Back when Tokyo was Edo and Tokugawa shoguns ruled the land (1603-1867), the burgeoning city's most vital staple, rice, was protected in kura (storage houses) along the right bank of the Sumida River. Then, by the simple expedient of adding mae (in front of) to "kura," the area facing the white-washed, thick-walled granaries came to be known as Kuramae.

Eventually, the area morphed from grain sacks to become a center of box- and container-making, and I've heard that these days an influx of edgy designers is helping this corner of Taito Ward think outside the box. I go to explore.

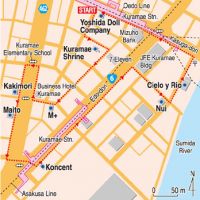

Exiting Kuramae Station on the Oedo Line, I slip down the first backstreet I see and find myself passing some worn little bars and a few small workshops where families still hand-assemble cardboard boxes — hardly what you'd term chic enterprises.

As I'm wondering if I've been misled, I stumble on Kuramae Shrine, a 1693 offshoot of Kyoto's Iwashimizu Hachimangu-ji shrine-cum-temple complex founded in 859.

Inside the shrine gate, a pert bronze sculpture of a dog stands on a pedestal that reads "Moto Inu." I ask the priest's wife, who is nearby trimming trees, if this was her dog. No, she laughs, explaining that "Moto Inu" is a rakugo (comic oral story) title. The tale, she informs me, concerns a white Hokkaido-inu named Shiro who is so beautiful that people often tell him he will surely be a human in his next life. Impatient, Shiro begs the shrine gods to transform him at once. His wish is granted, but the abrupt change renders him buck-naked and doesn't alter his canine nature. I can easily grasp the narrative's comic potential.

After I admire the shrine, the priest's wife calls me over to see a swallowtail caterpillar feasting on her Japanese pepper plant. "Let's scare him," she says, mischievously. I shrug, not sure how a caterpillar expresses alarm. She prods the little guy, and to my amazement, he unsheathes a set of tiny orange horns. Angered by a second prod, he rears up fiercely, and now those osmetaria emit a stink. Fearing further emissions, I thank the much-amused priest's wife, and move on.

Before long, I spy the subdued lighting and clean lines of just the sort of place I'm seeking. Shop M+ (pronounced "M Piu") actually smells heavenly of leather. Designer Yuichiro Murakami, 43, studied leather-working for several years in Italy (hence the piu, which means "plus" in Italian). From there he came to the capital's Taito Ward, where he spent two years at its Designer Village, a repurposed elementary school offering studio space to promising artisans and designers. Six years ago, Murakami finally opened his own Kuramae shop.

"I personally use each item I design, adjusting as I go," he says, unrolling a cow's worth of brown hide. "My next creation will be a pouch called Marsupio, which is Italian for marsupial." I admire his clever cardholders, wallets and crinkly, washed leather bags as I inquire about other designers in the hood. Murakami quickly reels off places I should go to see. Impressed, I ask him if he thinks Kuramae will turn into an exclusive designers' quarter.

"No," he says, "the balance is good right now. We don't want to lose the spirit of the place, and we don't want older residents and businesses to feel pushed out."

I carry this magnanimous idea with me as I thank Murakami and head off to explore the places he has recommended.

At a tiny tofu shop next door, I stop to purchase an irresistibly fresh-looking ¥100 cup of yose dofu (lightly pressed fresh curds). Realizing I'll be eating it on the hoof, the elderly shopowner plops a whole bottle of soy sauce into my bag. "Just bring it back when you're done," she says, exemplifying the local warmth Murakami is loath to lose.

Emerging on the major thoroughfare of Route 462, I easily locate a shop named Kakimori that is a mecca for those who love to write. Owner Takuma Hirose, 32, is the third generation of his family to run a stationery business, but the first to leave Gunma Prefecture for Tokyo.

"I opened Kakimori two years ago," he says, "because I wanted to offer something new, something neither mass-produced nor boring. Many customers know just what they want, and they treasure written communication. They know their inner feelings."

