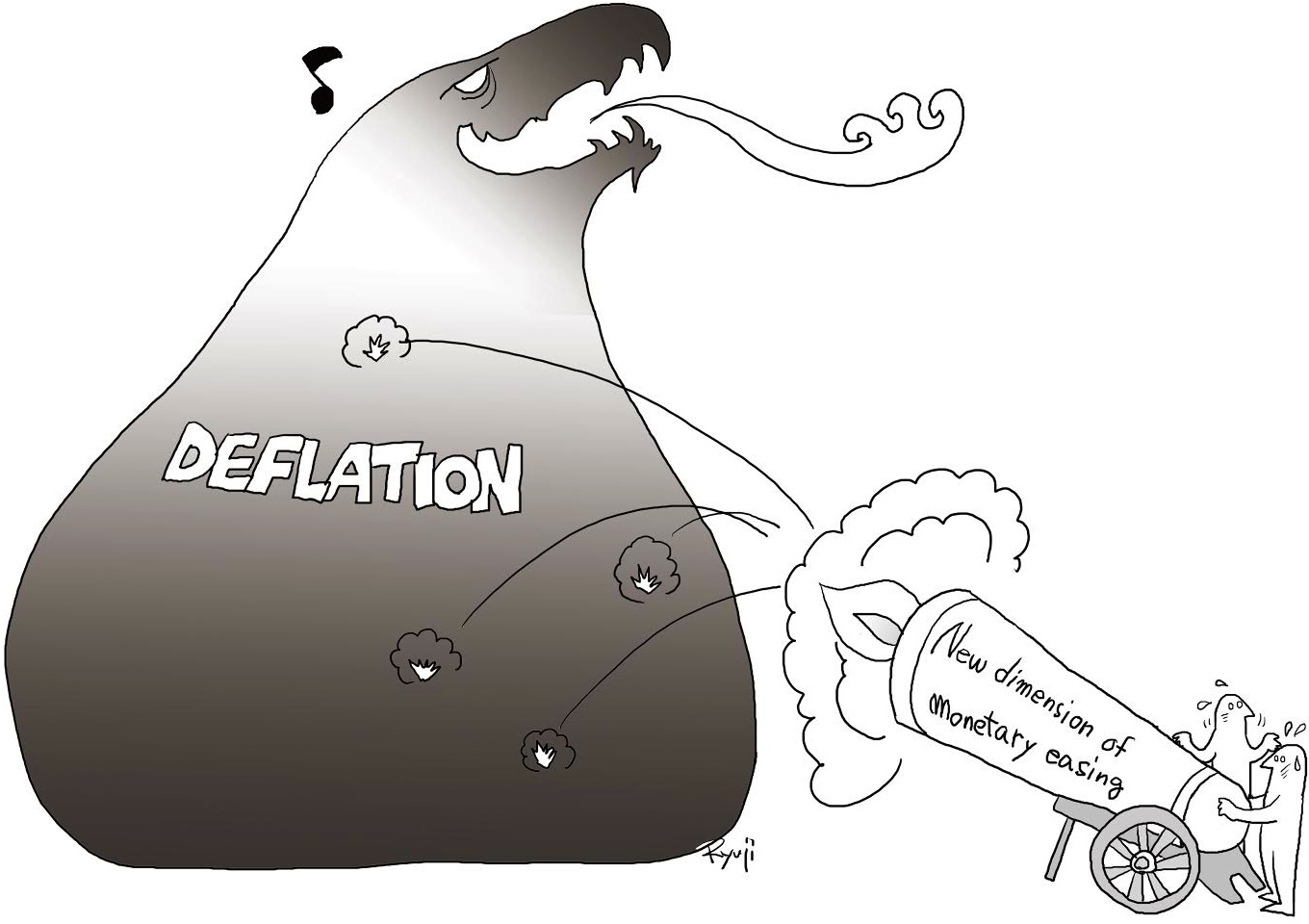

For four years, the Bank of Japan has pursued monetary easing of unprecedented dimensions — both qualitatively and quantitatively. It is common knowledge that the policy has had no effect for its intended task of ending deflation in this country. There may be a long list of excuses for the failure, such as the fall in crude oil prices, slowdowns in emerging economic powers, and the impact of the 2014 consumption tax hike.

But it is now time for economists to accept that the simple macroeconomic view — which theorizes, by comparing a highly matured economy like Japan to a machine, that you can freely control the output of the economy such as prices, household spending and capital investments by private-sector businesses by adjusting the input like monetary and fiscal policies — no longer works. In other words, it must not be overlooked that the Japanese economy today has undergone qualitative changes from the early 1980s, when fiscal and monetary policies worked effectively.

Had household spending, housing purchases or capital investments been sluggish because interest rates were too high — and prices falling because of a shrinking monetary base — the BOJ's "unprecedented" monetary easing since 2013 would have swiftly achieved its target of a 2 percent annual inflation and triggered a dramatic increase in domestic demand. In short, the grand social experiment over the past four years has refuted the hypothesis that deflation is a monetary phenomenon. It has become increasingly safe to assume, therefore, that deflation is caused by a gap between supply and demand in the real economy.