Japanese gardens are often associated with temples, feudal estates or castles. Genkyu-en in Shiga Prefecture is certainly no exception, sited as it is adjoining a detached palace in the grounds of Hikone Castle, one of only a handful of the nation's feudal fortresses to have survived in its original form.

The two-hectare stroll garden was completed in 1677 on the orders of the provincial lord, Ii Nao-oki. The garden was named after the Tang Dynasty detached palace of the Chinese emperor Hsuan Tsung (685-762).

Essentially a circulation garden, it is also termed a chisen-kaiyu (landscape style), the name indicating a design centered around a pond. Located to the east of the castle, the garden borders its inner moat, where white lotuses bloom in summer.

If Genkyu-en's assertive rock settings hint at the strong martial aesthetic of the Momoyama Period (1573-1603), the garden's expansive pond fed by water from nearby Lake Biwa, and notable for its set of four islands based on the Isles of the Immortals in Chinese mythology, speaks more strongly of design tastes associated with the early part of the succeeding Edo Period (1603-1867).

A fondness for narrative elements in gardens of this period is evident in the way rocks are implanted into the landscape. One stone arrangement represents "Eight Views of the Omi Area" (on the Sea of Japan coast of present-day Niigata Prefecture); while a further grouping stands for the white rocks of the Oki Islands in the Sea of Japan, which are now in Shimane Prefecture.

Contrasting with the predilections of domain lords and the garden designers working under them, and highlighting the duality that is often a feature of Japanese arts, are Genkyu-en's teahouses and pavilions, cantilevered above the shoreline of the pond. These structures speak of different tastes and preferences, of a connoisseurship in Japanese aesthetics and the tea ceremony.

Hikone Castle has been inducted into the garden as a key visual feature. This technique of appropriating scenery, natural features, and even suitable man-made structures into the confines of gardens, has been practiced since the Heian Period (794-1185).

The expression used to describe this method, shakkei (lit. borrowed view) appears for the first time in China at the beginning of the 17th-century. In his widely read and adapted work, "Yuan ye" ("Manual of Garden Design"), the Chinese painter and garden designer Ji Cheng, wrote then that "skill in landscape design is shown in the ability to 'follow' the lie of the land and 'borrow from' the existing scenery."

Two centuries later, Kyoto gardeners were heard using the term ikedori (lit. capturing alive) to describe the same process. By enticing a distant view of nature or enhancing external structures into the garden, a skillful designer creates an art composition, one that expands existing space by manipulating depth of field.

A place of beauty and a testing ground for various style canons, the garden was also conceived of as a place of entertainment and diversion for guests. This is readily apparent in many an Edo Period print and painting, notably the "Genkyu-en zu" ("Genkyu Garden View"), in which nobles and other guests can be seen from the perspective of a teahouse as they float on the pond in opulently painted sailing boats.

Teahouses are usually placed in well-appointed locations, often presenting the finest view of a garden. Hosho-dai, a teahouse with period lampshades and red carpeting covering parts of its tatami areas, was named to express the Taoist idea of a commanding height from which the Chinese phoenix soars into the sky — hence Hosho-dai translates as, "the phoenix's landing place."

Certainly it's well worth sampling a bowl of steaming-hot matcha (green tea) at Hosho-dai, at least for its view of the garden framed by pillars, a verandah and eaves.

Oddly enough, another of Genkyu-en's notable qualities is that it is not overly maintained or manicured, with tufts of grass growing on its embankments and last autumn's dry leaves blown into the root cradles of trees.

Similarly, though supremely elegant within, its thatched buildings have a mildly ramshackle aspect, suggesting that little change has been wrought on the garden over the years.

A pair of stereoviews taken of Genkyu-en in 1898, one monochrome, the other a more costly tinted version, show two carefully coiffured young women, dressed in kimono and holding oiled umbrellas, standing on a timber bridge with the outline of the castle in the distance. The images were the work of Nobukuni Enami (1859-1929), a gifted photographer who ran a highly successful studio in Yokohama. The first person in Japan to use 3-D negatives as the production base for producing lantern-slides, he returned countless times to Genkyu-en to exploit its pictorial setting.

Today, however, the astonishing thing about looking at Enami's images is realizing how little the garden has changed to this day. Not only has the integrity of the garden been preserved, but also its environs, which remain apparently identical to a century ago.

The lack of modern structures and other distractions around this quietly sequestered garden ensures a rare peace and repose.

Visitors who stay long enough may hear the venerable time-keeping bell, struck every three hours, of Hikone Castle. In summer and early autumn, the unruly chirping of cicadas and crickets adds to a soundtrack that was set in motion many, many centuries ago.

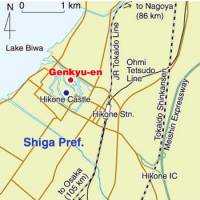

Getting there: Genkyu-en Garden is a 15-min. walk from Hikone Station on the JR Tokaido Line, making it easily accessed from Kyoto or Osaka. The garden is open daily from 8:30 a.m.- 5 p.m. The admission fee of ¥600 includes entrance to Hikone Castle. Green tea, priced at ¥500, is served from 9 a.m.-4 p.m.