Mark Emmert, the National Collegiate Athletic Association president, supports Japan trying to establish its own college sports governing body.

Emmert, who stopped here after visiting Taipei for the World University Games, was invited to meet a group of leaders that are studying the U.S. model to see what would work when Japan creates an NCAA-type governing body.

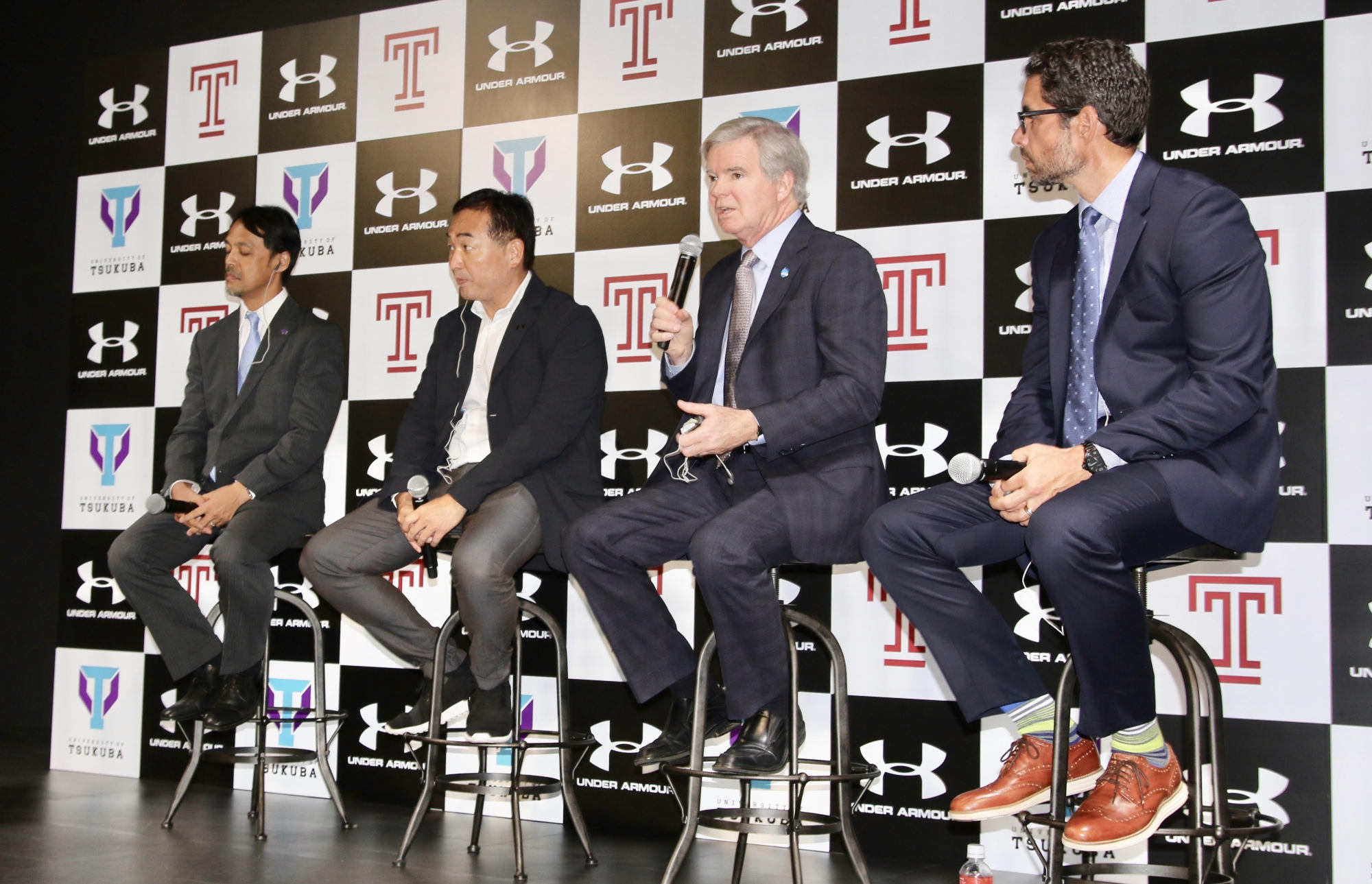

Speaking on Wednesday at a Tokyo event that was dubbed the "State of College Athletics" and held at Dome Corporation, Emmert said that he "jumped at the chance" when he was asked to come to Japan to give some advice because he thought it would be a terrific opportunity.

