Along a winding path leading to the Jellyfish Pavilion at Expo 2025 in Osaka, Kansai, Japan stands a white arrow-shaped object. At first glance, it may seem to be just a stylish signpost. But if you look closely, touch it and rotate it, the arrow’s secret is revealed.

You would expect a left-pointing arrow, when turned 180 degrees, to point right. Yet this one stubbornly still faces left. If you rotate it slowly or view it from other angles, you will discover that it creates an optical illusion. Even after understanding how it works, if you return to your original viewpoint and rotate the arrow again, it will still seem to point left.

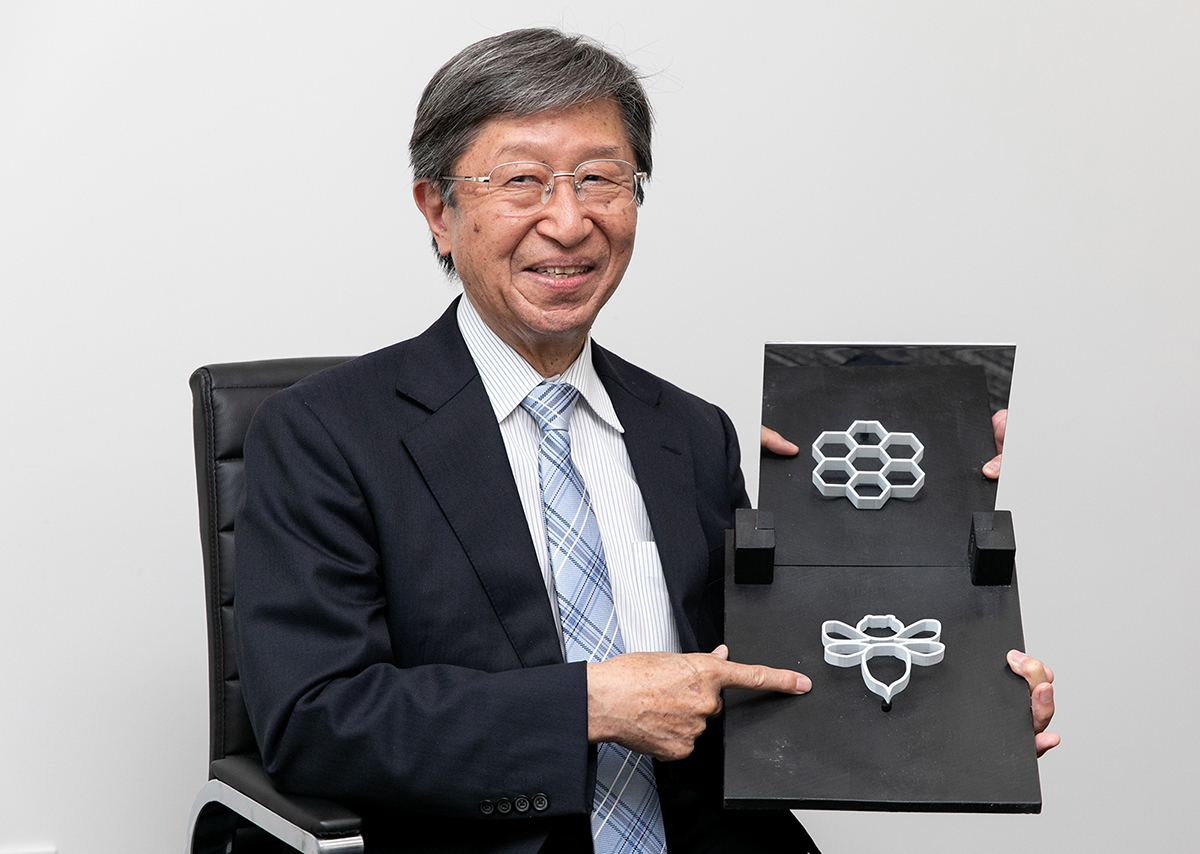

The creator of this object is Kokichi Sugihara, a distinguished professor emeritus at Meiji University’s Meiji Institute for Advanced Study of Mathematical Sciences (MIMS). Originally specializing in mathematical engineering, Sugihara’s academic interest in illusions stemmed from his early research on the functions of robots’ eyes during a computer vision project. Robot eyes are essentially cameras connected to computers that process image data, allowing the robots to make judgments about perceived events.

