Every year, thousands of young native English-speakers fly to Asia in search of an adventure, financed by working as English teachers. They come from Australia, New Zealand, the U.S., Britain, Canada and elsewhere.

But it can be risky leaping into another country on the promise of an "easy" job. In Japan's competitive English teaching market, foreign language instructors are treading water. "Subcontractor" teachers at corporate giant Gaba fight in the courts to be recognized as employees. Berlitz instructors become embroiled in a four-year industrial dispute, complete with strikes and legal action. Known locally as eikaiwa, "conversation schools" across the country have slashed benefits and reduced wages, forcing teachers to work longer hours, split-shifts and multiple jobs just to make ends meet.

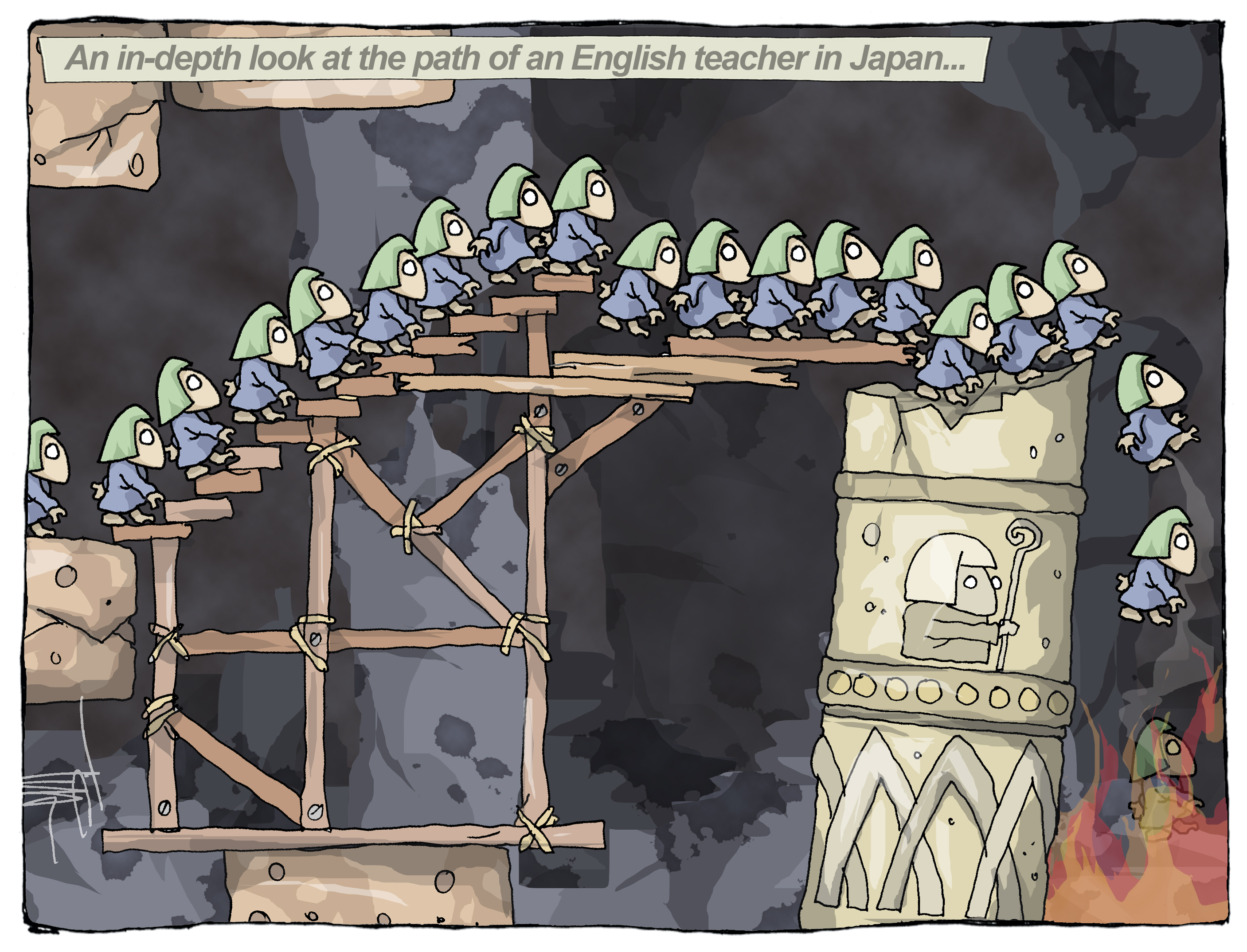

Armed with slick websites and flashy recruiting videos, big chains such as Aeon, Gaba and ECC send recruiters to Australasia, North America and Britain to attract fresh graduates. New hires come expecting to spend their weekends and vacations enjoying temples, shrines and exotic locales. Newcomers may also be lured by the prospect of utilizing that ESL (English as a second language) diploma or CELTA (Certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) they've worked hard for. Yet from the start, they'll effectively be customer-service staff, delivering a standardized product. Recruiting campaigns take full advantage of the prospective teacher's altruistic angels. They look for suckers.