In 1966 and then again in '67, I spent from May to September in Cumberland Sound, a large inlet of the Labrador Sea on the coast of Baffin Island in Canada's far-northern Nunavut territory — a region the size of Western Europe.

At the time, as a marine mammal technician with the Montreal-based Arctic Biological Station of Canada's Fisheries Research Board, I was there to study seals and their relationship to the Inuit.

For those indigenous people, seals were — and still are — essential sources of food, fuel and clothing. Before Greenpeace and other conservationist groups started making loud and emotional protests in the 1970s against the annual killing of harp seal pups on the ice down south off Newfoundland and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Inuit hunters used to be able to make a decent living from selling seal skins.

Now, though, bans on seal skins in Europe and America have caused them serious hardship, and resentment runs deep about this in the Arctic.

Baffin Island, which is about 1.4 times the size of Japan, is the long island west of Greenland, and Cumberland Sound (Kangiqtualuk in the Inuktitut language) on its southeastern coast is around 250 km long and 50 km wide. With spectacular long, deep fjords and many islands, it is home to ringed, bearded, harp and hooded seals, as well as belugas and bowhead whales — while in high summer's brief open-water season, it is visited by marauding orcas.

I made my base in Pangnirtung, a remote hamlet of about 1,500 people from where I'd travel by dog sled, snowmobile or freighter canoe to the five remaining Inuit outpost camps. Until 1961, there had been a dozen such camps scattered through Cumberland Sound, but that year distemper killed off most of the dogs, making it well-nigh impossible to travel and hunt over the ice. Then in 1966, those new-fangled snowmobiles came in, decreasing the use of dogs even more.

Snowmobiles were fast and easy to use, but expensive — as was the imported gasoline they guzzled. Moreover, if yours broke down and you were stranded, you were in grave peril, meaning it was always wiser to travel in groups of more than one vehicle.

My job included moving around and hunting with the Inuit to take detailed data and samples from the seals we killed, as well as oral records from the hunters. I'd also have to remove the seals' lower jaws so that later, in the lab, we could age them from the growth of their large canine teeth.

At that stage in my life I had already been on five Arctic expeditions, and I'd also spent some 27 months in Japan and got married there.

I loved Japanese food and figured that a few Japanese touches to the way I ate raw seal, beluga and Arctic char would heighten my enjoyment, so I bought a large can of Kikkoman soy sauce from a Japanese store in Montreal and took it with me to Pangnirtung (a bottle could shatter if the liquid froze).

Dubious at first, my Inuit companions and their families tasted then really took to Kikkoman, and after that its use quickly spread. There were sweeter Chinese soy sauce brands sold at the Hudson's Bay Company store in Pangnirtung, but neither the Inuit nor I liked them. And so "Kikkoman" was soon part of the local language.

Now fast forward to July this year, when I had my 75th birthday aboard the Adventure Canada company-operated 12,900-ton cruise ship MS Ocean Endeavour at Kuujjuaq in northern Quebec — coincidentally, the start point of my first-ever Arctic expedition, in 1958.

From there, we sailed over to Baffin Island and then on to western Greenland on a voyage made exceptionally memorable by the company of Hidekazu Tojo — the oft-dubbed "Zen master of sushi" whose eponymous restaurant on West Broadway in Vancouver is renowned the world over.

I have known Tojo-san and his fabulous sushi for decades, and was looking forward to introducing him to my old friends in Pangnirtung, and to tasting sushi and other Japanese dishes made from local ingredients such as Arctic char, sculpins, turbot and Arctic cod — as well as fresh kelp, which is a traditional Inuit food.

Both Tojo-san and myself strongly felt that the Japanese way of preparing food could greatly enhance the rather unbalanced modern Inuit diet, which relies more and more on expensive junk food bought at the hamlet stores.

Back in the 19th century, flour, tea, sugar and molasses were taken there by whalers, and soon became integral parts of the Inuit diet. Then I introduced Kikkoman soy sauce ...

However, we were sure that if the Inuit could learn Japanese cooking methods, and then combine more ways to use traditional local ingredients, their nutrition could be hugely improved.

When I'd been in the Arctic before, I'd enjoyed raw and boiled seal, including the innards, as well as beluga, walrus, clams, caribou, hare, ptarmigan, ducks, geese and those fish I just mentioned — while fresh kelp dipped in hot seal broth was one of my favorite dishes.

