It is often said that the passenger pigeon, once among the most abundant birds in North America, traveled in flocks so enormous that they darkened the skies for hours as they passed. The idea that the bird, which numbered in the billions, might disappear seemed as absurd as losing the cockroach. And yet hunting and habitat destruction pushed the animal to extinction. Martha, the last known passenger pigeon, died in 1914 at the Cincinnati Zoo.

Plans are afoot to bring back the bird by using a weird-science process called de-extinction. The work is being spearheaded by Ben J. Novak, a young biologist who is backed by some big names, including the Harvard geneticist George Church. The idea was recently promoted at a TEDx meeting in Washington and is being funded by Revive and Restore, a group dedicated to the de-extinction of recently lost species. (Other candidates include the woolly mammoth and the dodo.)

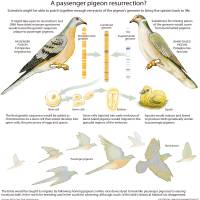

Working with Church's lab and Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California at Santa Cruz, Novak plans to use passenger pigeon DNA taken from museum specimens and fill in any blanks with fragments from the band-tailed pigeon. This reconstituted genome would be inserted into a band-tailed pigeon stem cell, which would transform into a germ cell, the precursor of egg and sperm. The scientists would inject these germ cells into developing band-tailed pigeons. As those birds mate, their eventual offspring would express the passenger pigeon genes, coming as close to being passenger pigeons as the available genetic material allows.

The process is not the same as cloning. Novak's approach would use a mishmash of genes recovered from different passenger pigeons, resulting in birds as unique as any from the original flocks. Most pigeons mature and reproduce quickly enough that the de-extinction process could be completed in less than a year. Producing a flock large enough to release into the wild would take at least another decade.

Novak says he is confident the procedure will work. "Essentially, the genomes of the band-tailed pigeon and the passenger pigeon, I think, will prove to be similar enough to easily convert one to the other," he said.

Experts say there is little question that re-creating the pigeon is technically possible. Indeed, the genome of the woolly mammoth has largely been sequenced using elephant DNA as a scaffolding. Complete, working genomes of dogs, sheep, horses, cows and other species have been artificially inserted into egg cells to produce living organisms.

But the project still faces many challenges, among them the contamination of much of the DNA specimen. The hundreds of passenger pigeons in museum collections have been exposed to heat and oxygen. Specialized equipment would be used to identify the surviving fragments of DNA and reassemble them into working genes. It's a painstaking process that could take years.

But the larger problem, say some scientists, is that even if the passenger pigeon is re-created, it's unlikely to be viable as a species in today's ecosystem. Novak's plan is to breed the first new generations of the bird in captivity. But eventually he hopes to release birds into the wild.

Such a proposition, some experts say, poses a number of fundamental problems: There is some question as to whether today's forests can support a restored passenger pigeon population, and its nesting behaviors make the bird particularly susceptible to dying out again.

"Much of their breeding and wintering habitat is gone," says Scott C. Yaich of the conservation group Ducks Unlimited, and their primary breeding-season food — beech mast, the nuts of beech trees — is limited.

The birds "simply couldn't be restored to a landscape that is so radically altered from the one to which they were uniquely adapted," says Yaich, director of conservation for Ducks Unlimited.

But Mark Twery, a research forester at the U.S. Forest Service, says that though beech bark disease has reduced beechnut production, "the overall quantity of forested habitat is likely to be ample to support a large enough number of pigeons for a viable population."

Other experts say that given the nesting behavior of the passenger pigeon, releasing a handful of birds into the wild would be a losing proposition.

The mainstream view of passenger pigeon ecology is that they used a reproductive strategy called predator satiation. The recent cicada invasion in the U.S. Northeast is one example of this strategy. Each cicada is individually easy to catch in its slow, bumbling flight. But there are so many millions of cicadas in a spot at one time that they are able to finish mating and laying eggs before predators have had time to eat all of them. If only a few thousand cicadas emerged at once, then most of them would probably be eaten before they were able to reproduce. In this way, the cicada's survival depends on showing up in hordes.

Passenger pigeons succeeded through a similar sort of mob rule. Individually, their behavior was borderline reckless. They built flimsy nests, often dangerously low to the ground. The nests were built so hastily that when bad weather would slow down construction, a female would sometimes be forced to lay her eggs on the ground. When the young were ready to leave the nest — after only 14 days of development — they would spend their first few days on the ground, vulnerable to any hungry predator.

Passenger pigeons could get away with such behavior because of their incredible numbers. When a flock arrived at a nesting area, predators could gorge themselves for weeks. Each pair of nesting pigeons would produce two eggs, at least one of which usually ended up on the ground. But even with the constant work of foxes, bears, possums, raccoons, hawks, eagles, snakes and other meat-eaters, enough of the young pigeons survived to fly away.

This system works great with a flock of 5 million birds. But according to Kirk Mantay, a biologist specializing in habitat restoration, if only a few thousand pigeons show up, the whole system falls apart.

"If you put 5,000 out there, even with good habitat, they could all still be gone in a few decades unless you could exclude the predators somehow and make sure that they nested right where you wanted them to go. You just couldn't make enough birds for it to work."

A handful of nests and fledglings might escape the notice of predators, but as soon as the colony grew to a few dozen nests, the noise and scent would bring those predators in to feast on easy meals. You would need to skip ahead to millions of birds for the predator satiation strategy to properly work.

Still, "I believe the passenger pigeon will survive because we have people committed to its survival," Novak says, citing the reintroducton of the condor into the wild in California. Those birds, on the verge of extinction, were bred in captivity, then gradually released beginning in the 1990s; there are now about 200 living in the wild.

Would a commitment to its survival be enough to sustain the passenger pigeon? A few specimens living in an aviary would be a historic accomplishment. But an effort to put the birds back into the wild would be challenging at best.

"Habitat restoration is hard to get right for species like turkey and quail that we know about," says Mantay. "How long is that going to take with something we can't study in the wild first?"

Landers is the author of "The Beginner's Guide to Hunting Deer for Food" and "Eating Aliens."