It is convenient to call the escalating geopolitical contest between the United States and China a "new cold war." But that description should not be allowed to obscure the obvious, though not yet sufficiently understood, reality that this new competition will differ radically from the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

The Cold War of the 20th century pitted two rival military alliances against each other. By contrast, the Sino-American rivalry involves two economies that are closely integrated both with each other and with the rest of the world. The most decisive battles in today's cold war will thus be fought on the economic front (trade, technology and investment), rather than in, say, the South China Sea or the Taiwan Strait.

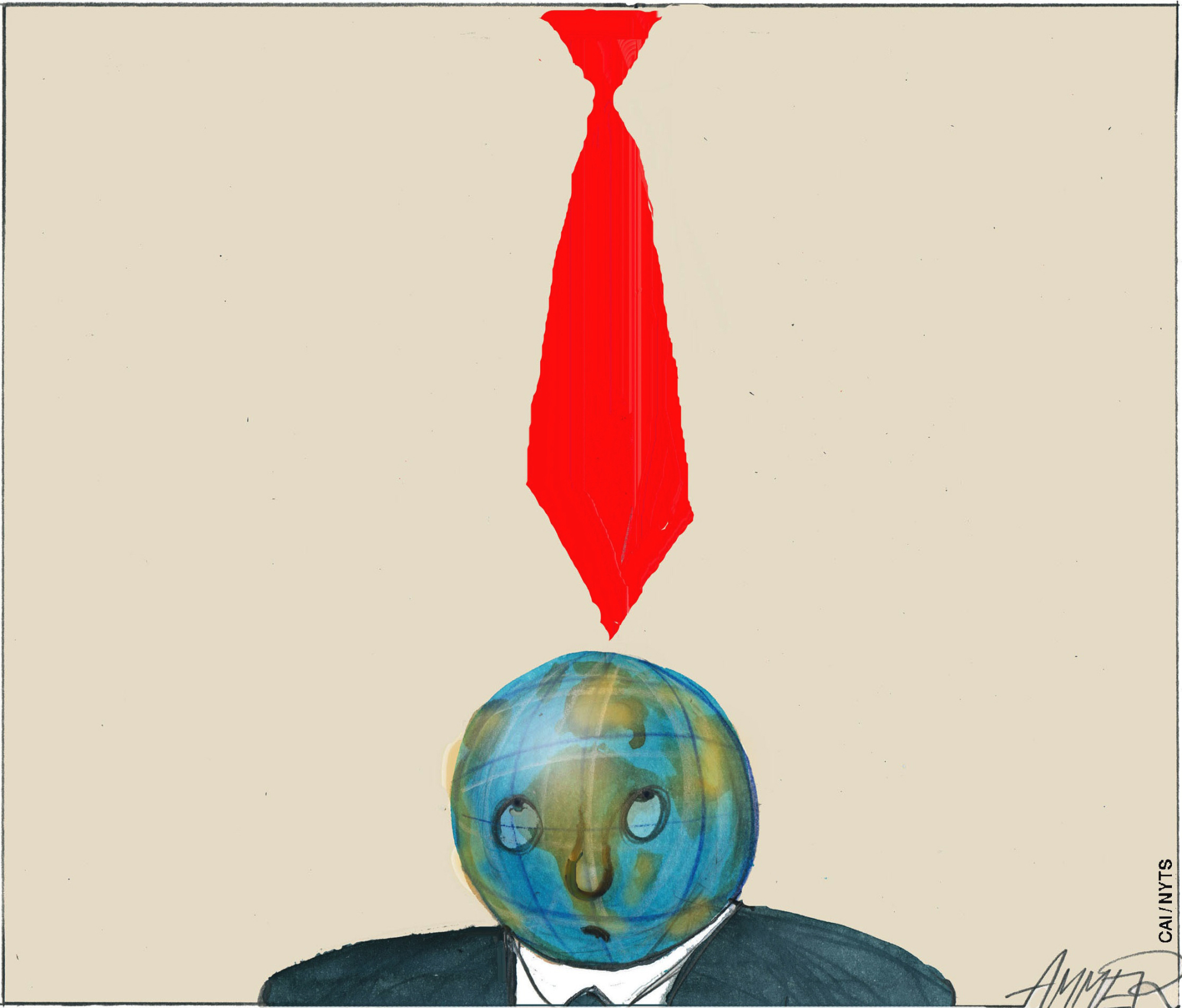

Some American strategic thinkers have recognized this and now argue that, if the U.S. is to win this cold war, it must sever its commercial ties with China — and persuade its allies to do the same. But, as the ongoing bilateral trade war demonstrates, this is easier said than done. Contrary to U.S. President Donald Trump's claim that it would be "easy to win," that war has imposed such high costs, even as the U.S. trade deficit continues to widen, that Trump now seems to be having second thoughts about further escalation.