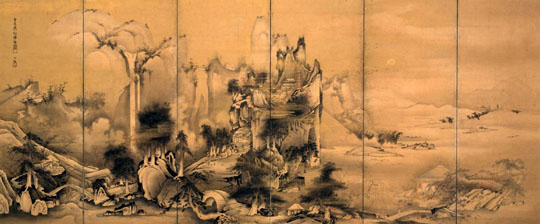

Since the Heian Period (794-1185), landscapes have served as the inspiration for generations of Japanese painters. Many followed the standards and styles of a particular school, while other — often encouragingly eccentric — individuals broke with all conventions to wield their brushes in a completely new manner. The Fuchu Art Museum is now hosting "250 Years of Edo Landscape Paintings," an exhibition showing Edo Period (1603- 1867) landscape paintings that have been selected with a flair for the unusual that we have been used to seeing at that other mecca of Edo culture, the Itabashi Art Museum in north Tokyo.

Landscape paintings can be divided into those that illustrate an actual place and those created from imagination, and artistic license has in many instances blurred the division between the two. Much influence came from China, and can be seen in early Yamato-e (Japanese pictures) inspired by Tang dynasty (618-907) mainland prototypes that depict mainly court scenes in palaces and beauty spots around Kyoto; later in the Zen-inspired ink landscapes of the Muromachi Period (1333-1573); and more recently in Edo Period Nanga (Southern painting) scenes employing the flamboyant brushwork of Ming dynasty (1368-1644) literati artists.

Naturally, the landscape has long been a favored subject for artists in those Asian and Western countries located in temperate zones where seasonal changes provide an infinite variety of color and light. As challenging as it is to copy realistically in pigment, more gifted artists have attempted to capture atmosphere and the subtle play of light on sky and space. Lines and forms also provide an wide array of material for the artist, as can be seen in the monotone drawings of Rembrandt (1606-1669) or the ink paintings of China, Korea and Japan. Those who have studied drawing know that beauty and interest can even be found even in the tangle of power and telephone lines (although that doesn't excuse covering the country with them).