Corruption is a cancer to which no society is immune. It raised the death toll of Iran's recent earthquake, owing to substandard housing construction 10 years ago. It has afflicted the United States Navy, which is now investigating more than 60 admirals and hundreds more officers for fraud and bribery. It has brought down countless governments, from Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff's administration last year to Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist government of Taiwan.

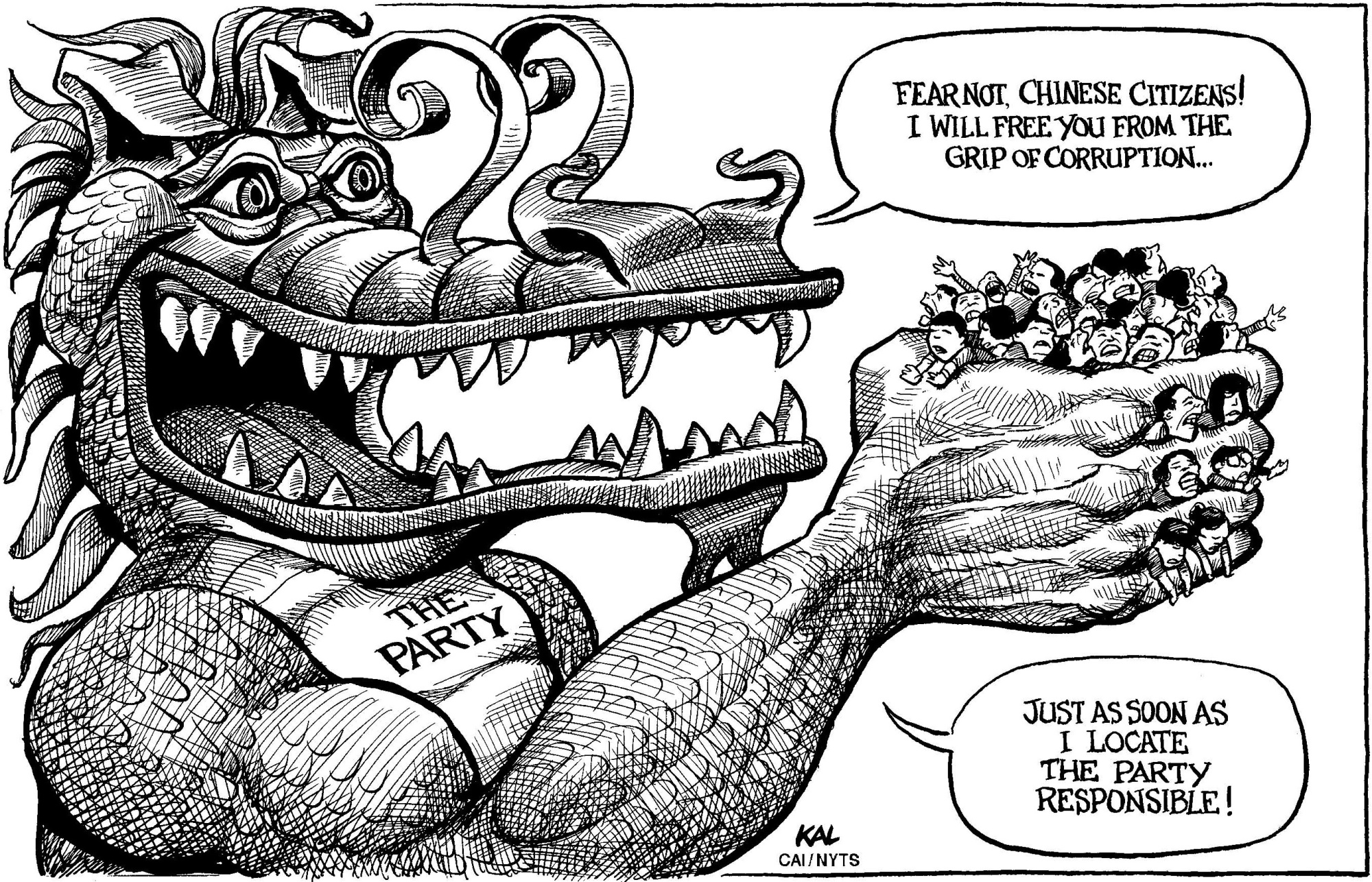

Chinese President Xi Jinping, a keen student of history, is well aware of corruption's destructive potential — and has confronted the phenomenon head-on. But, as China's economy continues to modernize, much work remains to be done.

Prior to the economic reforms of the 1980s, corruption in China was relatively petty, as the market's limited size constrained opportunities for administrative abuse. But, as the market deepened, inadequate legislation and weak institutional safeguards facilitated increasingly brazen corruption and administrative abuses. Meanwhile, as income and education levels rose, citizens became less tolerant of such abuses, increasingly demanding transparent and lawful delivery of basic public goods, from infrastructure to environmental protection, as well as a fair distribution of income and opportunities.