A few months ago, Jerry Izenberg, who has seen it all in his one-of-a-kind newspaper career, told me Muhammad Ali was once "one of my five best friends in the world."

At the time of the wide-ranging phone interview, Ali was 73 years old, and the 85-year-old Izenberg was remembering their unique friendship that spanned many decades.

But before Ali's death at age 74 on Friday, the iconic boxer and the legendary sports columnist hadn't been in close contact in recent years.

"The last time I spoke to Ali was about four years ago, when we could still communicate," Izenberg said in September 2015 by phone from his home near Las Vegas.

"But I'll tell you, we had a great relationship," he added.

What defined their relationship? I asked the 15-time Pulitzer Prize-nominated writer.

“I think the fact that, No. 1, he understood that I understood more about Islam than most writers,” Izenberg, the longtime Newark Star-Ledger sports columnist said. “And also about the Nation of Islam. . . . And I saw the metamorphosis in Ali . . .

"This is a guy who, until he lost his marbles, was . . . a devout Sunni Muslim. And I saw the transition from one thing to the other," Izenberg said.

Izenberg pointed out that the legendary boxer liked "familiar things and my face was always there.

"That's when we began to make this rapport."

"We could joke with each other about religion even," added Izenberg, who is Jewish. "I had a great respect for what he did and I never deified him."

On a PBS documentary, "The Trials of Muhammad Ali," released in 2014, Izenberg was asked to give his perspective on the former heavyweight champion.

"And I stand by the last thing I said, which they used to close the show," Izenberg said. "He wasn't a devil. He wasn't a saint. He just was Muhammad Ali, which was better than most people."

Their friendship was easygoing and was buoyed by talk — about practically anything.

"He would ask my opinion about things that he was really interested in," recalled Izenberg, who has covered all 50 Super Bowls and went to his 50th Kentucky Derby last month as a journalist.

"And we covered so many wives, so many countries. Gene Kilroy, who was the business manager in his camp, who was much closer than that — he was a friend — and Gene is white . . . and Gene and I were the two faces that were there all the time. All the time. And Jerry Lisker, who was the sports editor of the New York Post, God rest his soul, went with me to Ali's camp, I'll never forget it, just two weeks before Ali went to Africa for the Zaire fight (1974's Rumble in the Jungle against George Foreman)."

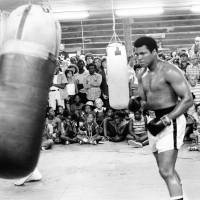

There, in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania, Izenberg and Lisker walked in on a training session.

"Ali's hitting the heavy bag and I said to Jerry, 'What the hell's going on?' Ali had arthritis in both hands, which people did not know," Izenberg said. "He had not been able to hit the heavy bag for a year and a half, and he looks over his shoulder and sees us . . . and he's banging the bag and he's saying, 'I'm gonna knock that sucker out. I'm gonna knock that sucker out. I'm gonna knock that sucker out.'

"And I say, 'You know something, Jerry? He's gonna do it.'

"I found out later how they healed his hand, and again I found that out from the guy who set it up and nobody else ever wrote it or knew it, and I don't even know if they knew he had bad hands because with (Dr. Ferdie) Pacheco always giving him shots and Novocaine, crap, and they were saying that this doctor took him off all that and did something else.

"Anyway, I picked him to win by knockout. There were probably 35-40 guys there, two of us picked him by knockout, and it was Jerry Lisker and me."

Izenberg, of course, will never forget that.

Once, while telling this story to another writer, Izenberg said, "Listen, just remember one thing: I remember the day he said to me a long, long time ago, 'If I say a mosquito can pull a plow, don't argue. Hitch him up.' And that's why I picked him."

Before the turn of the century, ESPN selected Michael Jordan as the greatest athlete of the 1900s. Babe Ruth was picked second, and Ali was chosen No. 3.

Izenberg disagreed.

"He (MJ) only impacted on the shoe industry," Izenberg commented, "and kids who are idolizing the fact that they are going to get the kind of shoes that he had. A great player? One of the greatest who ever lived. But the impact on the era was Ali.

"Nobody was neutral on Muhammad Ali. That's impact. And that's how I felt about him."

Izenberg went on: "I'll tell you how close we were. When he lit the torch for the (1996 Atlanta) Olympics, I called and he had a secretary called Kim out in Berrien Springs, Michigan. He bought (Al) Capone's old farm. I called her up that morning and I said, 'My paper's bothering me. Is he going to light the torch? I don't really care. But they want to know. I wanted to know for one reason: Whoever lit it was going to light it at night, and if it was him . . . how could this man be chosen?'

"Nothing else was gonna change, and I could make more papers, because you're always fighting a deadline."

"She said, 'Jerry, I don't even know if he's going to be there," Izenberg recalled. "He's had an asthma attack."

Talk about a fly in the ointment for a columnist on deadline.

"She's lying to me. OK," Izenberg said, "because of a non-disclosure thing."

Fast forward to the Opening Ceremony.

"So I look up and I see him and he's doing it," Izenberg said, "and I'm so f—- mad, because now I've got to work. I could've had an easy night, right?

