They can't see the forest for the trees.

Watching pundits both near and far weigh in on Ichiro Suzuki surpassing the 200-hit plateau for a record 10th straight season over the past week has been a test of patience.

The stories have inevitably turned to Pete Rose — who also had 10 200-hit seasons in his career — and a statistical comparison of his achievements with the star of the Seattle Mariners.

What has been lost in all the hyperbole is that while Ichiro is a superb batter, with a strong arm and solid glove, he is just not in the same league that Rose was as a player.

Those of us who grew up when Rose was in his heyday can attest to his singular superiority and bristle when people try to compare Ichiro to him. An All-Star at an unprecedented five different positions, the legendary Rose set the standard for guts and rightly earned the nickname "Charlie Hustle" from the media.

It is impossible to compare Ichiro and Rose's stats in any realistic way, because they played in different eras and different countries.

Ichiro played the first nine years of his pro career in Japan, where the standard of play, though far improved from Rose's day, is still not on par with the major leagues.

How about analyzing Ichiro and Rose's stats just from their time in the majors?

That doesn't work, either, because when Ichiro saw his first pitch in the big leagues, he was in his 10th season as a pro.

Imagine the switch-hitting Rose, with 10 years of experience at a senior level under his belt, stepping to the plate in the show for the first time.

Think his numbers might have been even better?

Nobody seems to have the guts to say what needs to be said — that Ichiro plays for stats, while Rose played to win.

Of course Rose is remembered — on the field — for holding Major League Baseball's all-time hits record (4,256) and his 44-game hitting streak in 1978. But these accomplishments didn't define him.

It was the way that Rose played the game that resonated with the masses. He won the World Series three times and was a true leader.

While Ichiro's performance and courage in sparking Japan to the World Baseball Classic title in 2006 and 2009 were admirable, judging leadership on the basis of a few weeks in an event held once every three or four years doesn't equate with doing it for years in the majors.

It was nothing short of amazing watching the buildup in the Japanese media over Ichiro's latest push to 200 hits . . . while his team was on the way to a possible 100-loss season.

The bottom line is that Ichiro is a great player who puts himself first.

Save the arguments about him playing on a bad team. If he had a burning desire to win, he would have departed Seattle long ago.

The reality is that he is content to be a big fish in a small pond in the Great Northwest. That is his prerogative, but I think it says something about what he thinks is important.

It reminds me of a story about another outstanding batter — Hall of Famer Tony Gwynn — that I once read.

Gwynn, the former San Diego Padres star, was apparently notorious for sulking when he had a bad day at the plate, regardless of how his team did.

"You wouldn't believe this guy," a former teammate once said. "He walks around with his head down if he goes 0-for-4 and we win. If he gets three or four hits, and we lose, he is happy as a clam."

That is the kind of attitude that teammates resent.

You see, there is more to being a great player than being a record-setting hitter. Baseball is a team game.

This is why it was no surprise to hear talk of clubhouse dissension surface surrounding Ichiro back in spring training of 2009.

Allies of Ichiro quickly tried to downplay the issue, but the chatter that unnamed teammates "wanted to get physical with Ichiro" clearly showed a schism in the clubhouse existed.

It has been said that manager Don Wakamatsu, who was fired by the Mariners in August during his second season at the helm, was even brought in to pacify Ichiro after his rocky relationship with previous skipper Mike Hargrove.

What I keep coming back to is that Rose was all about the team. His play spoke for itself and teammates never questioned his desire or motivation.

Have you ever seen Ichiro slide into second base to break up a double play and come up scrapping?

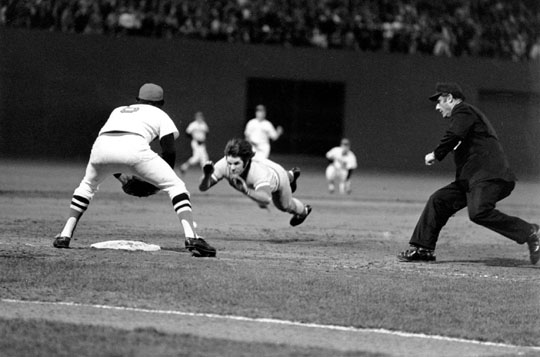

How about dive headfirst into third base?

Run over the catcher at home plate?

The answer to all of the above is "no."

Does this mean he is not a Hall of Fame player?

No.

But it also illustrates how Rose was consumed with winning and not stats. If he only cared about his batting average or hit total each season, he would not have played with such reckless abandon.

In the final analysis, those of us who have been fortunate enough to see both Rose and Ichiro play in their prime know there is really no comparison at all.