Hirose's shop swarms with young women whose inner feelings guide them through bespoke notebooks (from ¥1,000), made-to-order letterpress cards and mix-and-match envelopes with separate translucent liners. I sidle up to a display rack of Toshimasa Kawamura pens lathed from offcut remnants of rare woods and my inner feelings go berserk with lust. Getting a grip, I ask Hirose how he sources his unusual stock.

"It's worrisome, because many of the area's craftsmen are growing old," he says, holding a card handmade in the locality. "We need artisans who have successors, to guarantee continuity." To aid the essential cycle of supply and demand, I purchase several envelopes from Kakimori's bilingual staff member, Natsuko Toma, before heading on.

At my next stop, Maito, I enter a world of sublimely subtle hues in dyed goods. Owner Komuro Maito is another transplant to Tokyo, from Akizuki in the Kyushu prefecture of Fukuoka. "Akizuki is a great town for dyeing," he explains, "but not for selling." Maito, 29, is a second-generation dyer whose grandfather and nine prior generations were weavers. No surprise then that Maito, who has been learning the dyeing trade since he was 11, has a sensitive eye for fabric weaves as well.

Opened just weeks ago, Maito is still setting up, but soon he intends to hold dyeing workshops at which people will be able to learn how to coax delicate shades from natural colorants such as kaigaramushi (scale insects), akane (madder roots) and cherry-tree bark. Though most products he sells are dyed in Akizuki, where Maito's twin sister Sayaka and his father still run the family vats, he is eager to give traditional Japanese know-how a modern stage.

While hating to snip the thread of our conversation, I thank Maito and proceed to Edo-dori avenue. There, I find Koncent, a shop with massive glass doors and a name that is the Japanese word for "electrical outlet." Opened this April, this is the showcase for design projects from +D and H Concept, two companies built by Hideyoshi Nagoya.

"Nagoya was born near here," the PR person, Kayo Takahashi, tells me. "And he wanted to bring energy back to the neighborhood by selling locally the products he helps to develop."

She then explains how Nagoya collaborates with product-makers to add creative zing and design sense to their goods. For instance, for a company producing absorbent surfaces from naturally occurring diatomaceous earth, Nagoya developed a "bathmat" stone that instantly soaks up water from the feet. For a rubber-band company, he came up with bands in the shapes of animals, adding playfulness to the mundane needs of daily life. Though Koncent is surely one electrical outlet I've plugged into on my "cool shops" list, onward I once again must go.

Along the way, I've noted that Kuramae has many wholesale toy shops — but one in particular snags my attention with a tattooed 50-cm Kewpie doll. Cool beans, I think, asking the price. The shop-owner confides, with the promise of anonymity, that "Yakuza Kewpie" is ¥42,000 — wholesale. When I learn the doll has been inked by a real tattoo artist, it sort of makes sense.

Drawn toward the Sumida River, wondering if any storehouses remain there, I peek briefly into newly opened (and still mid-renovation) Guesthouse Nui, offering travelers ¥2,700 per night bunk beds, or a private double with river view for ¥6,500. The young staff and fresh feel to the place, plus the ground-floor bar, make it noteworthy. Likewise the vibe at nearby riverside cafe Cielo y Rio (literally, "Sky and River"), where a terrace table and their ¥850 salad plate are a salubrious delight.

At dusk, I head back to where I started. Once there, I can't resist a final stop. Sliding open the glass door to Yoshida Doll Co., I find an eerie display of countless sun-blanched Japanese dolls. I call out. The dolls stare. A clock ticks. Finally, from deep inside the shop, Seikichi Yoshida emerges. At 92 years young, he is spry and articulate about his work selling the fabrics and supplies used to make traditional Japanese dolls. As much as anyone I've met today, Yoshida convinces me that Kuramae's got great things in store.

"Sturm und Drang," an exhibition of photographs by Kit Nagamura, is open daily 0ct. 24-Nov. 24 from 10 a.m.-8 p.m. at Sin Den hair salon, 3-9-3 Jingumae, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo. Admission is free.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.