The political crisis in Venezuela has pitted the United States against a dictator who refuses to leave office. But the crisis has a broader significance: It shows that Latin America has again become an arena in which rival great powers struggle for influence and advantage. As the U.S. faces surging geopolitical rivalry around the world, its position is also coming under pressure in its own backyard.

The region has been the focus of global competition before, of course, from the Spanish-Portuguese rivalry of the 15th and 16th centuries to the Cold War between Washington and Moscow. But after the fall of the Soviet Union, Latin America seemed — for a time, at least — to have become a geopolitics-free zone. The retreat and disintegration of the Soviet Union left the U.S. with no challenger for predominant regional influence. Fidel Castro's Cuba turned inward, consumed by a profound economic crisis. As countries democratized and embraced free markets, the region became essentially unipolar in an ideological sense, as well.

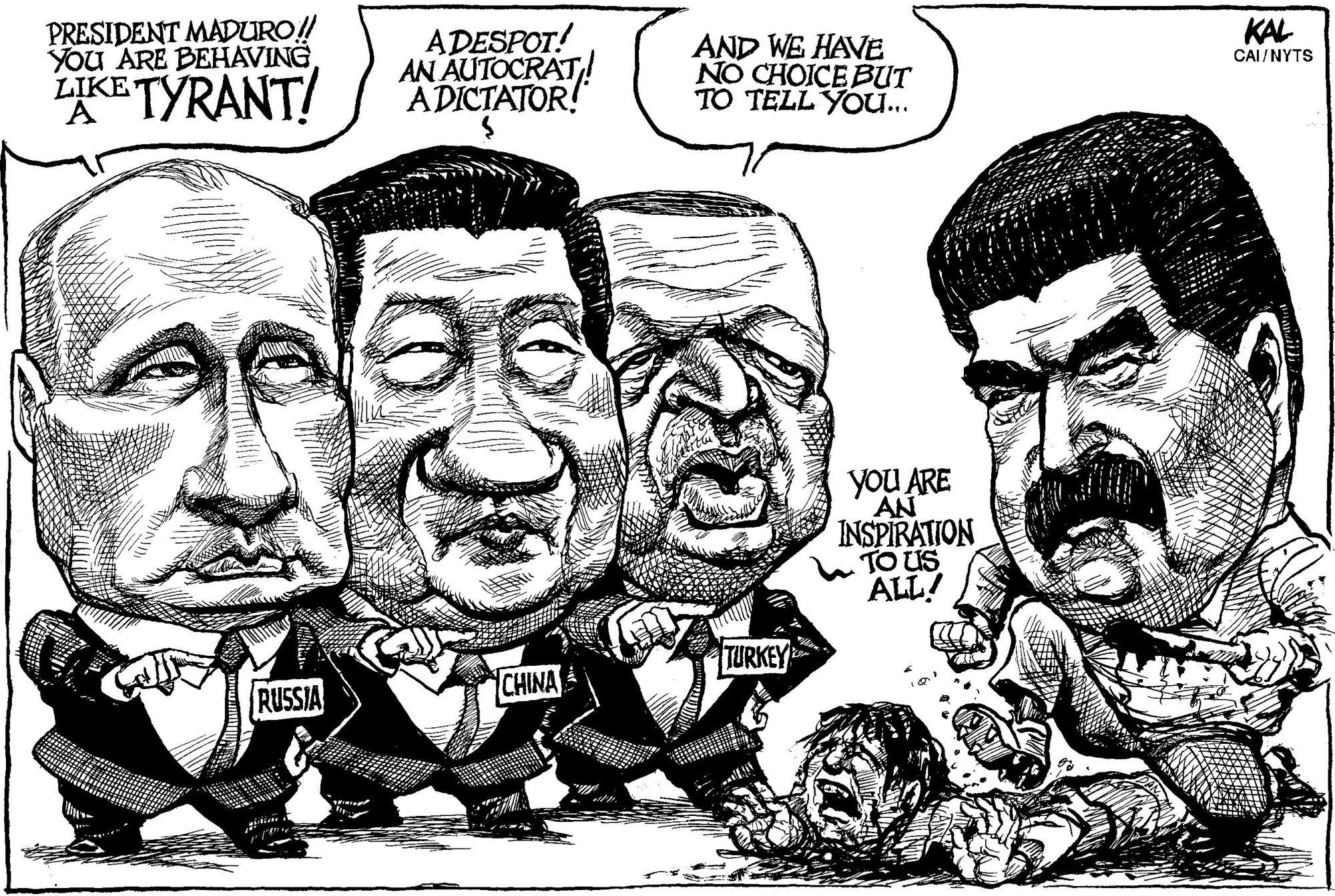

By the early 2000s, however, the climate was shifting. First came a new generation of leaders who viewed neoliberal economics as the source of the region's persistent poverty and inequality. Governments led by the likes of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, Evo Morales in Bolivia and Rafael Correa in Ecuador coupled populist political appeals and economic programs with a penchant for illiberalism and, in some cases, outright authoritarianism. They challenged the U.S. diplomatically and rhetorically, while establishing close ties with Cuba. This created a bloc of regional actors that opposed American power — just as outside actors were beginning to assert, or reassert, their own influence in the region.