It is not easy to regard oneself as an oppressor.

While Japanese enjoyed unprecedented prosperity in recent decades, residents of Okinawa have endured a burden others simply do not appreciate, says photographer Ari Hatsuzawa, who has published a pictorial study of what he calls the complex reality in Okinawa.

The book, titled "Okinawa no Koto wo Oshiete Kudasai" (Let us Know About Okinawa) published in August, features colorful, sometimes humorous photos of everyday life in Okinawa. But its underlying message is clear: People outside the prefecture must learn more about the complicated issues its residents face.

"Onaga stated the problem as an ethnic minority issue at the United Nations," Hatsuzawa said during a recent interview with The Japan Times. He was referring to a speech by Gov. Takeshi Onaga on Sept. 21 at a session of the U.N. Human Rights Council in Geneva, in which he said Okinawa's right to self-determination and human rights have been neglected.

"The fact that Okinawa, representing 0.6 percent of Japan's territory, shoulders 74 percent of the U.S. forces' facilities clearly shows the structural discrimination by Japanese people against Okinawa," said Hatsuzawa, 42, who spent 15 months in the prefecture from November 2013 on a photography project.

He said it is thanks to Okinawa, burdened with U.S. bases, rather than to Article 9 of the Constitution that Japanese people have been able to enjoy 70 years of postwar safety and economic prosperity.

"This is an inconvenient truth that Japanese people don't want to face," he added.

Hatsuzawa, who majored in sociology at Sophia University in Tokyo, said he tries to approach those who have been neglected with the understanding that he is among those responsible. When taking photos, he tries to capture ordinary everyday life, scenes that are often overlooked by outsiders.

This approach is also apparent in his earlier works, including books of photos of people in Iraq, North Korea and disaster-hit Tohoku.

Despite choosing such locations, Hatsuzawa insists he is not a photojournalist.

"Journalists focus on injustice, but what I address as a photographer is absurdity — which includes myself," Hatsuzawa said.

"I wanted to learn about the real Okinawa, which I did not understand by reading news," he said. "But the complicated reality was beyond my understanding."

In his book, Hatsuzawa admits he had difficulty understanding Okinawans' mixed emotions toward U.S. bases and tourists from mainland Japan, both the target of antagonism but both also regarded as financially indispensable to the prefecture's survival.

During his stay, he drove around Okinawa Island by motorbike and photographed a wide range of subjects, from traditional ceremonies and seasonal festivities to young people on the streets, U.S. bases and soldiers, and biracial children and families.

Hatsuzawa also tried to meet local people and talk, hopping bars night after night. But conversations were not easy.

"Okinawa people do not easily speak their minds. And maybe, I sometimes unconsciously spoke in a way as if I knew all about Okinawa," he said.

"One night at a bar, a man said to me, 'rather than taking back photos you took, why don't you take back one of these bases?' " Hatsuzawa said. "I could not reply."

This was one of the moments when he was reminded of the fact that he had entered the land of the oppressed, as one of the oppressors.

Hatsuzawa's photos often include multiple elements. For example, in a photo taken at a cafe in Chatan, three young women are dressed in boldly designed kimono for a coming-of-age ceremony. They are standing by a table under a red parasol, while a smiling young woman in jeans with her boyfriend from a U.S. base sit at the next table.

"Because that's the reality of the world. It's multifactorial and disorganized," Hatsuzawa said.

