Dating from 1892, Tsukishima is Tokyo's oldest island of reclaimed land — and also its monjayaki Mecca. Once a cheap after-school treat cooked on griddles in working-class neighborhoods of postwar Tokyo, monjayaki has morphed into a dinner entre — and Tsukishima is the place to try it.

Originally, moji-yaki was a simple flour-and-water mixture poured out to write the name of the child ordering it. Now, though, it's become a savory pancake loaded with ingredients similar to okonomiyaki, minus the eggs. Monja, as it's known for short, tends to divide diners into "love it" or "hate it" camps. I exit the Oedo Line's Kachidoki Station and stroll northeast to Nakanishi Dori avenue to find out which camp I fall into.

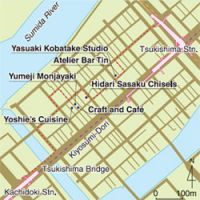

The "love it" contingent made Yoshimiya, 1954's first monja restaurant on Nakanishi, so popular, the story goes, that all the other shops decided to catch the wave of monja mania. Now, under Nakanishi's promenade of little peaked roofs and feeder alleys, there are more than 60 such mini-restaurants.

I choose Monja Yumeji, a restaurant with a sculpture outside named "Yorokobi Shojo" ("Happy Little Girl"), by Seibou Kitamura — creator of the Nagasaki Peace Statue. I'm hoping it will make me happy, too. As proprietor Yumiko Komatsu explains her interest in the arts — her shop is named for another famous Japanese artist, Takehisa Yumeji (1884-1934), and she runs a private art museum in Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture — the monja arrives.

It starts out looking harmless enough. A bowl of chopped cabbage, laden with some pork, squid, shrimp and bacon.

The sharp young waiter — Yumiko's son's friend — eases this lot onto the grill, then chops at it cheerfully to the beat of the restaurant's rap music, subduing the ingredients with two hagashi, or metal spatulas. I glance nervously at the watery slurry of flour and seasoning still lurking in the bowl. It's that which I've heard renders the meal a little too mucoid for some; I'm hoping the waiter has decided to leave it out. Once the veggies and meat go limp, though, he arranges them into a circular atoll, then dumps in the lagoon of goo. I force on a happy face.

Rarely pusillanimous with food, I find the stuff looks somewhat regurgitated. It's also hot as the dickens. I try it anyway, and find it's not bad, actually. With a shake of nori (laver) flakes, a drizzle of sauce, and grilled to a crisp, it's tasty and filling.

With my monja mojo on, I depart the main drag, ducking down an alley canopied in greenery and humming with cicadas. There are more tiny eateries here, among bikes, buckets, fish bowls and shadows. I stop in front of a framed painting on the outside wall of one home.

"The artist is our friend, and he told us to hang it out here, because this way more people can see it," explains Yoshie Morimura. Owner of Yoshie's Cuisine, a cooking school specializing in worldwide cooking techniques, Yoshie, 42, is as friendly and uninhibited as an old friend. "Currently, I'm teaching Thai dishes," she announces, "and I'd love to have foreign students."

She guides me next door, where her cousin, 56-year-old Hiroshi Otake, runs Cafe Craft, a coffee shop cum woodworking and pottery studio. I get the feeling that Hiroshi is dubious on the concession aspect of his business, but his woodwork in carved maples and Bizen-style pottery is quite beautiful. "You know it's hard for artists to live on art alone," Yoshie reminds me. Hiroshi is quick to add that he also teaches pottery classes and his fees (¥2,000 per session) are more than reasonable.

Yoshie walks the backstreet with me for a bit and we turn a corner just in time to gape at Hisao Mitami, 56, leaving his funeral home business for a walk with his 50 kg, 15-year-old pyramided Sulcata tortoise — Bon-chan. "He knows the way," Mitami says, taking one step to Bon-chan's four, and offering chunks of carrots as trail snacks. "He grew much larger than I expected, and he's going to get larger."