"So the next morning I get a phone call — this is how our relationship is — (and) I'm staying at the Holiday Inn, which is about 15 miles (24 km) outside of town. I get a phone call and this voice says, 'Fooled you, didn't I?'

"And I said, 'Who is this?' I know who it was, of course.

"Muhammad."

"And I said, 'Muhammad who?'

"He said, 'Muhammad Ali, the greatest of all time.'

"I said, 'The Muhammad Ali who told me he never tells a lie because he can't go to paradise if he does. That Muhammad Ali?'

"What are you talking about?"

"Well, Kim said you were in the hospital," Izenberg replied.

"He said, 'Well, Kim ain't no Muslim. She can lie.'

"And then he says, 'Come over here.'

"Where are you?"

Ali informed his friend he didn't know where he was. So his wife, Lonnie, got on the phone. She told Izenberg to stop by the Omni Hotel.

"We were registered under such-and-such a name," Izenberg recalled Lonnie Ali saying. "Come up, knock on the door and we'll let you in."

He arrived at the hotel.

A while later, the two old friends were alone. Ali lay down on the bed to rest and they began talking.

"Now," Izenberg said, "you can still understand him but you've got to a) know who he is; and b) if you know him, get accustomed to his voice. It always takes you a while to readjust. And he's going to say about five words, and you are going to have to translate that into a full paragraph.

"And he's talking to me and he's talking about the closet, and I think he's saying someone's in the closet. I didn't know what the hell he sees, and he's mumbling, so I go and open it up. In the closet is the Olympic torch.

“I bring it back and I hand it to him. He looks at me and he puts it in my hands because he thinks he’s doing a great thing . . . because he thinks it’s a great thing for me to hold the torch. So I thanked him and I handed the torch back and put it back in the closet.

"And he shows me he burned his arm lighting the torch. Nobody knew that."

Seeing the Opening Ceremony on TV — because of the vast size of the Olympic Stadium — Izenberg recalled seeing "sweat coming down his face, and it was hot. But I realize what it is; you know, when he would go to fights at that point, he'd put his hands in his pockets to hide the tremor. . . But he had no pockets in his sweats . . . So he's got his left arm pressed against his body so hard, trying not to shake. And in that concentration, he burned his arm. But he told me about it."

Indeed, the special bond between Izenberg and Ali extended beyond their jobs. It was truly unique.

"I'll tell you how close our relationship was," Izenberg said without hesitation. And his razor-sharp memory set the stage for a series of unforgettable moments that go beyond the typical encounters between journalists and pro athletes.