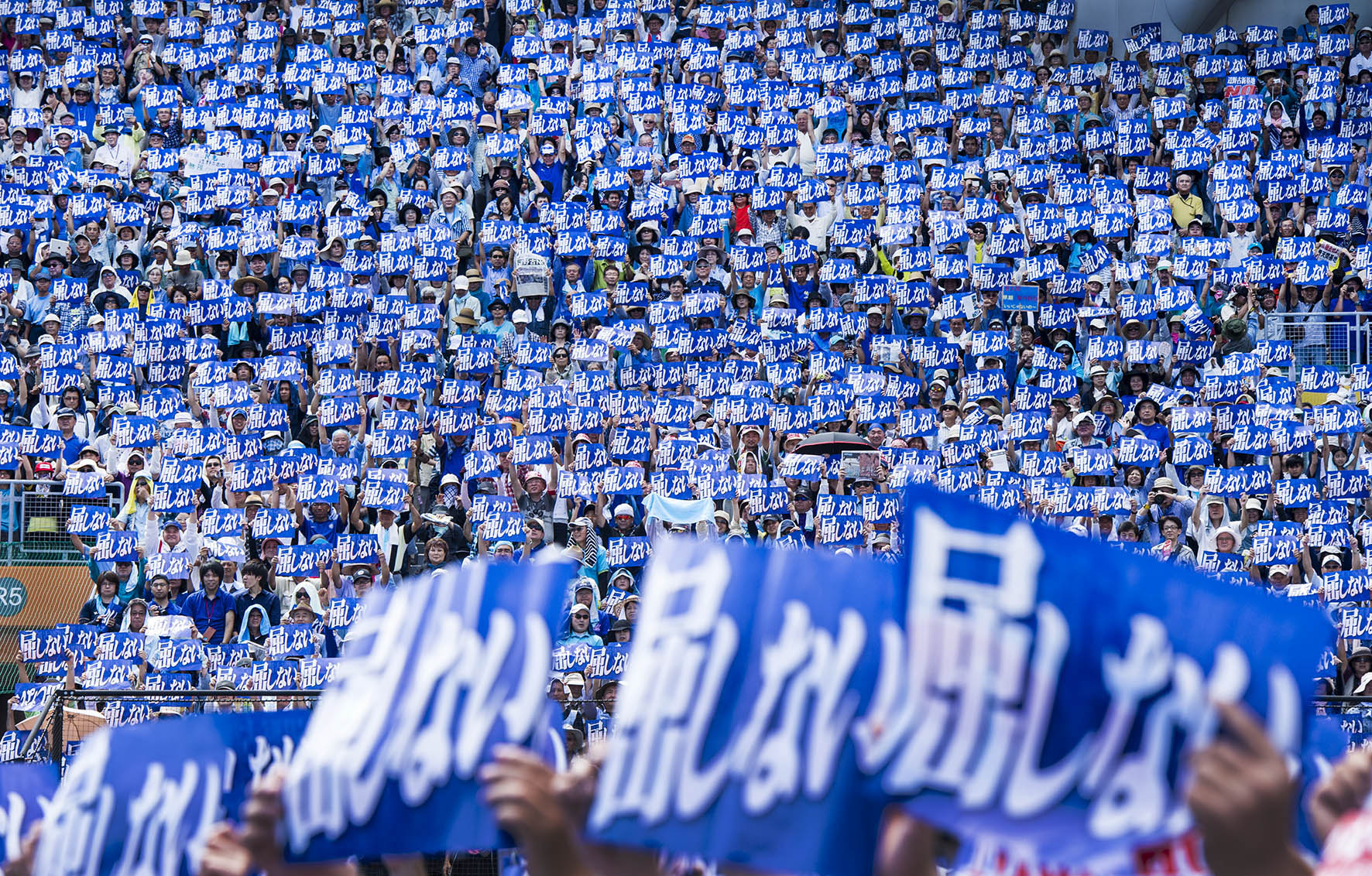

His stay coincided with a turbulent period in Okinawa. Both the Nago mayoral election and the prefecture's gubernatorial election took place in the period, and public opposition rose to the planned relocation of U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to a coastal site at Henoko in the prefecture.

"Of course I also photographed those political events as an extension of our daily lives," Hatsuzawa said. "So I think this photography book is my personal report on Okinawa."

Okinawan Hiroko Arakaki, 32, a musician currently living in Tokyo, was one of the people who attended a talk following Hatsuzawa's book launch. She was impressed by his work for being atypical.

"Hatsuzawa presents multifaceted Okinawa, and not only the blue ocean and U.S. bases," Arakaki said. "I am from Naha, but these photos provide me with different perspectives."

Arakaki also appreciated the title of the book, "Let Us Know About Okinawa," which she said suggests the author took a sincere approach to the subject. She said it might aid dialogue with the Okinawan people.

Hatsuzawa said he hopes people come to see different aspects of Okinawa through his photographs and do not hold on to simplified stereotypes.

"And people should also realize that the reason we hold such stereotypical views is ... the national security policy toward Okinawa," he said.

With your current subscription plan you can comment on stories. However, before writing your first comment, please create a display name in the Profile section of your subscriber account page.