiful natural landscapes, would be a perfect setting for this endeavor.”

Venues draped in history, nature

Centuries ago, Omi was the former name of Shiga Prefecture, and the merchants in this area prospered by transporting goods via Lake Biwa, the largest freshwater lake in Japan. Waterways connected Hachiman and other cities to the lake, making it a strategic route for transporting goods from areas along the Sea of Japan all the way to Kyoto and Osaka Bay.

The Biwako Biennale’s main venue of Omihachiman bears the remnants of a bygone era when, in the late 16th century, Japan’s most famous warlord established his resplendent castle. A little while later and right up to the present day, the district thrived under the diligence and industry of an elite merchant group known as the Omi Merchants. Many of their houses still stand today. The biennale is distinctive in that many of these houses temporarily turn into galleries and museums for the event.

Nakata said: “Back in the early days of the biennale these merchant houses were empty and so were the streets. In 2004, there was only one cafe. Through the years, however, we convinced the owners of these houses to let us use them for the biennale and since then, they’ve been transformed into cafes, boutiques and guest houses. Now, people are coming in as well as inbound travelers who want to experience staying in an old Japanese house.” Thanks to Nakata and the biennale, there’s now a cycle of renovation, reuse and rejuvenation in Omihachiman.

The other venue is Okishima, an island in Lake Biwa. Okishima has a population of about 220, making it the only populated lake island in Japan.

“There’s a ferry to the island, but cars are not allowed,” Nakata noted. “The island is a gorgeous place, so rich in nature. At Okishima’s elementary school, we held a workshop with the students to create a mural, which will be on display at this year’s biennale.”

This year, the biennale will add a new venue. This is Chomeiji temple, part of the 33-temple Saigoku Kannon Pilgrimage and a work of art all its own. Erected in 619 on Mount Chomeiji, there are 808 stairs leading from the ground above the lakeshore to the temple, which offers panoramic views of both Lake Biwa and Omihachiman — a splendid launch point for the Biwako Biennale.

Chomeiji is also famed for its ties to Prince Shotoku, a revered regent and politician of the Asuka Period (538 to 710). Shotoku is said to have modernized government administration and endorsed diplomatic and trade relations with Asia, in particular mainland China.

“This year, we’ll be hosting our first exhibition by an artist from mainland China,” Nakata said. “Because of its relationship to Prince Shotoku, we felt that Chomeiji would be a wonderful setting for this work.”

Omi Merchants and Lake Biwa

In Japan, the Omi Merchants are revered as much for their modesty, discretion and self-discipline as they are for their wealth. Notably, many of the descendants of the original merchants have transformed their family businesses into prominent Japanese companies.

Behind the resounding success of the Omi Merchants is a particular business ethic called sanpo yoshi (win-win-win), meaning that a business transaction should benefit three parties: the seller, the buyer and society at large. Some business pundits say that sanpo yoshi is the original version of the United Nations sustainable development goals.

With such an estimable local heritage, it’s little wonder that Nakata chose Omihachiman to host the biennale.

“This is a city like no other. It’s as if you were transported back in time by about two and a half centuries.”

Though modern art exhibitions generally tend to be held in modern “white cube” structures, Japan’s regional art festivals have strong ties to their communities. At the biennale, each piece generates a reciprocal effect that highlights the historic streets and stately old houses of Omihachiman.

“The houses themselves speak of the Omi Merchants’ legacy — of their prosperity and admirable business ethics. They’ve become empty of residents but now the descendants of the owners are glad that the houses have been cleaned, overhauled and given new life.”

Art, lights and magic

This year there will be more than 200 works by 70 artists, and Nakata said that every one of them went through her personal selection process. “For every biennale I go abroad and make the rounds of art exhibitions, including student exhibitions in art schools and universities. The artist’s age, career history, notoriety — none of that matters. My only measure for selection is whether I love their work.”

In the early days of the Biwako Biennale, Nakata says many residents weren’t exactly receptive to the idea of an art festival springing up in their midst.

“They were apprehensive of what an art festival would be like, and of artists coming in from outside. They had a notion that artists were unusual people who would be hard to get along with. On the contrary, they were friendly and respectful of the locals and the environs. Now, everyone gets along. The other great news is that through the years, the children of Omihachiman got to grow up with the biennale. For them, art is a part of the Omihachiman streetscape and woven into the fabric of their daily lives.”

