North Korea's test of a new intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) on May 14 is important for the United States for two main reasons. First, it appears that Pyongyang is now capable of targeting Andersen Air Force Base on Guam in the Western Pacific with a ballistic missile, although it remains unclear how accurate the new Hwasong-12 IRBM is. Second, the Hwasong-12 launch — given that it possibly involved the test of an intercontinental ballistic missile subsystem — may prove to be a major stepping stone in the North Korean quest to threaten the U.S. mainland with nuclear weapons.

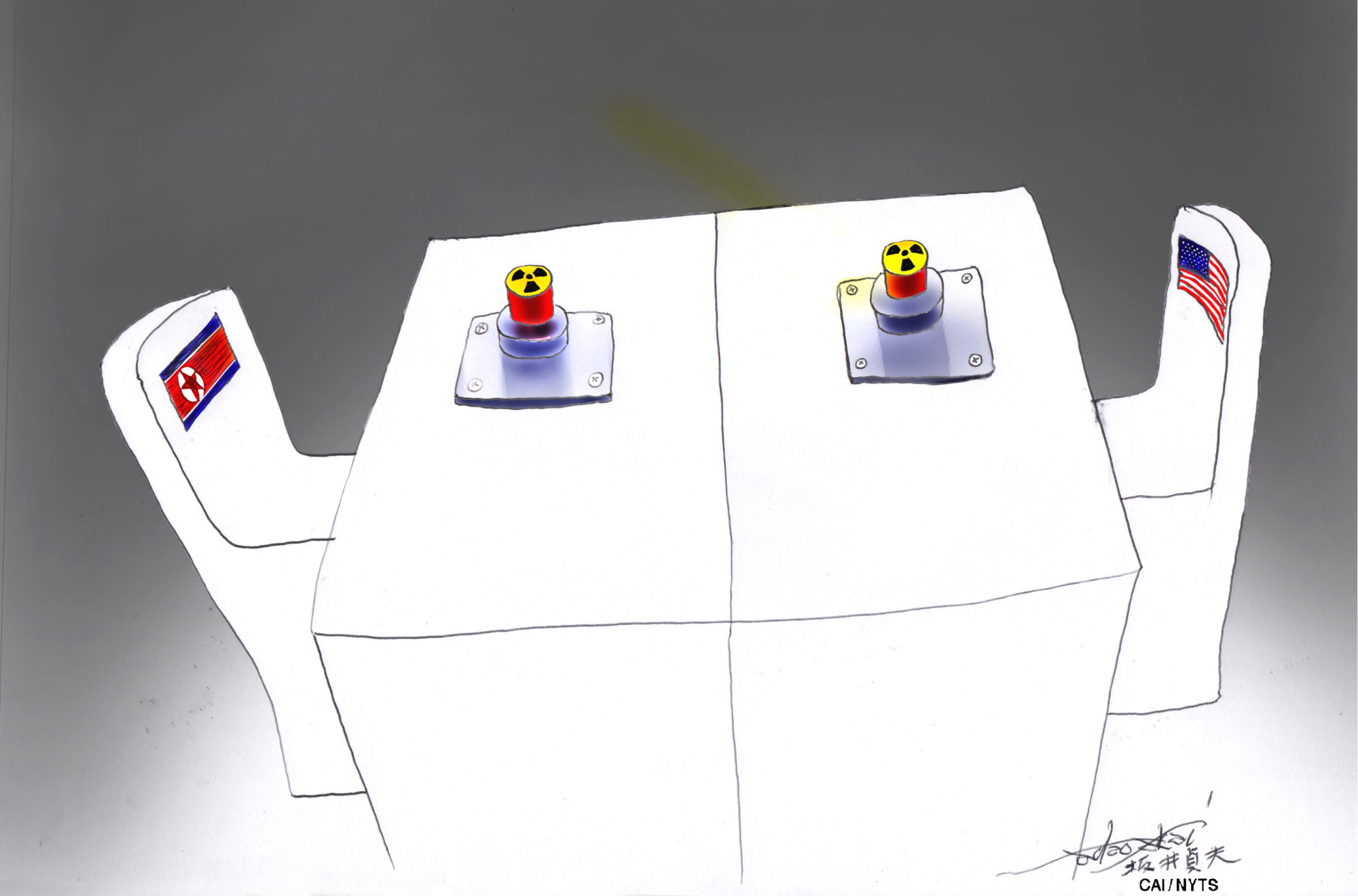

Indeed, it is the latter threat of an ICBM hitting a major U.S. city that for obvious reasons has been the primary concern of Washington policymakers ever since North Korea conducted its first nuclear test in 2006. Through sanctions and restrictions on technology transfers, the international community was so far only able to delay and increase costs for North Korea, but otherwise has failed to stop the country's nuclear ambitions.

Like hapless protagonists in ancient Greek myths who irrevocably meet their inevitable fate, the outcome in the current drama appears to be preordained and there is only speculation when rather than if North Korea will develop an ICBM capability, with estimates ranging from two to five years.