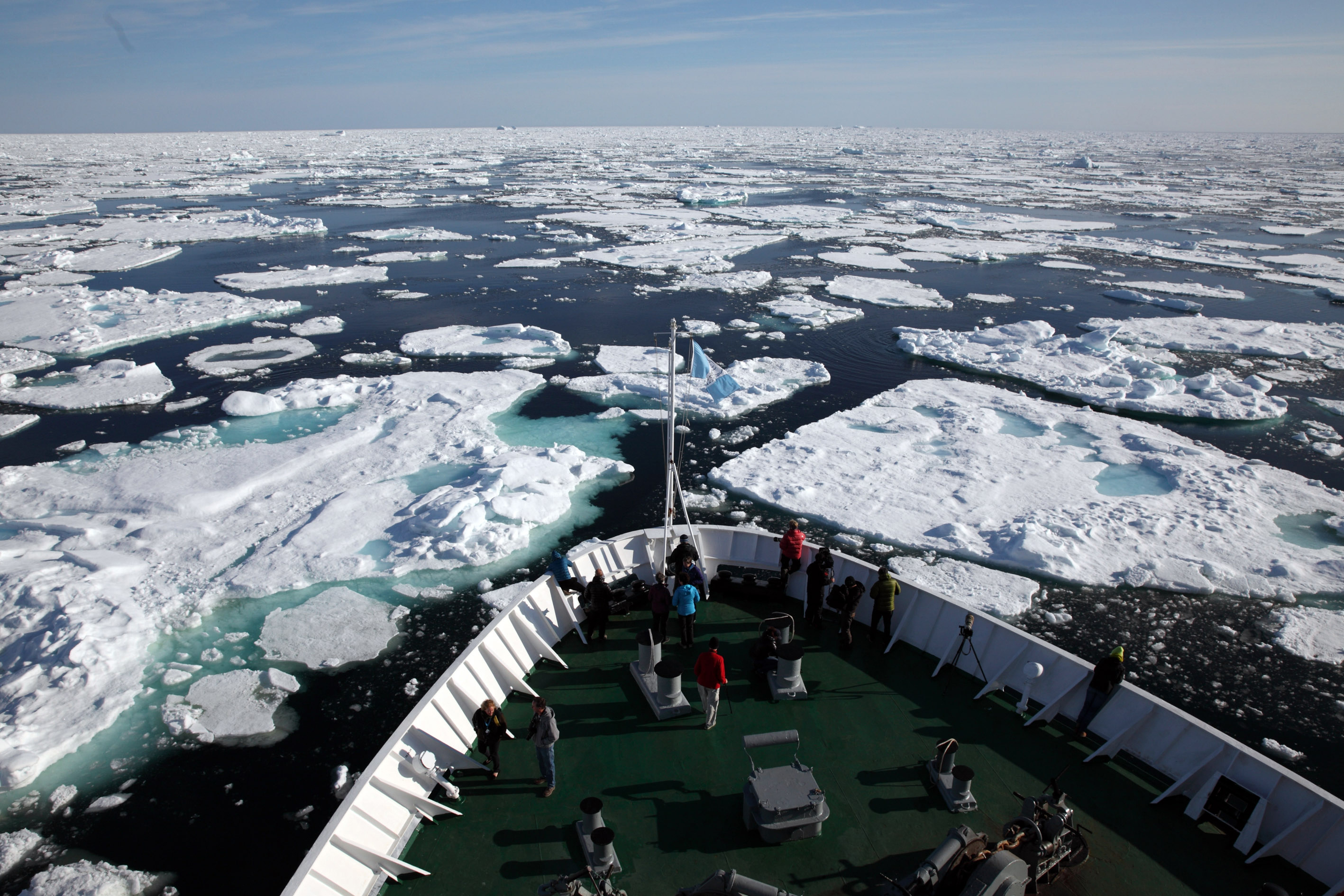

This year, heavy ice prevented us from getting into Cumberland Sound, but Tojo-san was able to acquire lots of Arctic char, a few sculpins and some Greenland prawns, and he held sushi workshops aboard ship for passengers and Inuit people invited from the hamlets we were able to visit.

It was no surprise to me that the Inuit loved Tojo-san's sushi, especially the famed California rolls he is credited with inventing after he moved from Japan to Vancouver in 1971. As a chef, he soon afterward realized that Canadians didn't much care for seaweed, so he turned the traditional maki-sushi (sushi roll) inside out to hide it — then the city's many visitors from California are said to have taken the idea home with them and co-opted the name.

Personally, I was disappointed that we didn't get Arctic turbot and more sculpins — the latter being small fish with big mouths and skinny tails that are traditional Inuit fare, though most other Canadians shun them.

Easy to catch, sculpins are very similar to scorpion fish, a great Japanese delicacy known as okoze that are eaten grilled, deep-fried whole or with the tail meat used for sashimi, sushi or tempura and the rest yielding a tasty stock.

As it happened, through the efforts of Aaju Peter, a lovely Inuit lady who sailed with us, Tojo-san managed to get a few sculpins, which he served deep-fried and whole. There was only enough for the Japanese and Inuit people aboard — and they were delicious!

It would be a culinary and cultural dream to return once more to the Arctic, and I would especially like to spend more time with Tojo in Pangnirtung. Who knows, we might start an Arctic food revolution!

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.