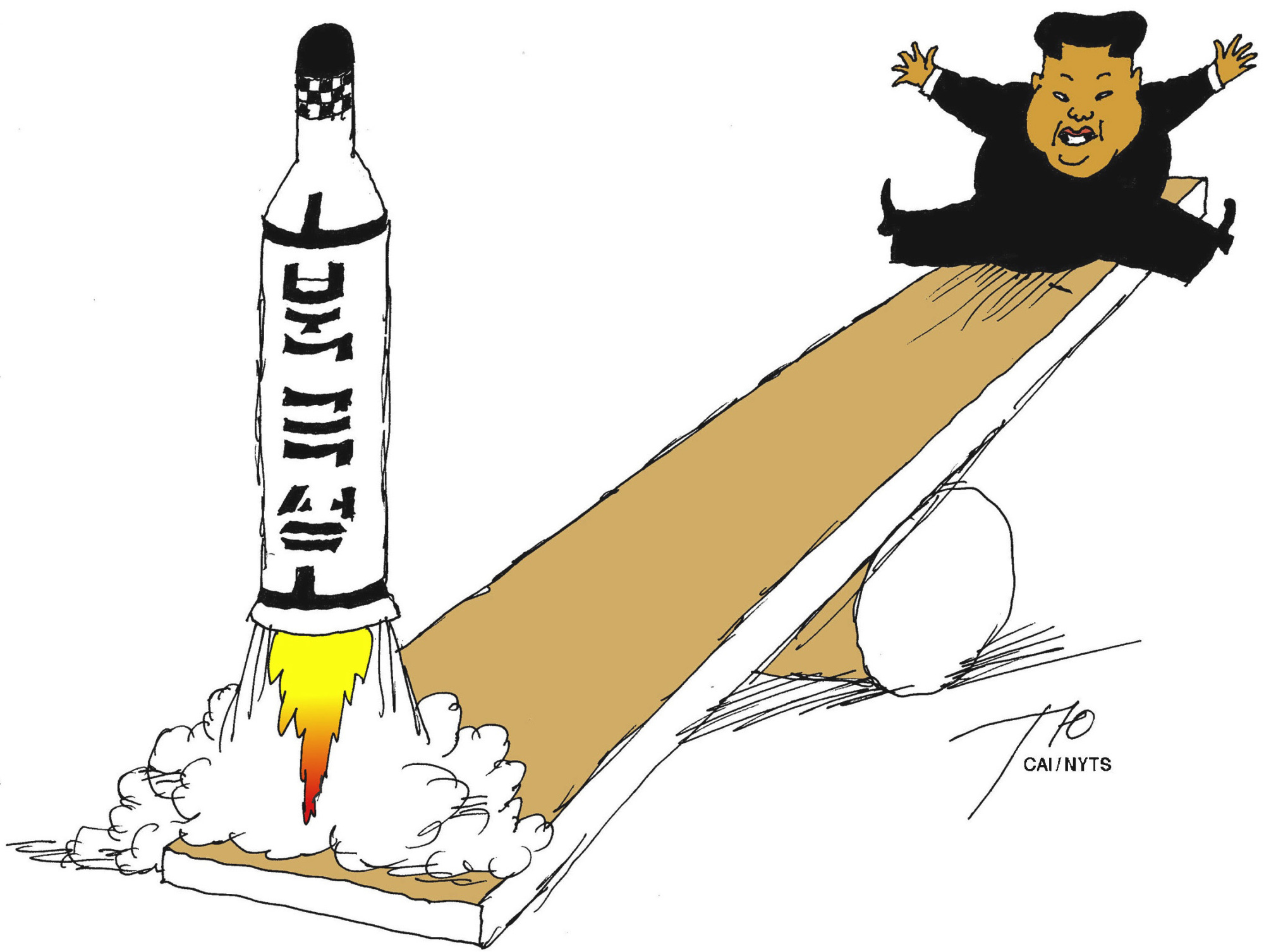

Two weeks have passed since North Korea test-launched the Hwasong-15, Pyongyang's most advanced nuclear-capable intercontinental ballistic missile. Prior to this Nov. 29 test, there was debate among Korean affairs experts over whether a seeming suspension of missile tests by North Korea (no test had been conducted since Sept. 15) might be a gesture on Pyongyang's part to hint that they may be ready to talk. But the latest test ended such debate, at least for now. More importantly, the test confirmed what U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis said months ago — that North Korea is "the most urgent and dangerous threat to peace and security."

In the days immediately following the test, most of the world's attention was on the question of "now what?" — and appropriately so. U.S. President Donald Trump said, several hours after the test, that the United States "will take care of it" and that the missile launch is "a situation that we will handle." The challenge that North Korea presents, however, is that there is no good way for the U.S. to "take care of it, " unless not only the U.S. but China, Japan, South Korea, Russia and the countries that are members of the United Nations Command in South Korea agree that military action is the only way to proceed.

The world's response in the last couple weeks indeed confirmed the absence of good options. Speculation about a U.S. preventive strike against Pyongyang (fueled by comments from prominent political figures, including Sen. Lindsay Graham) continue to swirl. However, as Mattis has said, a diplomatic solution clearly remains a preferred option not only for the U.S. but also for all the countries that have a stake in avoiding another armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula.