In his Tokyo Shimbun column about weekly magazines, Hiroyuki Shinoda recently lauded Shukan Asahi for accusing Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of exploiting the murder of journalist Kenji Goto by the Islamic State group for political purposes. Shinoda points out that the magazine had been intimidated by the "bashing" its associated newspaper, the Asahi Shimbun, received last summer after the latter retracted a series of stories about the "comfort women." So he was relieved when he saw that Shukan Asahi had recovered the "true essence" of the weeklies' job, which is to make trouble for those in power.

Regardless of Shukan Asahi's intentions, the real job of the weeklies is to make money. Though they have a reputation for pestering public figures, their primary reason for doing so is to sell magazines. The mainstream media is too beholden to government and the business world to act as effective watchdogs, so it falls to the weeklies and tabloids to rake whatever muck there is. There's nothing inherently wrong with trying to earn profits through journalism, but in the weeklies' case coverage decisions are dictated by which stories will shift the most units.

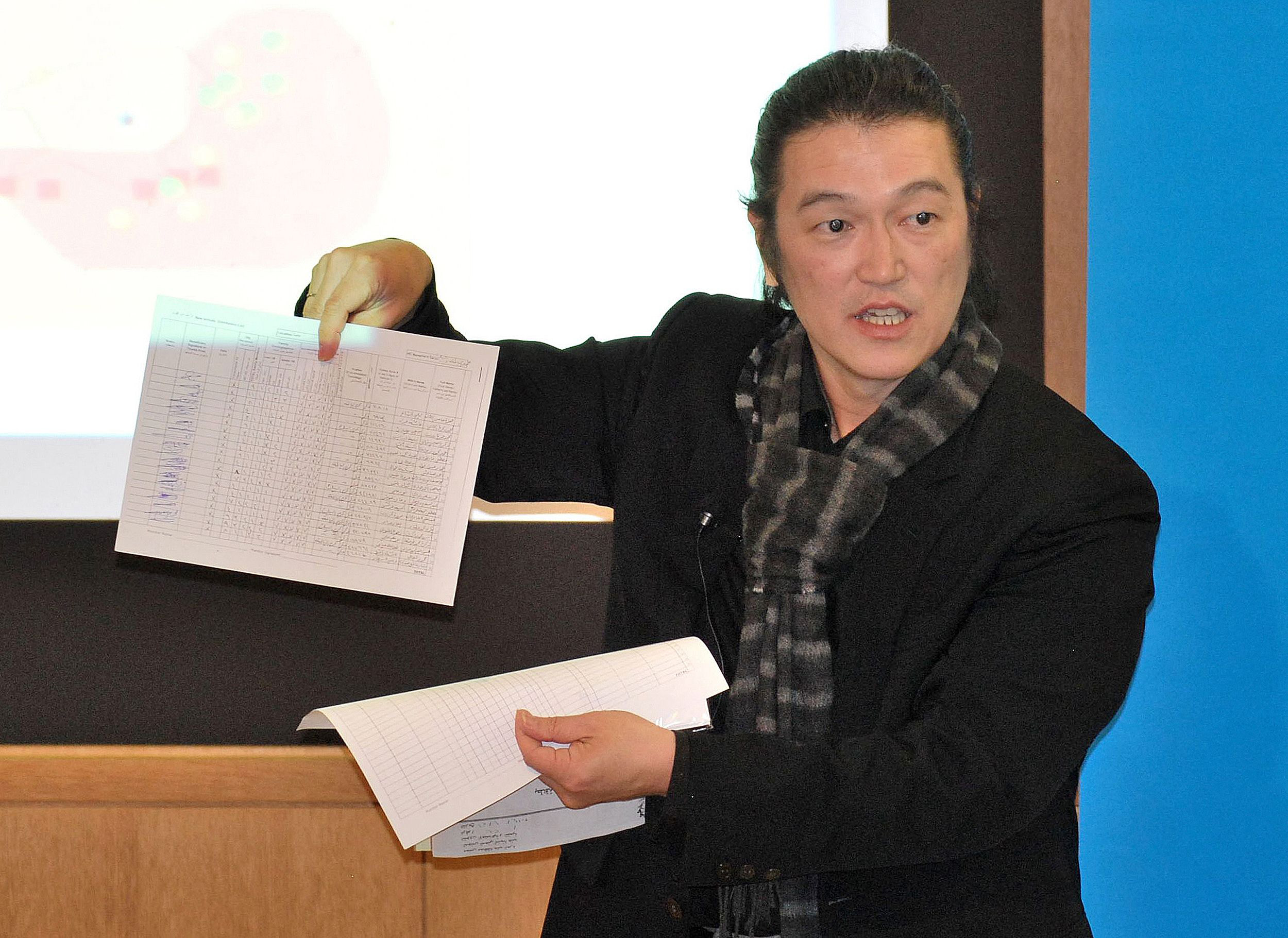

Documentary filmmaker Tatsuya Mori elaborated on this idea in an essay he wrote for the Feb. 11 edition of the Asahi Shimbun. Mori is put off by the official stance the administration and, in turn, the media have assumed when talking about the deaths of Goto and another Japanese hostage, Haruna Yukawa. The government, always prefacing its remarks on the matter with a reference to the despicable nature of their killers, insisted it would never negotiate with terrorists, thus creating an atmosphere in which anyone who questioned its handling of the matter was seen to be on the side of "evil."