If Japan, home to the world's largest public debt, wanted to save a bundle, it would close the Bank of Japan. Auctioning off its giant neo-baroque headquarter buildings around the nation and pink-slipping roughly 4,900 full-time employees would cheer Moody's and Standard & Poor's and plug holes in the national balance sheet.

That's not going to happen, of course. But imagine if the BOJ had closed shop 17 years ago, right after it first cut interest rates to zero, and turned its function over to a computer program. Would the artificial-intelligence version of the BOJ be any closer to 2 percent inflation than the well-compensated humans occupying its buildings? Probably not, seeing as how the BOJ remains on monetary autopilot programmed to up the stimulus at steady intervals.

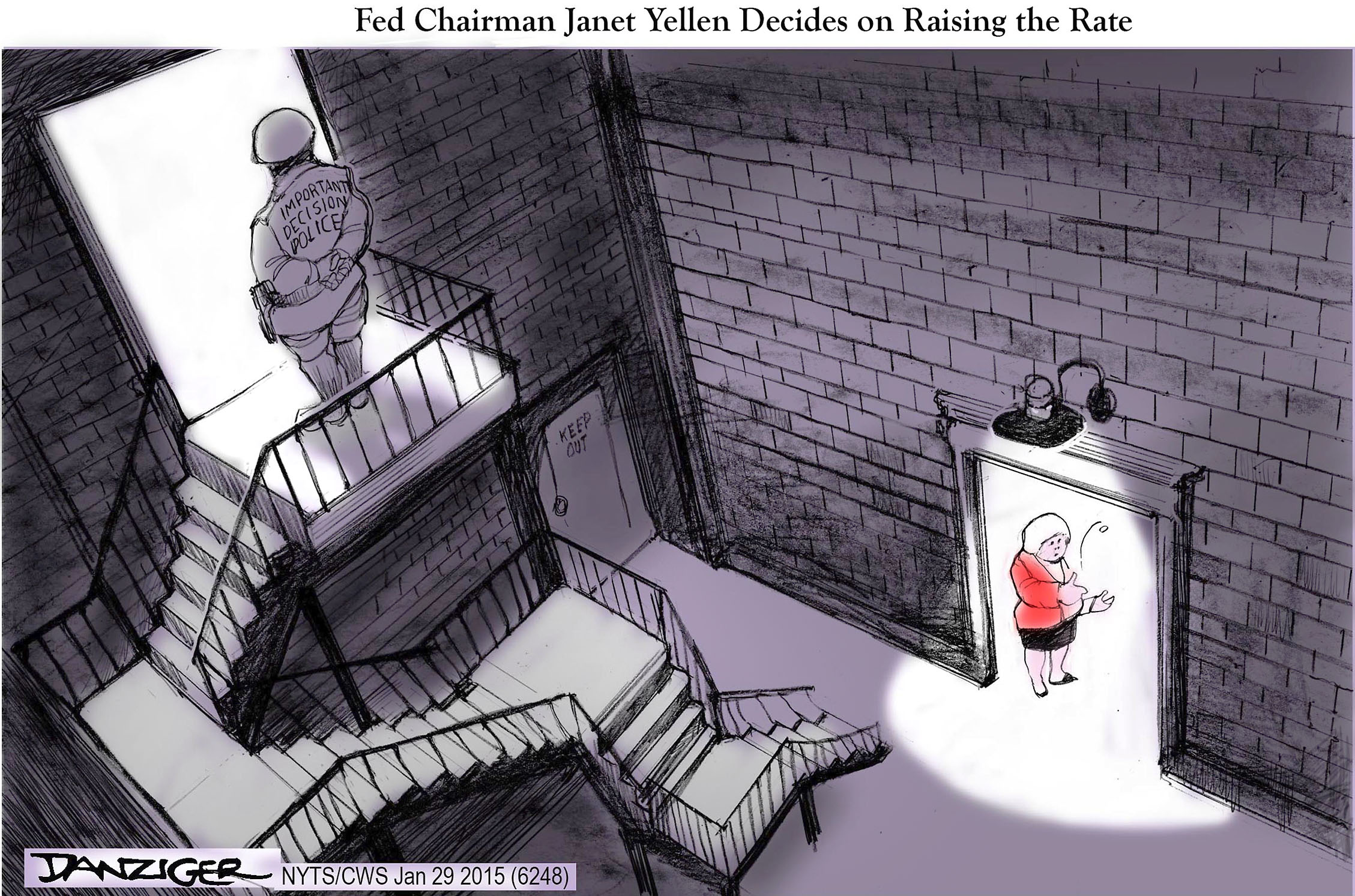

There's a cost to staying on automatic indefinitely, and one the BOJ's peers in Washington should be weighing carefully. Diminished credibility is one such cost. So is deadening the animal spirits and creative destruction that generate steady, healthy growth. But another is worth considering as both the BOJ and Federal Reserve approach pivotal rate decisions: confidence, and how policy generates it.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.