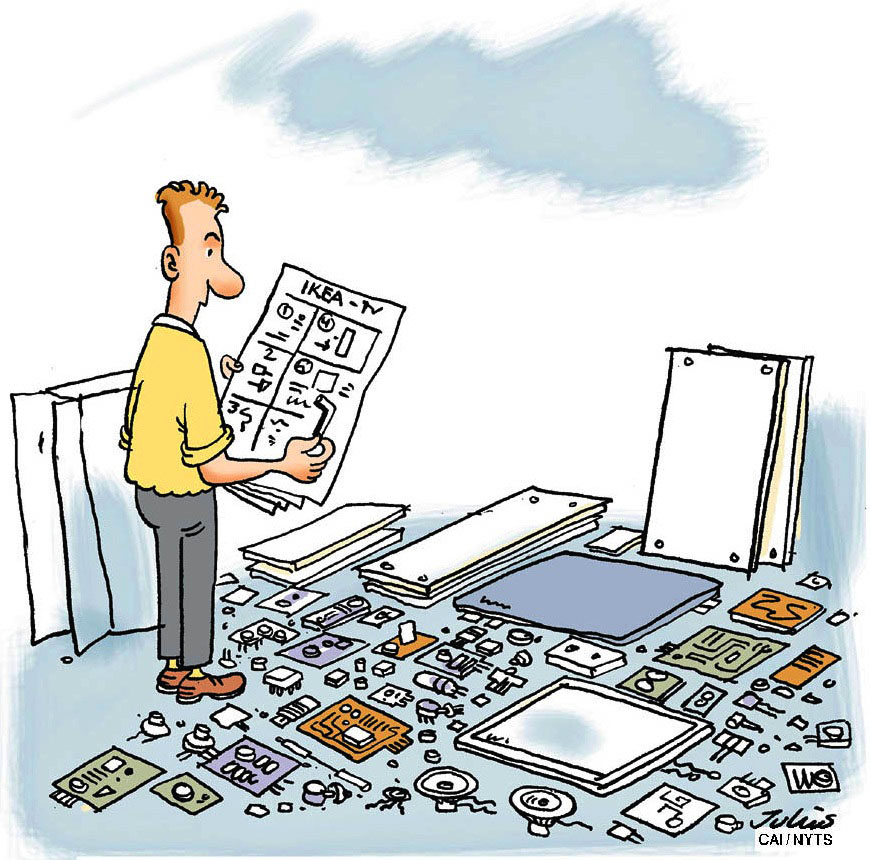

IKEA's acquisition of TaskRabbit, a "gig economy" platform for handyman work, is not just a business move: It's a cultural watershed, an admission by a company that has long been dependent on its customers' manual skills that it can no longer take them for granted.

The idea of selling flat-packed, disassembled furniture probably originated with French designer Jean Prouve in the 1930s. But IKEA founder Ingvar Kamprad copied it in the 1950s from the upscale Stockholm department store NK, which had a line of furniture that could be assembled at home with a set of instructions and a screwdriver. "They had no idea what kind of commercial dynamite they were sitting on," Sara Kristofferson's "Design by IKEA: A Cultural History" quoted Kamprad as saying. "IKEA was able — thanks to the dialog that I later had with innovative designers — to become the first company to develop the idea programmatically in a businesslike manner."

Flat packs and self-assembly certainly helped IKEA streamline its business processes, from shipping and warehousing to keeping a slim workforce. But the approach wouldn't have worked but for something known to researchers as the IKEA Effect. In a 2012 paper, Harvard Business School's Michael Norton and collaborators showed that using one's own hands to assemble a piece of furniture increases its value to a consumer. The psychological mechanism of the effect, which of course isn't limited to IKEA, is known as "effort justification." People value their own hard work; the Norton study showed it doesn't really depend on skill.