The rusty tracks of an abandoned timber line meander along the edge of a steep cliff overlooking a gurgling, rocky river.

Half-buried in the forest path, these steel rails guide hikers through the mountains of Okuchichibu to where two tributaries join, marking the official starting point of the Arakawa, or “raging river.”

One of the capital’s most important water sources, the Arakawa is also the deadliest river in Japan in the event of flooding — risks being amplified by extreme weather, rising sea levels and other climate-related events associated with global warming.

It is from here, at the western edge of Saitama Prefecture, that the Arakawa begins its 173-kilometer journey. Flowing east down the mountain slopes to the Chichibu basin, the river then turns north through the famed rock terraces of Nagatoro Valley before making its way southeast into the Kanto Plains. After winding through the capital’s densely populated northeastern wards, it finally deposits into Tokyo Bay.

Covering 2,940 square kilometers, the Arakawa River basin is home to approximately 10 million people and spreads across the Tokyo metropolitan area, where one-third of Japan’s population and industries are concentrated. A major source of agricultural irrigation and tap water, the river is, quite literally, the lifeblood of the nation’s economy.

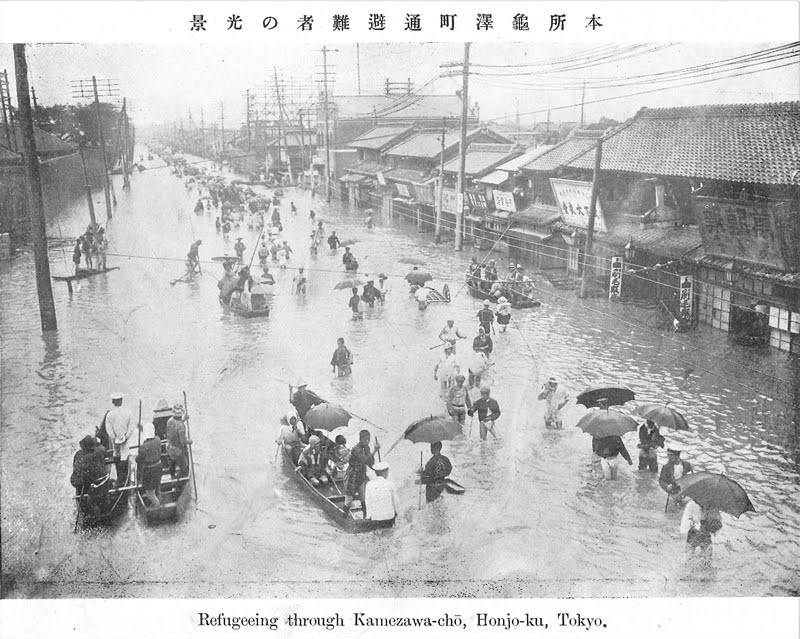

As its name suggests, however, the river has been known for its fiery temperament. Records indicate major floods dating back as far as 858, and more recently, in 1910, when what is known as the Great Kanto Flood saw Arakawa and many other rivers burst when two typhoons coincided with the rainy season, killing hundreds, destroying thousands of homes and inundating the Kanto Plains and much of Tokyo.

While infrastructure projects and high-tech warning systems have since beefed up disaster resilience in cities and municipalities lying near the Arakawa, studies indicate climate change may be putting that to the test, with the frequency of short-duration downpours, also known as guerrilla rainstorms, increasing over the past few decades.

“In terms of the potential scale of damage it could inflict, the Arakawa tops all the rivers in Japan,” says Norio Tanaka, a professor at Saitama University’s Graduate School of Science and Engineering. “If it floods in Tokyo, the impact will shake the nation’s entire economy.”

Flood hot spots

Historically, there have been five main areas along the Arakawa that have been prone to flood hazards, says Tanaka, an expert on river engineering.

The alluvial fan — a triangular spread of sediment — near the city of Kumagaya in Saitama Prefecture has seen frequent flooding, as well as the town of Yoshimi, south of Kumagaya, which lies near the river. The Iruma River, part of the Arakawa river system, has seen its banks overwhelmed during bouts of heavy rain, while the town of Kawajima, sandwiched between the Arakawa and Tone rivers, has seen its levees breached around 30 times over the past 300 years, according to Tanaka.

