The next time you trek out to the Tokyo Regional Immigration Bureau, situated on the fringes of Shinagawa along Tokyo Bay, look around and you'll see a giant smokestack by the Konan Ohashi Bridge. The visa-dispensing center, essential for foreign nationals who want to live in Tokyo, stands right by a garbage factory. However, the Minato Incineration Plant plays a key role in efforts to promote sustainable living in the capital: It houses a state-of-the-art recycling plant.

Every week, thousands of plastic crates are placed along the streets of Tokyo to collect recyclable materials. In offices, supermarkets, train stations and other facilities throughout the capital, recyclable bottles, cans and other materials are meticulously separated and placed in the appropriate receptacles. In Minato Ward, for instance, glass jars and bottles are placed in yellow crates, while cans and tins are deposited in blue crates. Minato crews collect these as well as newspapers, magazines, cartons, cardboard, recyclable plastic and plastic bottles. Everything except paper is trucked down to the Minato Resource Recycle Center, which is located on an artificial island across the Keihin Canal from Shinagawa. Opened in 1999, the three-story building showcases technology that can help reduce the environmental impact of modern consumer lifestyles.

Bales by the truckload

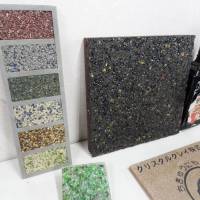

Crates full of glass containers are placed on conveyor belts and rolled up to the plant's second floor, where machinery takes over. The line automatically tips the crates over, spilling the bottles and jars onto another belt, where workers remove any unsuitable items. Those that make the grade are shaken as they move along the belt to increase the distance between them. A lighting and camera system then automatically scans and sorts them according to glass color (clear, brown or other), and small pneumatic actuators, like mini catapults, tap them so they jump off the belt and fall into the appropriate chute, falling to the first floor, where the impact helps break them up. The line can handle 1 ton per hour, or roughly 4,000 bottles. The shards are collected by recycling companies and made into road paving material or bottles once again.

The factory floor here thrums with workers, trucks and forklifts. Aside from glass smashing, the plant's activities are mainly focused on compacting, crushing and washing. Cans and tins make their way through a sorting machine that uses magnets to separate steel and aluminum, compressing 1,400 cans at a time. The result are compact bales of multicolored, twisted metal weighing 20 to 50 kilograms that would look perfect in a contemporary art exhibition. The metal is remade into cans, auto parts or construction materials.

Plastic bottles made of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a common polyester resin, are scooped up in a wheel loader and dumped into a bin at the bottom of a compactor, which can ingest half a ton of bottles per hour. They come out the other end as 17-kilogram bales, about 40 centimeters a side, that hold the equivalent of 300 1.5-liter bottles. After processing, the PET can be used to make new bottles, fabrics and stationery goods such as Pilot's Petball, a ballpoint pen that even looks like a PET bottle.

By far the heaviest bales made at the Minato plant are fashioned from recyclable plastics such as food packaging, bento trays, shampoo bottles and cup noodle containers — or, indeed, anything else with the "Pla Mark." This material is also put on conveyor belts, blown with a high-pressure fan to remove plastic shopping bags, sorted by workers, and finally put through a giant compacting machine and bundled into 280-kilogram bales measuring 1 square meter and wrapped in white vinyl. The line can process 2 tons of plastic per hour. The bales are then shipped to companies that turn them into new plastic products or chemical resources.

"We hope that more people will thoroughly separate their garbage and recyclable plastics such as food containers, so we can improve the recycling rate," says Akihiro Naito, a manager at the plant.

Few of Tokyo's 23 wards have a recycling plant such as Minato; most rely on private companies to process recyclables. In addition, the type of recyclable material varies by ward — Minato gathers plastic containers for recycling but Setagaya Ward, Tokyo's most populous, does not. Recycling companies are just one of many players in the recycling game that also includes individuals who illicitly gather recyclables from plastic boxes put out by wards. One such collector operating in Setagaya, shouldering an enormous bag of scavenged aluminum cans, said he gets ¥130 per kilogram.

