On the platform of a train station in the Paris suburbs, 25-year-old para-athlete Manel Senni braced for another daily odyssey in her wheelchair to go to basketball practice.

"It should take me 20 minutes to get to training, but... I always leave home an hour before," said the young Algerian student who was born with spina bifida, a spinal condition that means she cannot walk.

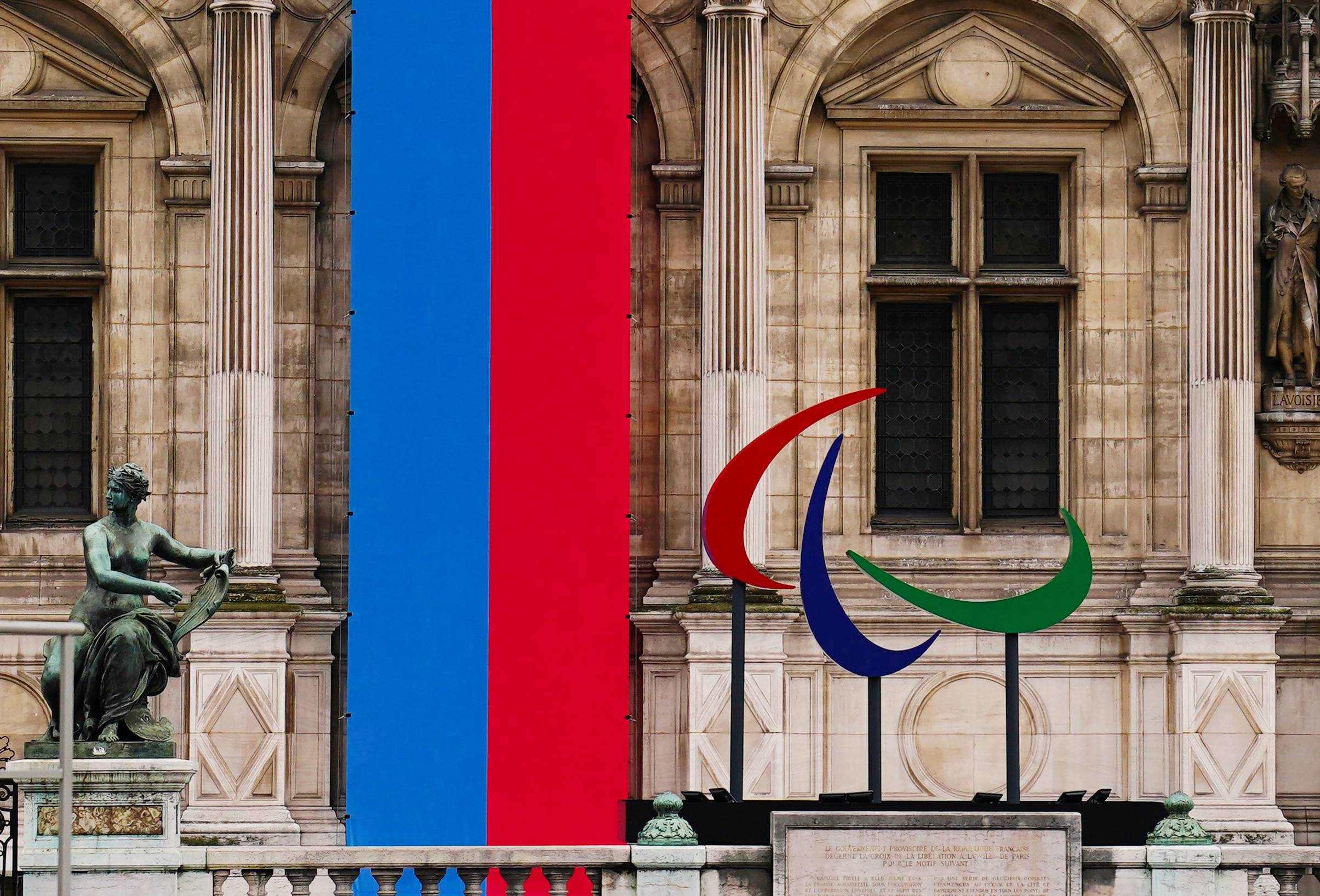

With less than 500 days to go until the Paris Olympic and Paralympic Games, the plight of para-athletes living in the French capital is shedding light on the limited accessibility of its public transportation system.

At Noisy-le-Sec station, a train pulled up, but it was an old model with a 40-cm step into the carriage.

"I'd have to call station workers to set up a ramp for me," she said.

"What I do instead is wait for another train with a floor at the same level as the platform."

This, though, can mean watching up to three trains come and go.

Finally, a train with a lower carriage floor pulled up on the tracks, and Senni lifted her front wheels slightly to ease herself on board.

"This is one of the easiest trips of my week," she said.

On other days she is forced to circumvent the entire city, instead of crossing it, to get to another basketball court.

Two stops later, Senni glided off and easily made her way out of the station. But outside, she discovered her tram had been canceled due to public works.

"This type of thing happens every day, I'm used to it," she said with a smile, before wheeling herself to the sports hall instead.

Not far from practice, a stadium was under construction for the Summer Games next year.

"You can tell that they're really making an effort to properly host the Paris Games," she said.

"But it would be great if they could also focus on transport so that disabled people can come to see them."

Pierre Rabadan, a city official in charge of preparing Paris for the Olympics, said he was well aware of the challenge.

"We know our network isn't 100% accessible," he said.

"We know that, due to its age and complexity, even with the best will in the world, we'd struggle to make all stations accessible even in six or seven years."

While 100% of Paris buses are equipped with ramps and most train stations in the suburbs are accessible to wheelchairs, there is still a lot of work to be done in inner-city subway stations.

Inside the city walls, only one line — No. 14 — has lifts into every station and low-hanging trains speeding up and down the tracks.

In most of the rest of the Paris underground system, mazes of staircases block the way to platforms.

According to the capital's transport authority, during the Games, passengers in wheelchairs will be able to book places in advance on buses to ferry them from main train stations to sports venues.

Patrice Tripoteau, the director of the France Handicap rights group, says this was a good start.

"It won't be able to respond to all situations, but it will cover a large part of them," he said.

"But the measures should be up to the challenges, otherwise a sizeable amount of people will find themselves struggling," he added.