“The fifth and final point is after the Arakawa is joined by the Iruma River. If the Arakawa No. 1 Retention Basin (located in Toda, Saitama Prefecture) is unable to control floodwaters and the right bank of the Arakawa bursts, Tokyo and its city center will be in danger as floodwaters could inundate subway systems and underground shopping centers,” he says.

The land ministry has simulated one similar scenario in detail: Record-breaking heavy rains triggered by a typhoon see rainfall exceeding 680 millimeters over three days in the upper reaches of the Arakawa in the mountains of Chichibu. At 3 a.m., water levels rise dangerously at the Iwabuchi sluice gate at the junction of the Sumida and Arakawa rivers, leading local governments to issue evacuation orders.

At 4 a.m., the river breaks loose at the capital’s northern Kita Ward, at a location approximately 21 kilometers from the mouth of the river. Muddy streams spill into the city, expanding rapidly. By 10 a.m., the water reaches Machiya Station on the Chiyoda subway line and, by 11 a.m., Kita, Itabashi, Arakawa, Adachi and Taito are among the central Tokyo wards being flooded.

By 5 p.m., many of the subway lines running through the city center have been submerged, and office districts in Chiyoda and Chuo wards have lost all power.

In total, 160 square kilometers of land is inundated, impacting 1.8 million people. An estimated 3,100 people die in the disaster, and up to 700,000 remain isolated a day after the flooding, according to this particular sequence of hypothetical events. Most of Tokyo’s lifelines are paralyzed, and it will take between two weeks and a month for the water to drain, devastating the domestic economy.

“People tend to forget that there’s an interval between the time of maximum rainfall intensity to the time of the peak rate of stream flow,” says Katsuhiro Tsuji, deputy director of the Arakawa-Karyu River Office.

When Typhoon Hagibis made landfall on Japan’s mainland and wreaked havoc in October 2019, the water level of the Arakawa peaked well after rainfall ceased and evacuees returned home.

The typhoon, which killed more than 100 and collapsed levees on more than 70 rivers, saw the Iwabuchi sluice gate in Kita Ward close for the first time in 12 years to prevent water from the Arakawa entering the Sumida River, whose embankments are lower than the Arakawa and thus more vulnerable to flooding.

And on the morning of Oct. 13, after the typhoon had passed, the Arakawa’s water level reached 7.17 meters — the third highest level recorded since World War II and alarmingly close to the 7.7 meters considered a dangerous threshold.

Over the years, various infrastructure projects have been budgeted to reduce flood damage. In the Arakawa’s upstream Chichibu region, for example, there are three dams that retain water during heavy rainfall — the Urayama, Futase and Takizawa dams.

Meanwhile, so-called super levees — gigantic mounds that are 200 to 300 meters wide and can integrate commercial, residential and public spaces — have been built in low-lying or densely populated urban areas where flooding could potentially lead to serious consequences.

“Many residential neighborhoods near the Arakawa are situated in areas below sea level and could flood, for example, if an earthquake destroys levees. In order to prevent that from happening, construction work is ongoing to reinforce the foundation of dikes,” Tsuji says.

In 2019, the capital’s Edogawa Ward updated its hazard map for the first time in 11 years, urging residents to flee from the ward to other areas in the event of wide-scale flooding. Sandwiched between the Arakawa and Edogawa rivers and facing Tokyo Bay, 70% of its land is below sea level, making it one of the most vulnerable among the city’s wards to disasters caused by torrential rain, typhoons and high tides.

It’s not only Edogawa Ward. Most areas in the low-lying “five wards of Koto” in eastern Tokyo — also including Adachi, Katsushika, Koto and Sumida — will be submerged in a worst-case scenario, affecting 2.5 million people, or more than 90% of the entire population of the five wards combined.

While a combination of dams, retention reservoirs and the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel — the world’s largest underground drainage channel in Kasukabe, Saitama Prefecture — helped avert a similar scenario during Hagibis’ landfall, things could have taken a turn to the worst if it had rained more or if the storm traveled a little more slowly.

Taming the beast

For centuries, managing and controlling the Arakawa has been a priority for the nation’s leaders.

Before the Edo Period (1603-1868), the path of the Arakawa and other rivers flowing into Tokyo Bay were volatile and susceptible to changing courses during floods — akin to eels thrashing around in the mud.