"Minato Ward currently recycles about 29.8 percent of its recyclable materials and the current goal is 42 percent by 2021," says Ko Taguchi, a manager in Minato's garbage reduction division. "Some 26 percent of burnable garbage and 12 percent of nonburnable garbage can be recycled, so we're trying to raise awareness of that by working with citizens and businesses."

The '3R' strategy

Japan uses around 200 million kiloliters of crude oil annually. The vast majority is refined into gasoline, kerosene and other forms of oil and burned as thermal energy; about 2.7 percent goes toward making plastic.

Recycling is a massive industry in Tokyo. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government says it is promoting the "3R" strategy of reducing, reusing and recycling resources. According to the metropolitan government's Bureau of Environment, Tokyo in fiscal 2014 recycled a total of nearly 112,000 tons of glass containers, 45,055 tons of PET bottles, 15,473 aluminum cans and containers, 564 tons of paper packaging, 114,897 tons of corrugated cardboard, and 10,740 tons of black and white food trays.

It may be hard to believe that the 3R approach is making much headway when ubiquitous drinks vending machines, plastic grocery bags, disposable chopsticks and food packaged in multiple layers of plastic, such as plastic packages of individually plastic wrapped cookies, remain the norm in Tokyo and the rest of Japan. Some 60 percent of Japan's household waste by volume is made up of food packaging and other plastic containers.

Plastic is also a significant source of ocean pollution. In a recent study of remote, uninhabited Henderson Island in the South Pacific, researchers from Britain and Australia found that Japan and China were leading countries of origin for the 17 tons of plastic waste that has floated there.

If you believe data produced by the industry, however, things are improving. In 2015, domestic consumption of plastic products was down 1.3 percent to 9,640,000 tons, while general plastic waste fell 1.7 percent to 4,350,000 tons, according to numbers from the Plastic Waste Management Institute, a group financed by manufacturers including polyvinyl chloride maker Shin-Etsu Chemical, Japan's largest chemical company. It says the overall plastic recycling rate has improved from 46 percent in 2000 to 83 percent in 2015.

"Plastic has become an indispensable material for everyday lives, not only in Japan but overseas as well, as seen even in polymer bank notes," says Plastic Waste Management Institute Manager Hitoshi Tomita, a former plastics engineer. "The Lehman shock of 2008 and the 2011 earthquake are some factors that have led to reduced production of plastic resin."

Recycling can have positive effects on the environment. According to the Council for PET Bottle Recycling, carbon dioxide emissions associated with PET bottles in fiscal 2014 were 50 percent less than they would have been if recycling processes were not used; the energy savings were about 40 percent.

In the bigger picture, however, Japan is a recycling laggard. According to 2014 data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the municipal recycling rate for Japan was only 21 percent, below top-ranked Germany at 48 percent, Sweden at 33 percent and the United States at 26 percent.

"From an academic or technical point of view, 100 percent recycling is strange and isn't realistic," says Kunihiko Takeda, an outspoken recycling critic and professor at Chubu University's Institute of Science and Technology Research who has written books with titles such as "We Should Not Recycle!" "As such, it's a very difficult question as to whether Japan's recycling rate is appropriate. I think that it's reasonable for recycling to happen without government subsidies."

The 1997 Containers and Packaging Recycling Act calls for consumers, industry and government to cooperate in recycling and reusing plastic resources. But while the recycling method for PET bottles via mechanical means is long-established, new chemical methods have been developed. Meanwhile, there's no standard for dealing with the many other types of plastics we use and discard every day, but chemical processes are opening up some possibilities.

Chemical rebirth

There's a scene in "Shin Godzilla," the latest installment in Toho's long-running monster franchise, that features the titular monster towering over an industrial landscape in Kawasaki. The Showa Denko factory in the foreground, a riot of pipes and silos that traces its history back to 1930, features a unique plastic recycling facility that opened in 2003 at a cost of ¥7.4 billion. The chemical maker, which also recycles around 5 million aluminum cans annually, generating about 80 tons of aluminum, says its heat gasification process can recycle plastics such as food packaging with zero emissions and total recycling of all byproducts.

Showa Denko's heat gasification process is a form of chemical recycling, which breaks down materials into their constituent parts. Derived from petroleum, plastic is a compound made up of carbon and hydrogen in long molecular chains known as polymers. Heat can break those chains and dissolve the plastic into elementary gases.