He became fascinated by the fact that humans, when observing the same thing, can sometimes experience illusions, leading to incorrect judgments, and began to use mathematical engineering as a tool to study human beings.

Analyzing the discrepancy between the result of robot data processing and what humans think they see has contributed to a deeper understanding of human visual perception. This enables predictions of how humans might misinterpret certain visual information.

“The human act of seeing and judging things with our eyes, and the illusions that we may experience during this process, have traditionally been the field of visual psychology. By introducing mathematics to study this topic, it became possible to predict how humans make judgments under certain conditions, leading to the discovery of new types of illusions and the creation of intended effects using illusions,” Sugihara said.

He explained that human brains do not accurately perceive depth when observing three-dimensional shapes. “We don’t truly understand the depth; we simply imagine it, and the imagination just happens to be correct most of the time,” he said.

Illusions likely occur when this imagination is incorrect, and since this imagination comes from the fundamental way we process information, it is largely consistent across individuals. This consistency allows for the systematic and mathematical creation of deceptive shapes when viewed from specific angles.

Sugihara said the next steps in his research will be to predict the stability of illusions through calculation. This involves defining the range of viewpoints from which illusions are consistently perceived for certain objects and creating objects that maintain their illusory effect regardless of the viewing angle.

He also said that accurately understanding why and what kind of illusions occur will help create living environments with fewer chances of illusions, thereby contributing to accident prevention and improved safety. “For example, it helps us alert drivers to the danger of illusions that make curves appear less sharp than they actually are,” he explained.

However, Sugihara is strongly against using illusions to deceive people for safety purposes, such as drawing illusory bumps on the road to motivate drivers to slow down. This is not only because the trick would only work once, but also because drivers accustomed to fake bumps might ignore real ones, leading to accidents. “I believe that no safety can be achieved by deceiving people with illusions,” he emphasized.

On the other hand, the mysterious and fun nature of illusions can be effectively used as entertainment or tourist attraction in safe environments. For instance, one of Sugihara’s projects involved creating snow slides at a ski resort where, from a certain perspective, sleds appear to defy gravity and slide upward.

In addition to his work as a researcher, Sugihara is also active as an optical illusion artist, but his approach to creating works differs completely from those of other sculptors. “For example, when I am making an object, I aim for it to look one way from a first perspective and entirely different from a second. These two distinct perspectives are expressed as equations, which a computer calculates and solves. If a solution exists, the shape is determined, eliminating the need for trial and error,” he explained.

While Sugihara admits that the artistic value of these works is still unknown, the fact that his pieces have been selected for various exhibitions suggests that his approach — using mathematical models as a new technique for artistic expression and production — is beginning to gain recognition. “However, art begins with an artist’s desire to express something and give it a form. Not everything an artist wishes to express can be represented by equations, of course,” he said. “Still, I feel that mathematics is well-suited as a method to create works that give viewers the sensation of witnessing something impossible.”

His works featuring stereoscopic illusions have been selected for the Nika Art Exhibition, one of Japan’s most renowned showcases for contemporary artists, for three consecutive years since 2022. His sculptures combine a 3D object and its unexpected “impossible” reflection in a mirror.

To allow people to experience stereoscopic illusions firsthand, MIMS, supported by Sugihara, held a workshop on May 8 at Expo 2025 showcasing some of his artworks, and paper kits for making stereoscopic illusions were distributed to visitors, helping them understand the principles of the phenomena.

There have also been collaborative projects between Sugihara and companies, integrating his works for promotional purposes and to enhance customer engagement.

His works are also contributing to international cultural exchange. In Hanoi, his solo exhibition “Optical Illusion,” organized by The Japan Foundation Center for Cultural Exchange in Vietnam, is running until Aug. 24, offering Vietnamese audiences an opportunity to observe and interact with illusions.

To share the enjoyment of illusions and explore their potential in contributing to society, Sugihara aims to continue his work at Meiji University on the topic across academic disciplines and beyond.

HP: https://www.meiji.ac.jp/cip/english/

Email: [email protected]