For sheer strangeness, Japan's Edo Period (1603-1868) has few rivals. Few foreigners saw it. One who did was the German scholar Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716). We met him in last month's column, on the thronged Tokaido highway, on foot, as were most travelers, bound for the shogun's new capital, Edo (present-day Tokyo).

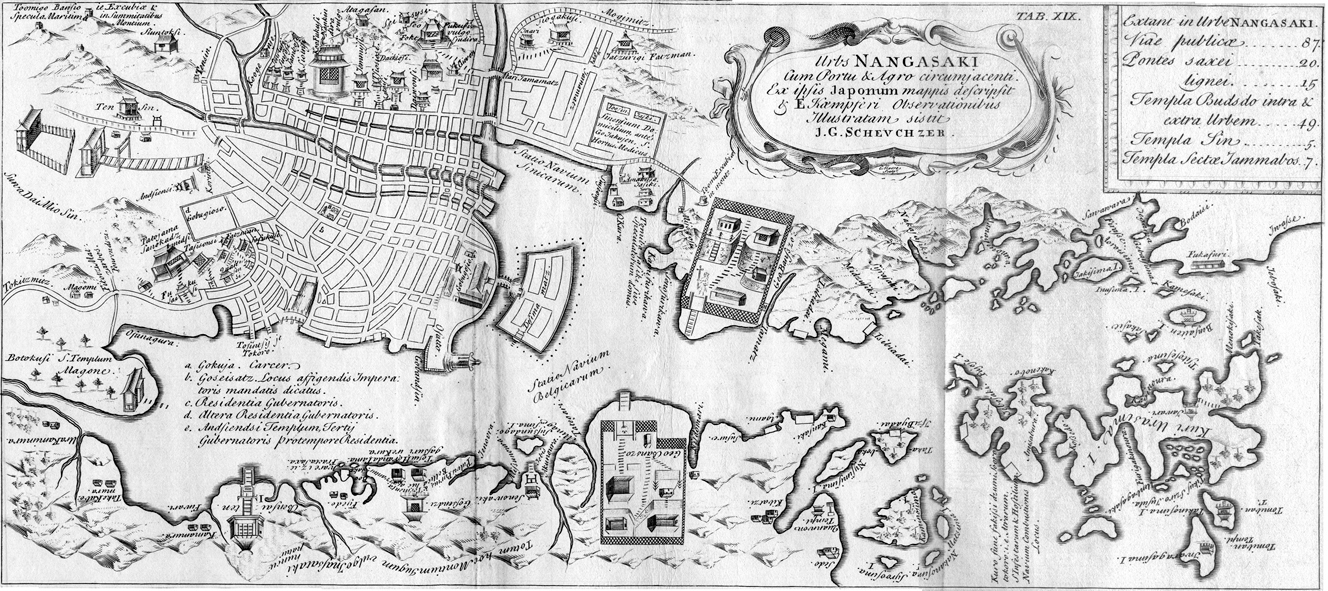

The country was closed to foreigners. Dutch and Chinese traders were rare exceptions. Their base of operations was the tiny island of Dejima off the coast of Nagasaki. It was a tight confinement. Kaempfer shared it with the Dutch East India Company as its resident physician. Company officials were obliged to journey annually to Edo for a formal audience with the shogun. Kaempfer, in 1691, accompanied the mission, recording impressions which years later he included in his "History of Japan" (published posthumously in 1727).

The Japan Kaempfer saw during his two years in the country (1690-92) was in cultural ferment. The famous Genroku era (1688-1704) had begun. Samurai, stymied by peace, lost heart; merchants amassed wealth that mocked the impoverished warriors and their strutting martial airs. The aristocratic arts waned, submerged by the vibrant if crude novels, kabuki plays, music and sexual indulgences of commoners. It was Japan's first pop culture.