On April 15, the day after the first earthquake struck Kyushu, all of the nation's major newspapers carried the same headline: "Shindo 7 in Kumamoto." No further explanation was needed.

When Japan's earthquake-battered populace feels the ground shake, it looks to its TVs and Twitter feeds to check not only the magnitude, but the shindo, or shaking intensity.

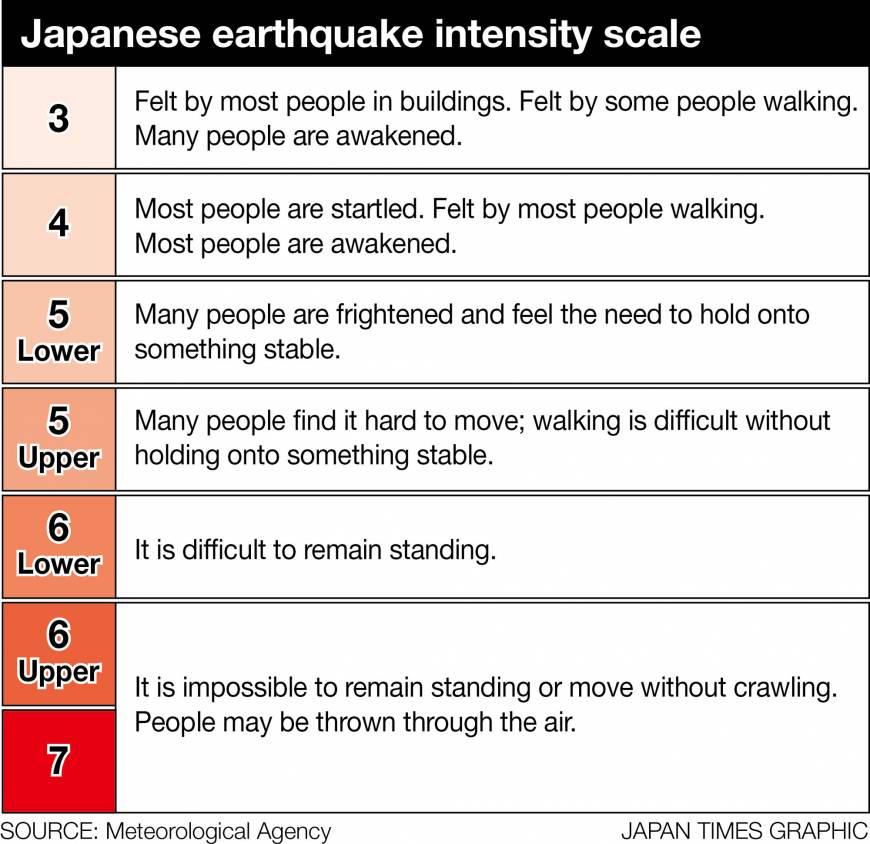

On every TV channel, digital overlays report the region hit and show waves of numbers rippling away from the epicenter: one area might register as shindo level 3, defined as "felt by most people in that zone," another as level 4 ("most people are startled"). The first magnitude estimates typically come later.

A level 7 — the maximum on Japan's earthquake intensity scale — is a panic-inducing event that has been recorded only four times. On each of those occasions people were killed.

While the intensity scale may seem baffling to some, by communicating the intensity of the shaking felt in a specific area, it offers a far more immediate indication of the potential for damage than does the magnitude scale.

Magnitude, which is the value of the energy released at the source of an earthquake, can be a poor indicator of the impact on the surface: A quake of a large magnitude striking deep underground will do far less damage than a smaller one hitting at a shallow depth.

"Earthquake waves are attenuated as they propagate," said Prof. Robert Geller, a seismologist at the University of Tokyo. "They don't attenuate much when the quake is only a few kilometers deep, right underneath a populated area." As magnitude is inferred rather than directly measured, he says, there are discrepancies between the magnitude assigned by different agencies — the 1995 Kobe quake that killed more than 6,000 people was a magnitude 6.9 according to the United States Geological Survey, but a magnitude 7.3 according to the Meteorological Agency in Japan. The magnitude scale is logarithmic, indicating a difference in energy release of almost four times between the two readings.

Unlike magnitude, shindo is a relative, arbitrary measure of the intensity of the shaking in a specific location. The shindo right above the epicenter will typically be the highest, with the level receding as distance grows from the epicenter.

Japan’s intensity scale runs from zero to 7, with levels 5 and 6 confusingly sub-divided into “upper” and “lower.”

The Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011, which spawned the giant tsunami that triggered the Fukushima nuclear disaster, was felt nearly nationwide. The shindo readings ranged from 7 in part of Miyagi Prefecture and upper 5 in parts of Tokyo to a barely perceptible 1 in Kyushu.

There have been only four occasions when a level 7 was recorded, data from the Meteorological Agency going back to 1923 show — the March 2011 quake, the Kobe quake in 1995, the 2004 Chuetsu earthquake that killed 46 and derailed a bullet train, and last week in Kumamoto.

At level 7, the Meteorological Agency says, it is "impossible to remain standing." People may be "thrown through the air," wooden buildings may fall, and even reinforced concrete walls may collapse.

Until 1996, shindo was mostly measured by the agency's staff stationed around the country, who for more than a century reported how strong they felt the shaking and then surveyed the extent of the damage left behind, according to documentation on the agency's website.

Now a network of seismographs spans the country, measuring the initial P-waves when an earthquake strikes. Agency computers collate the data and almost instantaneously issue estimates of its size and likely location.

This network is crucial to informing Japan's early-warning alert system. When an earthquake of a certain size is detected, warnings are issued to iPhones, TV screens and factory lines. Trains automatically halt, and people are given time to prepare before the more damaging S-waves strike.

The warning system has become a source of pride, hailed in government pamphlets as a unique example of national ingenuity.

"It's useful but not perfect," said Geller, "because it gives warnings that let them stop trains for distant quakes but not for quakes right under the track."

In 2013 the agency was forced to apologize after mistakenly warning of an impending magnitude-7.8 quake in the Kansai region that never materialized.