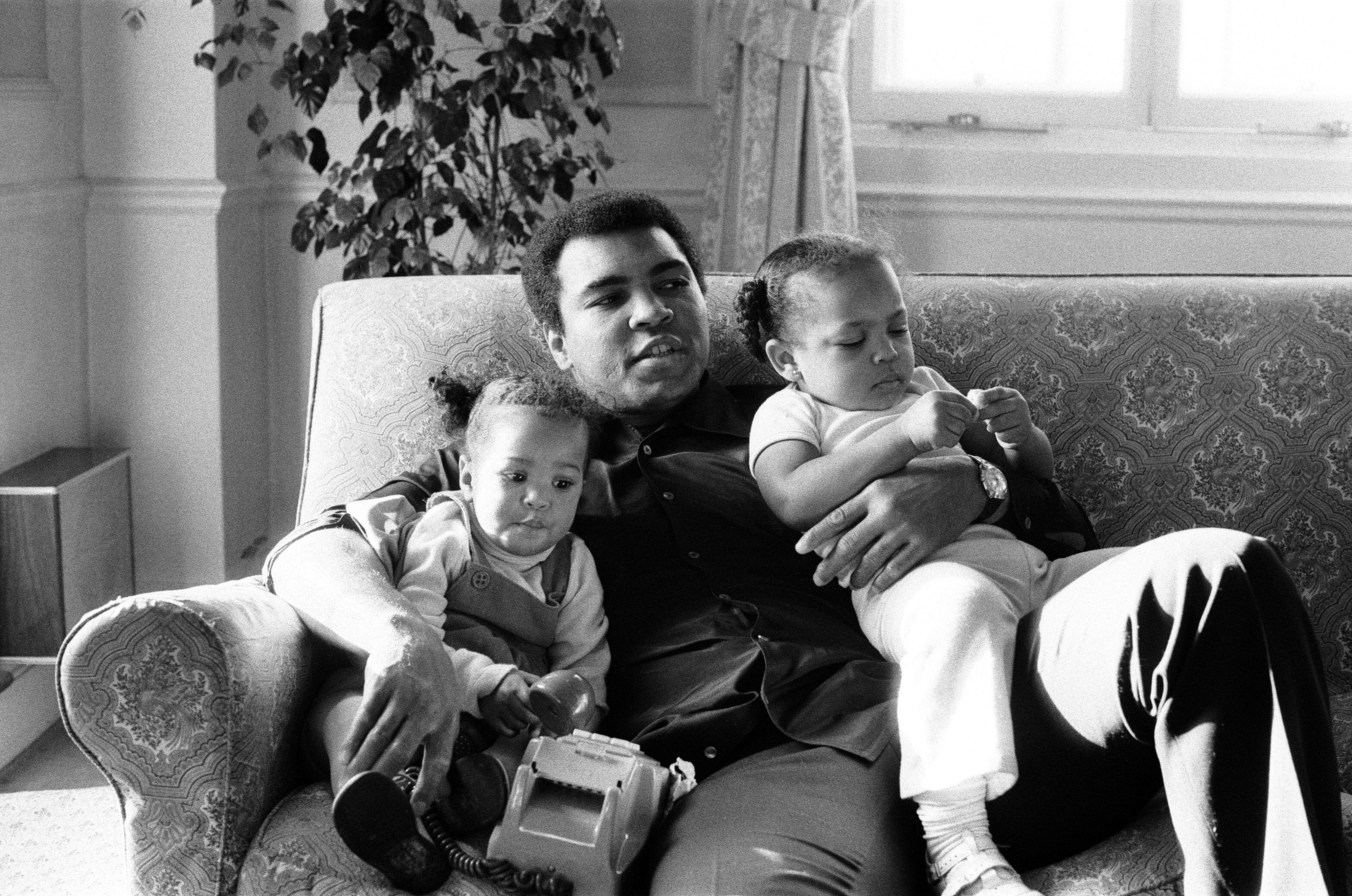

It's 1974, and Izenberg was a recently divorced father. (He said that at the time he was the first father in New Jersey to be awarded sole custody of his children.)

He's doing work in preparation for Ali's fight in Kinshasa, Zaire, against then-world heavyweight champion George Foreman — The Rumble in the Jungle, Oct. 30, 1974.

While children, Robert, 11, and Jenny, 8, had just come to live with him two days prior, his parental instincts were put to the test.

"I'm driving to Deer Lake (Pennsylvania), and I've got my daughter and my son in the car," recalled Izenberg.

It was a challenging set of circumstances. Izenberg had plenty of work to do. In his heyday, he wrote five columns a week. (And that's not all. He wrote books and magazines articles. And over the years, he was involved in the narration, production and writing of 35 TV documentaries, among them the Emmy Award-nominated "A Man Named Lombardi.")

At any rate, en route to Deer Lake, Izenberg was confronted with figuring out how to keep his children occupied while he is covering Ali's training camp.

"He is crazy about television and I'm making a television show at the same time," he remembered about his son, and gave him these instructions: "You can walk around with the crew; they know who you are. Don't worry about it.' "

One down, one to go.

"His (daughter) says, 'What am I gonna do?' " Izenberg recalled.

His orders? "Well, you go to Aunt Coretta (Ali's aunt) and tell her that you are the official water girl of the Jerry Izenberg television crew and she'll give you a couple of bottles of water and you follow them around with, but you keep your mouth shut.

"Then she proceeds to say, 'I hope George Foreman knocks his block off.'

"I said, 'What are you talking about?'

"I said, 'You've got to remember something: Both of these men are my friends, No. 1. This is a business, No. 2. It's not a war, so they'll do what they do to make their money. And you are going to keep your freakin' mouth shut when you get in there.'

That set the stage for the TV cameras to start rolling.

"So they go off and do what they do and we do the show," Izenberg said, "and now we are in his locker room and we are talking very softly, and he says to me, 'Is that your son?' He didn't know he hadn't seen him."

Ali asked Izenberg what his son's name was, then walked over to him.

"He put his arm around Robert and says, 'Robert, I want to tell you something. You have come to live with a great man who loves you. Learn from him.' And he gets up and walks away," Izenberg remembered.

"Well that's a helluva thing to do for me," he went on. "The kids have been scared. They came to live with me two days earlier. . ."

The conversation continued.

"So is this your daughter here?" The Greatest inquired in a quiet tone.

"When you're 7 years old, 8 years old, tell me what you think we're talking about. She thinks I'm ratting her out about what she said about him," Izenberg pointed out.

"So she's trying to put her shoulders into the molecules in the wall, right? Because she thinks I'm ratting her out."

As Izenberg remembered it, Ali said, "Little girl, will you come up here please."

"Little girl, I'm talking to you . . . You come up here right now!"

Izenberg’s daughter walked over to them slowly, and then . . .

"He swoops down, and he's 6-3 (190.5 cm), and she wasn't even 5 feet (152 cm) then," the legendary sports columnist said. "He picks her up and holds her over his head. Now she has lost the total power of English. She cannot speak one word that means anything."

The conversation shifted back to Ali.

"Is that your daddy?" he asked her.

She mumbled.

"Is that your daddy?"

She mumbled again.

"Don't you lie to me, little girl," the boxer said. "Don't you lie to me. That man is ugly. You're beautiful. He's not your daddy. The Gypsies musta brung you. Now give me a kiss right here (he points to his cheek)."

As they're driving home in Izenberg's car, boxing talk between him and his daughter resumed.

“She says to me, ‘I hope Muhammad can win the fight.’ "