U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation director James Comey designed his social media presence to be safe from prying eyes. He set up a private Instagram account only followed by family members, and subscribed to Twitter under a false name. After just one mention in a public speech, it took only a few hours of a reporter's time to discover the accounts with certainty approaching 100 percent. (Apparently in response to the story, the Twitter account — which quickly started gaining followers — is now available only to subscribers approved by its owner.)

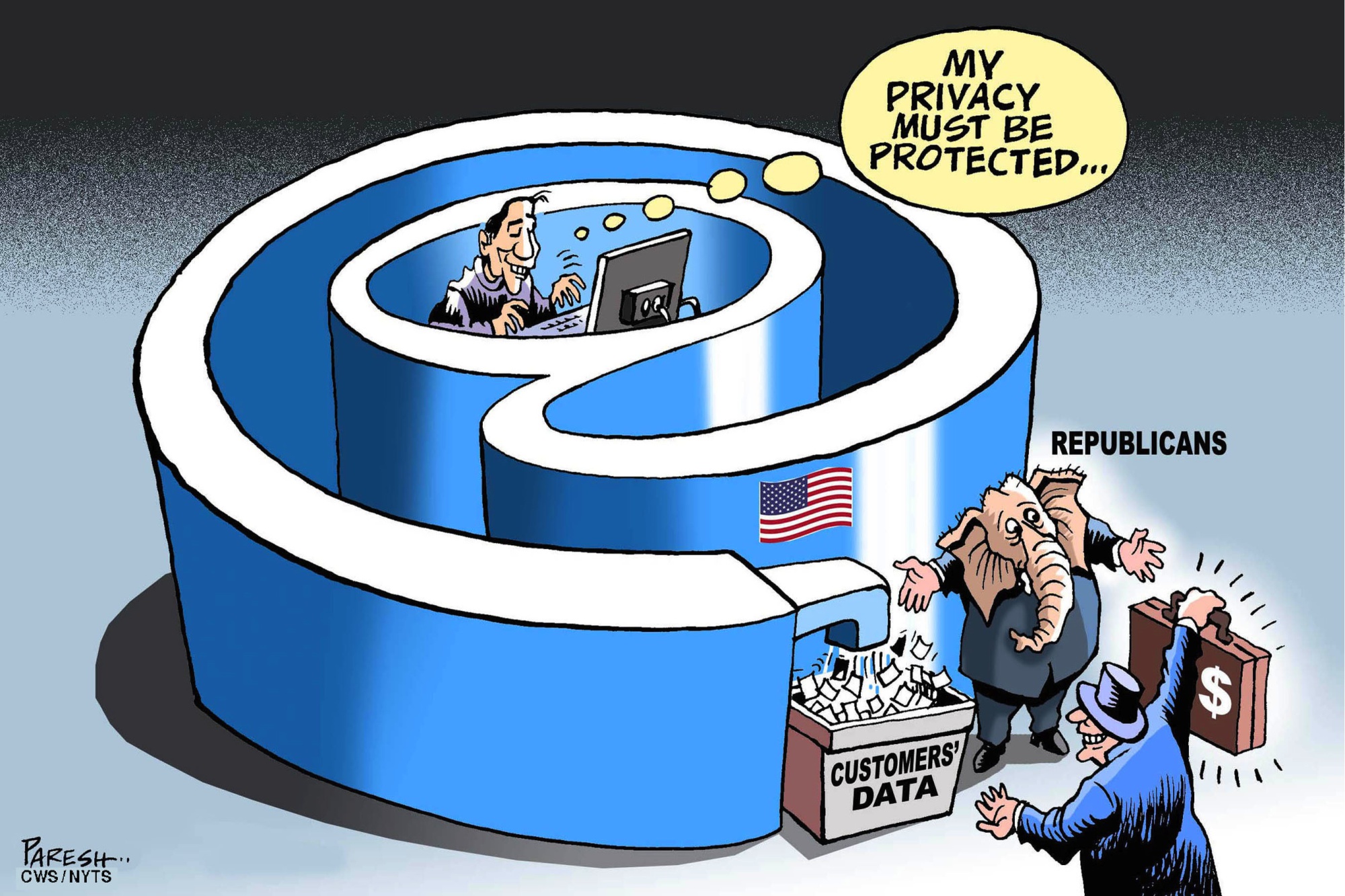

If anyone really wants Comey's family pictures and media-reading history, the Instagram and Twitter accounts will be hacked in no time. In any case, the companies involved have the data, and the Senate recently voted to allow internet service providers to sell personal browsing and app usage histories to advertisers — or, presumably, to anybody who wants them.

Meanwhile, the internet privacy of non-U.S. citizens is not protected at all thanks to an executive order that tells agencies foreigners are exempt from the U.S. Privacy Act, even though European officials cling to the illusion of an unenforceable "Privacy Shield" arrangement with the U.S. (Under it, affected Europeans are invited to sue in U.S. courts; I'd have to be officially accused of being the leader of ISIS before I'd contemplate that.) People the world over should be aware that using any of the services provided by major U.S.-based internet companies means giving up privacy altogether and opening up the most personal data to governments, advertisers, the press and private investigators. It also makes malicious hackers' work a lot easier because a lot of eggs are being put in large baskets.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.