When feudal warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu founded the Tokugawa shogunate, he embarked on an ambitious infrastructure drive to develop the Kanto Plain through flood control and irrigation.

Ieyasu ordered the eastward relocation of the Tone River to mitigate flood risks, create farmland and improve ship transportation logistics — a project that began in 1594 and took 60 years to complete. Then, in 1629, construction commenced to separate the Arakawa from the Tone River near Koshigaya in present-day Saitama Prefecture so it flowed into Tokyo Bay via the Sumida River.

But that didn’t tame the Arakawa. As the nation’s population soared and urbanization progressed during the Meiji Era (1868–1912), flood damage re-emerged as a serious concern, according to Nobuyuki Tsuchiya, a civil engineering expert and technical counselor at the Japan Riverfront Research Center.

Triggered by the Great Kanto Flood of 1910, the Meiji government launched a massive project involving the construction of a floodgate in the Iwabuchi district of Kita Ward and digging a 500-meter-wide drainage canal extending 22 kilometers from Iwabuchi to Tokyo Bay. This would allow the Iwabuchi sluice gate to close during floods to control the rise of the main branch of the Arakawa and enable most of the water to run straight into the sea.

The work was finished in 1930, and the drainage canal was renamed the Arakawa in 1965. Meanwhile, the old Arakawa branching from the Iwabuchi sluice gate came to be called the Sumida River.

That didn’t prevent major storms from flooding the Arakawa, however. In September 1947, Typhoon Kathleen struck the Kanto region and caused the Arakawa and Tone rivers to overflow, triggering disastrous flooding that killed 1,077 people and left 853 missing.

“In recent years, the government and municipalities have been investing in super levees and other projects to enhance flood resilience. But these initiatives will take decades for completion,” says Tsuchiya, author of “Shuto Suibotsu” (“The Capital Submerged”). “There’ve also been plans to move part of the capital’s functions elsewhere to mitigate risks, but Tokyo remains the economic and political center of Japan.”

That means residents in flood-prone areas need to be prepared for the worst. The 2020 version of the white paper on disaster management says the frequency of heavy rains, major flooding and landslides have been increasing due to global warming, and that Japan needs to brace for meteorological disasters of an unprecedented scale.

Tsuchiya also warns of earthquakes, especially the anticipated shuto chokka jishin (earthquake directly beneath the capital) that seismologists warn could happen any time.

Just over 18% of earthquakes in the world take place in Japan, which sits on or near the boundaries of four tectonic plates. In 2013, the government issued a report predicting that there is a 70% chance of a magnitude-7 earthquake striking the capital region in the next 30 years.

“What would happen then? Besides the various scenarios anticipated, we will also likely see levees destroyed and rivers spilling out of control,” Tsuchiya says.

The expansive subway network stretching from Saitama to Kanagawa prefectures and the proliferation of asphalt-covered roads can also accelerate the spread of floodwater and give it a wider reach. Meanwhile, small, wooden homes and makeshift facilities crowd numerous neighborhoods in Tokyo, meaning many houses could be severely damaged in the event of major flooding.

“Even with ample warning, there are going to be people isolated if the Arakawa floods,” says Yasuo Matsushima, who heads the Disaster Risk Assessment Research Institute consultancy.

“They could be the elderly, families with small children or those stranded since heavy traffic congestion is expected as people try to escape water-trapped wards via bridges,” he says.

Electricity will be lost, and just 3 meters of water is enough to reach the second floor of structures, he says. And there won’t be sufficient public facilities for those in submerged areas to seek refuge.

“That’s why it’s important for both individuals and communities to decide on where to flee in case the Arakawa floods,” he says.

In the final scenes of “Weathering With You,” Makoto Shinkai’s award-winning 2019 feature animation, much of Tokyo is drowned in water after years of nonstop rain. As improbable as that may seem, there’s only so much precipitation the “raging river” can take before it climbs over its banks once again, engulfing anything that stands in its way.

Resting by a road running near the Iwabuchi sluice gate is a stone jizō statue donning a red hood and clutching a staff. A wooden sign next to the Buddhist deity explains its significance:

“This jizō was built by local volunteers to commemorate the many water accidents of the past.”