The G7 summit will take place from May 19 to 21 in Hiroshima — the first city in the world to have suffered the catastrophic consequences of a nuclear bomb during war.

Forty-three seconds after the atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima on an early August morning in 1945, the shockwaves from the explosion rolled through the city.

Tens of thousands died instantly, some vaporized in temperatures reaching 3,000 to 4,000 degrees Celsius. The blast ignited houses in the city center, followed by fires all over the city. Flames engulfed the area within 2 kilometers of ground zero, essentially melting everything and covering the area like lava. Trees were set afire, and utility poles and wood within about 3 kilometers were charred black. Hiroshima was instantly transformed into a hellscape for every living soul.

By the end of December, an estimated 140,000 of the approximately 350,000 people in the city had perished, including many visitors and commuters. Others not directly exposed to the blast later entered the city and were exposed to residual radiation, significantly amplifying the cruel effects of the bombing.

Miraculously, an aogiri (phoenix) tree in the courtyard of what was then the Hiroshima Communications Bureau building about 1.3 kilometers from ground zero still stood. Despite being directly exposed to the heat rays and the blast and apparently dead, it sprouted leaves the following spring, giving hope and courage to those in a state of collapse after their defeat in World War II.

The only structure still standing in that zone, the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, became colloquially known as the Atomic Bomb Dome in what is now known as Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

On Aug. 6, 1949 — four years to the day of the bombing — the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law was promulgated to develop the area as a symbol of permanent peace. Construction on Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park began in 1950 and was finished in 1955. The park and its structures were designed by Kenzo Tange, who won the 1987 Pritzker Architecture Prize.

The park is situated at the uppermost part of the delta where the former Ota River splits off from the Motoyasu River. The area was Hiroshima’s central shopping district from the Edo Period (1603 to 1868) until the early Showa Era (1926 to 1989). The park includes the Atomic Bomb Dome, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and numerous other monuments erected with fervent wishes for peace.

In May 1973, the phoenix tree was transplanted to the park. While some feared that it might die from being uprooted and moved, even now this symbol of survival against the odds flourishes and produces seeds. The latter are donated both domestically and internationally, and many second-generation trees are growing all over the world. It serves as a living metaphor for the regrowth and resilience of Hiroshima itself.

Vital regional hub

Nearly eight decades later, Hiroshima and its namesake prefecture have evolved into a prosperous manufacturing hub with a well-balanced group of industries ranging from heavy industries, such as shipbuilding, steel and automobiles, to cutting-edge sectors, such as electrical machinery and electronic parts. The city also boasts a concentration of government branch offices and corporate branch offices with jurisdiction over the Chugoku and Shikoku regions. Hiroshima has nearly 1.2 million residents now — around 3 1/2 times the population it had in 1945.

Tourism is a major facet of Hiroshima’s appeal. The number of visitors to the city exceeded 10 million for 15 consecutive years after 2005. From 2015 to 2019 — just before the pandemic hit — the annual number of foreign tourists exceeded 1 million, with 1.8 million overseas visitors in 2019.

The Atomic Bomb Dome, part of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996. The dome has remained virtually untouched since the blast, and serves as a sobering symbol of both destruction and the determination to bring peace to the world.

Naturally, Peace Memorial Park and other monuments to the past are some of the main draws here — as they should be — but they represent just one facet of the city’s identity. There is so much more to Hiroshima.

Crisscrossed by six rivers, Hiroshima’s nickname is the City of Water. Although the city has changed much over the years, it still maintains its personality and purpose. For example, streetcars from eight lines trundle through central Hiroshima. Remarkably, just three days after the bombing, some of the streetcars and sections of track had been restored. Three trams that survived the blast still run through the city. Two are in regular operation, while the third is used to help people learn about peace.

The prefecture and city also have diverse cultural and artistic resources that include multiple professional sports teams, the Hiroshima Symphony Orchestra, kagura (a traditional performing art that celebrates and expresses gratitude for the bounties of nature) and Itsukushima Shrine, a UNESCO World Heritage Site on the island of Itsukushima in Hiroshima Bay.

Hiroshima Prefecture also takes advantage of its diverse geography, from the cold northern highlands to the coastal islands, to grow a variety of agriculture products, including rice, vegetables and fruits. Hiroshima lemons are especially famous, and the prefecture is the No. 1 producer in Japan, growing well over half of the nation’s supply.

Hiroshima is also prime territory for raising livestock, and the prefecture is intent on beefing up its production base for prime wagyu and creating a brand name for itself to compete head to head with other regions producing the prized meat. That includes promoting the entry of more companies into the market, improving meat quality and fostering community corporations.