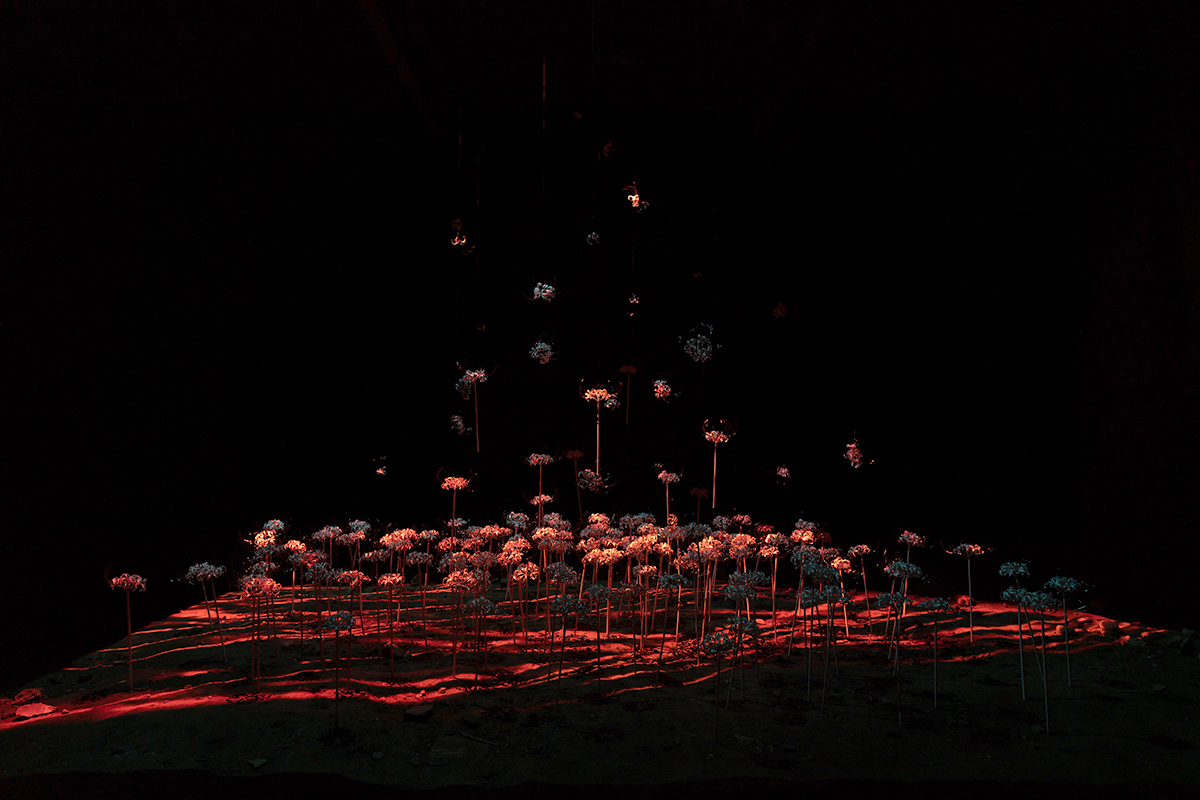

The same experience applies to the volunteers and interns that come in from all over Japan and abroad. “One of the staff member’s daughters is the artist saiho whose exhibit ‘Imagery Garden’ will be showing again this year.”

Lighting is another huge concern for Nakata, who emphasized the illumination of each exhibition represents the be-all, end-all of the biennale.

“People who come to Omihachiman will notice that these old historical houses were never wired for electricity,” she said. “Instead, they were designed to bring out the contrasting beauty of light and shadow. I think that the Japanese had a much more polished sense of aesthetics back when there was no technology. Now, sadly, our senses have become blunted and we just don’t have the same eye for beauty or the knack for noticing details that our ancestors had. This is why I put so much emphasis on lighting the exhibits. I want the buildings, the lighting and the exhibits to play off of each other and display hidden depths of beauty and allure.

“The biennale is not just about the art exhibits, it’s about the surroundings and the lighting, which I want to deploy as reminders of something evocative from long ago.”

“Every piece of art in the biennale is precious to me,” Nakata said.

The secret jewel

Despite that vision, moving the needle from zero to live art festival was harder than Nakata anticipated.

“I knew the venue of Omihachiman would work, but the logistics of securing the sites took some convincing,” she said. “The owners’ families had these buildings and houses for generations and perhaps they were apprehensive. But when they saw the actual biennale take place, they were glad they took the leap.”

“There used to be an ancient capital city in this prefecture, long before Kyoto. There are more temples here per capita than anywhere else in Japan. To hold an art festival here is so meaningful. The artists who come here all say they love the experience and some of them are repeat exhibitors,” she said.

Untouched by developers and excessive tourism, one can say that Omihachiman is one of Japan’s best-kept secrets, a jewel tucked away at the very back of the safe, as it were. “It’s an enchanted city. People who visit here keep coming back because there’s no way you can get enough from just one trip,” Nakata said.

“It is said that there are about 100 regional art festivals in Japan, but the Biwako Biennale is something special. The entire city of Omihachiman is a work of art and I hope that when people visit, they savor every moment.”

Yoko Nakata, general director of Biwako Biennale

Born in Otsu, Shiga Prefecture, Nakata lived in the U.S., the Philippines and France after graduating from Kwansei Gakuin University in 1980. After returning to Japan, she founded the Biwako Biennale international contemporary art festival in 2001.

International Art Festival

Biwako Biennale 2025

Exhibition period: Sept. 20 (Sat.) to Nov. 16 (Sun.)

Venues: Omihachiman Old Town, Chomeiji temple, Okishima island, Shiga Prefecture

Hours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. (Last admission: 4:30 p.m.)

Closed on Wednesdays (except Nov. 12)

For more information, visit: https://energyfield.org/biwakobiennale/