A woody aroma fills the air at the Grand Shrines of Ise, Japan’s foremost Shinto shrine complex in Mie Prefecture. Towering hinoki cypress, at once heavy-scented and majestic, dot the landscape, an area measuring roughly 5,500 hectares and home to 125 shrines.

Of these, Kotaijingu Inner Shrine, or Naiku, dedicated to Amaterasu Omikami, the ancestral deity of the imperial family, is the most famous. The Oharaimachi street snaking to the shrine’s entrance and the offshoot Okage Yokocho street make for engaging strolls, with gabled storefronts harking back to the area’s merchant and oisemairi pilgrimage past.

But Toyouke Daijingu outer shrine, or Geku, dedicated to Toyouke, an agricultural goddess summoned from northern Kyoto Prefecture and enshrined at Ise about 1,500 years ago, provides rich insight into the significance of food and industry within Japan. Offerings of sacred food or shinsen — among them, salt, dried bonito, kelp and fish — have since been given to the deities twice a day.

Ocean’s value

The ocean’s rich bounty continues to play an important role in local industry today. Nowhere is this more pronounced than at Ise Shima’s Ago Bay. At Mikimoto Pearl Island, visitors can learn how innovators Kokichi Mikimoto, Tatsuhei Mise and Tokichi Nishikawa established processes for pearl cultivation, as well as attempt to extract pearls from farmed Akoya pearl oysters themselves.

Searching for pearls, however, can be traced back to the area’s ama free divers. Inextricably linked to Mie Prefecture, these women of the sea speak of over 3,000 years of fishing history, their practice depicted in ukioy-e and providing one of the first paid jobs for women in Japan. Many ama divers are reaching retirement and their numbers are dwindling, but their efforts help maintain the delicate balance of the marine ecosystem. A visit to a local amagoya hut such as Ama Hut Hachiman in Osatsu in Toba provides not only a fascinating glimpse into their lifestyles and disappearing practice, but also a chance to sample superbly fresh seafood grilled over charcoal flames, such as abalone, whelk and scallops on the shell.

Key Japanese ingredient

Yukiaki Tenpaku is a fourth-generation producer of katsuobushi, umami-rich, smoked and dried bonito skipjack that is used to make dashi, the cornerstone of Japanese cuisine.

Tenpaku’s business Maruten Co. is one of three remaining katsuobushi producers located at the windswept Nakiri Daiosaki headlands in Shima. Tenpaku offers tours to learn about the history of katsuobushi; these have proved popular with internationally famous chefs. Such is the quality and prestige of the firm’s nakiribushi bonito that it is offered to the gods at the autumnal Kannamesai harvest festival each year. The age-old tebiyama method of smoking and drying katsuo is practised within clay-walled huts, a process that takes up to a month to best preserve the fish. The wood used for smoking comes from felled Ise Jingu trees. Tenpaku acknowledges that bonito is used for dashi, while also noting its importance in the regional DNA and culture.

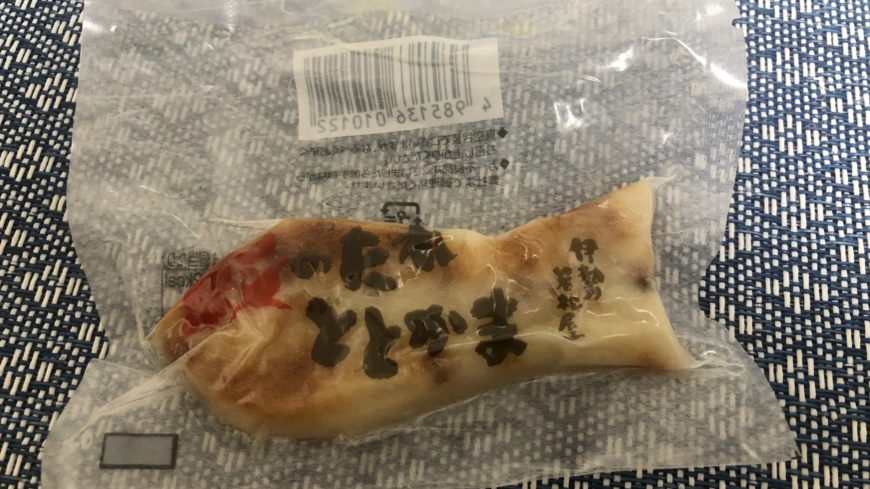

Kamaboko fishcake proprietor Wakamatsuya, located in the Kawasaki area in Ise and established in 1905, also adheres to long-held traditions in the making of its foodstuffs. Wakamatsuya’s ready-to-eat fishcakes are still made by hand and no artificial colorings, flavorings, or additives are used. Instead, white fish, salt and water form the nucleus of this age-old food. Visitors can participate in workshops to make their own kamaboko, where mashed fish is placed on a wooden board and broiled or steamed, as well as learn about area’s history when a fish market was in operation and Kawasaki gained its reputation as “Ise’s kitchen.”