I follow Mitami, marveling at the irony of a funeral director with a pet touted in Japanese mythology as living for 10,000 years. Greeted by local cats, allowing passersby to pet him, and even giving a short ride to a toddler, Bon-chan is clearly a living local treasure.

He has his match in patience and accolades in Nobuyuki Ikegami, the 54-year-old third-generation hamono (chisel and knife) master diagonally across the street from Bon-chan. Out of respect for his neighbors, Ikegami only fires up his forge in the early morning hours. The rest of the day, he quietly shapes and sharpens his superlative blades, laminated in a unique "W" shape for strength and resilience. Working almost exclusively on atsurae (custom orders through interviews and detailed assessment of the customer's needs), Nobuyuki started to learn his skill at the age of 3, at his father's side.

"He was wonderful to learn from," Nobuyuki says, his huge hands resting in his lap, his eyes briefly carving the ceiling of his humble abode. "I can now make anything he made, and a few things he didn't," he says, showing me a delicate chisel prized by craftsmen who carve the bridges of violins. Nobuyuki says he studied for 24 years before making a piece he felt he could call his own; now it's all he can do to keep up with orders from around the world.

When Nobuyuki takes up one of his chisels and proceeds to carve a piece of solid steel, I cringe. He laughs. His chisel is utterly unscathed. Then, as I finger an astounding mokume gane chisel, made of blended metals that resemble wood grain, Nobuyuki nods at my appreciation.

"If I could speak English," he says, "I'd warn people about poorly made, but expensive Japanese tools available on the Internet, because it hurts the serious craftsman's reputation."

I am still pondering the fact that Ikegami blends high-quality metals from Kamakura Period (1192-1333) temple hinges and nails to make his tools when I pass a house surrounded by metal piano guts, odd slabs of steel and wires. I have metal on my mind, so I have to check it out.

Peeking into the dark interior of a mini-warehouse, I find sculptor Yasuaki Kobatake about to fire up an acetylene torch. When I ask if I can come in, he nods, but adds cheerfully, "Sometimes these things blow up." I watch from the safest corner of the studio I can reach as he straps on leather arm-sleeves. "Like a samurai," he jokes, striking the flame, and filling the room with a hissing glow.

"Don't look directly at the flame," Yasuaki warns, and of course I stare as he slices a pie piece out of a huge steel disk, sending showers of sparks everywhere.

Yasuaki tells me he is working on a large sculpture for an upcoming show at the National Art Center, Tokyo (Oct. 30 till Dec. 6), and shows me several of his elegant, vaguely planetary lacquer-coated steel structures.

A native of Tsukishima and son of a steelworker, Yasuaki loves operating massive lathes and welding machinery, and says it reminds him of his father.

When I ask him about the neighborhood, I learn that the studio we are in, and much of the entire block, is scheduled to be torn down and replaced with a large residential apartment building. He quickly explains, "Many of the buildings here now are 70 to 80 years old, and they're really not safe."

Perhaps he is right, but I have an instant desire to run out and enjoy the neighborhood while I can.

"Culture lives in these shadows," says Atsushi Shibata, owner of Atelier Bar Tin, in the same building as Yasuaki's studio, and decorated with his metal works. Over chilled wine, his clientele — engineer Peter Schonstein, 56, his wife, Kazuyo Kitada, 41, and Carl Wooden, 53 — launch a bilingual discussion on the pros and cons of development.

"We were spared the bombings during World War II," Shibata says, "because Seiroka Hospital was nearby. But all this will be gone in about three years." A brief silence falls over the bar as the heat of the discussion, and the day, dissipates, and early evening settles on Tsukishima.

Kit Pancoast Nagamura and Kyoko Tsuchiya are proud to announce that their new book, "The Ultimate Japanese Phrasebook" (Kodansha International; ¥2,600), an invaluable resource for students of Japanese, will be in bookstores from October.