"You have an extraordinary opportunity," said Emmert, who became the fifth NCAA president in 2010. "You have some wonderful universities in Japan, you have a very strong higher-education infrastructure here with some great schools and you have the enthusiasm of the Olympics in 2020, when your whole nation is going to be focused on sport for the next three years, four years, as you roll into this incredible event of the Olympics."

While Dome Corporation, the University of Tsukuba and Temple University have organized a joint research project on the NCAA since last year, Emmert did not encourage Japan to just emulate what is done in the U.S. because it would not work identically here.

"I'll never, ever want to pretend like we have a perfect model, everything's great, and you (Japan) just do what we do," he said. "Because it's not perfect. A lot of things, we're trying to fix. And you have to create your own organic system."

The 64-year-old said that Japan should "look at many models" around the world because no single example is a perfect fit.

"So you take the best from all the models," Emmert said. "The American version of college sports could only happen in America. And again, create something different that nobody else has."

During his 40-minute speech at Dome, Emmert explained the history of the NCAA, including how and why it was formed in 1904 and how it has expanded from 65 schools to more than 1,100 today. He said that college sports "is now indistinguishable from college life" in the U.S.

Before a primarily Japanese audience, Emmert insisted that the notion that the NCAA operates to generate money is "absolutely wrong."

"Of the 1,100 schools, last year 20 of them had profit (off) their athletic departments. Twenty out of 1,100. All the rest lost money doing sports," said Emmert, who previously served as the president of his alma mater, University of Washington, and as Louisiana State University's chancellor.

Emmert added that college sports endures because they make their students, not just the student-athletes, feel a connection to their schools and enhance the schools' own brand. This may lead to an increase in student applications for enrollment, among other positive influences.

Jeremy Jordan, associate dean of Temple's School of Sport, Tourism and Hospitality Management, said that collegiate sports can add value for a university community and enhance the student experience, "not only for your student-athletes, but for the entire student body."

Daniel Funk, professor and director at Temple's Sport Industry Research Center, pointed out the imbalance in the numbers of university students and university institutions. He showed a chart that cited the fact that the number of university students in Japan is projected to decrease by 35 percent between 2018 and 2031, while the number of universities has increased by 56 percent since 1990.

"This is not a sustainable model," said Funk, who leads the three-entity research project with Jordan. "So universities will have to look for ways to differentiate themselves from other universities in order to attract the student population."

Funk summarized that universities would have to become more innovative and attract more students, and sports could make a difference going forward.

Emmert commented on the academics aspect for student-athletes, saying that the NCAA has a team that checks the academic background of prospective student-athletes.

"We have more than 200,000 high school students per year who want to be college athletes," Emmert said. "And we have to verify their academics before we say, 'Yes, you are good enough to be a student to become an NCAA athlete.' "

UCLA quarterback Josh Rosen made a controversial comment in early August, saying that playing football, the biggest sport in the U.S., at the college level and attending classes is like having two full-time jobs. He meant that the two tasks are not compatible.

Emmert said he understands Rosen's sentiments.

"His coach pointed out that UCLA has the second-highest graduation rate in (the) Pac-12 (Conference) behind Stanford, so obviously student-athletes can be successful as both students and athletes," said Emmert, who earned his Ph.D. at Syracuse University. "(Rosen)'s point is that it is very hard. I agree with it. It is very hard."

He added: "It's very demanding. It takes a lot of energy and discipline, and we, the NCAA, need to continue to make rules and policies that give student-athletes more time to be students. So we just changed rules, (and) in fact, they provide (student-athletes) with a little more relief. I think we have to keep doing that so that they do get a chance to do all the things that they want to do as students, not just as athletes.

"One of the challenges is that many of them believe they are going to be professional athletes. In fact, they are not. They are going to make a living like the rest of us. And we need to get them to have an opportunity to take full advantage of being in the classroom."

In the future, it could be an issue when the Japan's NCAA-style governing body begins. Or it could become an even bigger issue because Japanese college sport teams tend to practice longer and play all year compared to their American counterparts.

At the same time, unlike in the NCAA, Japanese college athletes don't have a minimum grade-point average standard, one that would prohibit them from participating in team activities if they failed to meet it.

"The trick is to find the right balance (between athletics and academics) and sometimes there's too much time spent on sports, there's no question about it," Emmert said.

The Tsukuba-Temple-Dome project is currently in its second study phase, exploring how athletic departments will function in Japan.

The Japan Sports Agency plans to form the nation's college sports governing body during the 2018 fiscal year.