Nowhere better for peace

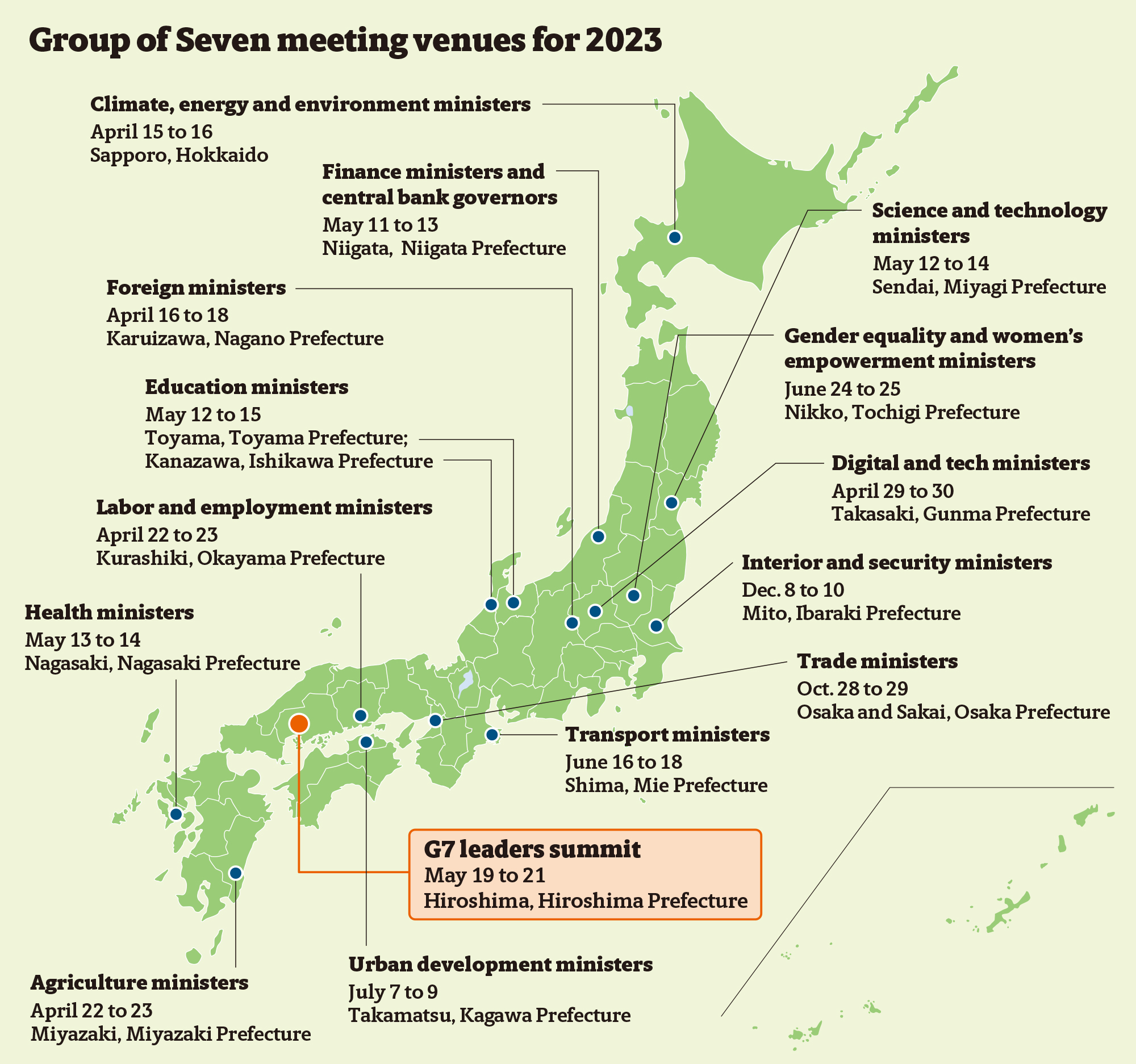

While Hiroshima is the centerpiece locale for the upcoming summit, ministerial meetings will take place throughout Japan. These venues will allow officials from the Group of Seven to confer on topics ranging from trade, science and technology, finance, gender equality, education, labor and employment to climate, energy and the environment (see map).

With roots in Hiroshima, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida began representing a constituency in the prefecture as a member of the House of Representatives in 1993. Thoroughly steeped in the city’s ethos of peace, he has been quoted as telling his G7 counterparts that “Hiroshima is best suited for the G7 to demonstrate its commitment to peace.”

Hiroshima’s people — together with the people of Nagasaki, which was also hit by an atomic bomb only three days later — embody the resilience of those who survived and eventually thrived again despite the devastation to their lives and land. The people of Hiroshima are following an initiative that began in 1995 on the tragedy’s 50th anniversary called Hiroshima 2045: City of Peace and Creativity, to create social infrastructures with superior design as the city moves through its next 50 years. They are also dedicated to creating an attractive urban environment that welcomes people from all over.

“I want to demonstrate to the world from there in Hiroshima the powerful commitment of the G7 leaders that the horror of nuclear weapons will never be repeated and that we resolutely reject armed aggression,” the prime minister said at a news conference in June.

Russia’s thinly veiled threats to use nuclear weapons since its invasion of Ukraine began have made such a commitment even more imperative. In his speech at the 10th Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in August 2022, the prime minister noted: “I cannot but admit that the path to a world without nuclear weapons has become even harder. Nevertheless, giving up is not an option. As a prime minister from Hiroshima, I believe that we must take every realistic measure towards a world without nuclear weapons step by step, however difficult the path may be.”

“Japan’s Transformation” is sponsored by the government of Japan.