The process begins when bales of waste plastic are put through a crusher machine, which pulverizes them before another machine removes foreign objects such as metal, which is recycled. The plastic begins to resemble a gray, gooey pulp, which is poured into a forming machine that then shapes the pulp into cylinders called refuse plastic fuel. The refuse plastic fuel is moved to a gasification plant where it enters two towering furnaces. In the first, a vortex of sand heated to between 600 and 800 degrees Celsius instantly turns the refuse plastic fuel into a gas, leaving any metallic materials to accumulate at the bottom of the furnace for recovery and recycling.

The gas is then shunted to an even hotter furnace silo where it swirls around while being oxidized at 1,400 degrees Celsius with the help of oxygen and steam. This produces a synthesis gas made up in large part of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, while a quick cooling stage that chills the gas below 200 degrees Celsius prevents dioxin resynthesis. The gas then undergoes several cleaning stages, removing hydrogen chloride and sulfur while converting the carbon monoxide into hydrogen and carbon dioxide. The hydrogen is piped to an adjacent Showa Denko plant where it's turned into ammonia, used in everything from acrylic fiber to medication, while the carbon dioxide goes to a CO2 plant that produces the fizz in carbonated drinks. Operating around the clock and known among industry otaku (geeks) for its nighttime lights, the plant has more than 1,000 workers and can process 195 tons of waste plastic a day, producing 175 tons of ammonia.

"The CO2 in carbonated drinks you consume may have come from plastic recycled here, but plastic has no taste," says Toru Takeda, head of chemical recycling promotion at the plant. "Meanwhile, the ammonia in some anti-itch medication you may be using could have come from here. Showa Denko is the only company in the world with this ammonia production technology."

PET project

PET bottles debuted in Japan in 1977 as soy sauce containers that were colored green and marketed as shatterproof, lightweight, disposable and more convenient than glass bottles. Later, the plastic was made transparent for easier recycling and PET bottles have since become the industry standard.

Some 563,000 tons of PET bottles were sold in fiscal 2015 and 501,000 tons were collected, according to the Council for PET Bottle Recycling, which estimates an 86.9 percent recycling rate.

"As a raw material for food containers, the PET obtained from mechanical recycling is superior to chemical recycling in terms of cost effectiveness and a reduced environmental burden," says Takashi Nakamura, an executive at the council. "In chemical recycling, the PET resin obtained by repolymerization is treated the same as the virgin PET resin in terms of quality because it's decomposed into a monomer and purified at the molecular level."

Down the road from Showa Denko's gas plant is another mountain of piping representing another method of dealing with waste plastic. As its name implies, the PET Refine Technology plant in Ogimachi specializes in PET bottles.

Opened in 2008 under major packaging and PET bottle maker Toyo Seikan, it makes 23,000 tons of polyester resin annually by processing 27,500 tons of used PET bottles, mostly from the Kanto region centering on Tokyo. Bales of PET bottles are stacked in a yard and graded according to how clean they are, and whether caps and labels have been removed; the residue liquids emit an almost palpable pong.

"We want consumers to be aware of the importance of removing all residue liquids from bottles as well as the caps and labels before recycling," says Toshiko Ito, an assistant manager at the plant.

After being loaded onto conveyor belts, they're screened for foreign materials, washed and pulverized, and the resulting flakes are put through a complex depolymerization and purification process that produces purified bis-hydroxyethyl terephtalate monomer (BHET), an organic compound used to make PET.

The final step is called polymerization — that is, making new polymers, the long molecular chains of monomers, the building blocks that form plastics. The BHET goes through a melt and solid phase polymerization process that produces PET flakes that can then be turned into new PET bottles or higher value-added products such as anti-corrosive PET film for aluminum drink cans made by Toyo Seikan. In 2016, the company's technical prowess won a Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry Award for Resources Recirculation Technologies and Systems. One challenge is the low price of PET flakes.

"This is the only place the world where BHET can be extracted from waste PET bottles," says PET Refine Technology President Sei Ishii. "Unfortunately we can't sell all we produce because of market conditions, but we're hoping for more demand in the future."