In a 2017 Elsevier report, "Gender in the Global Research Landscape," Japan ranks at the lowest end among 12 countries, with 15 percent female representation in the STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) fields. As the American daughter of an MIT engineering student, I grew up believing that I didn't have my father's STEM mind, so I completed a Ph.D. in the social science field of politics and international relations. But overall, U.S. women comprise over 40 percent of researchers.

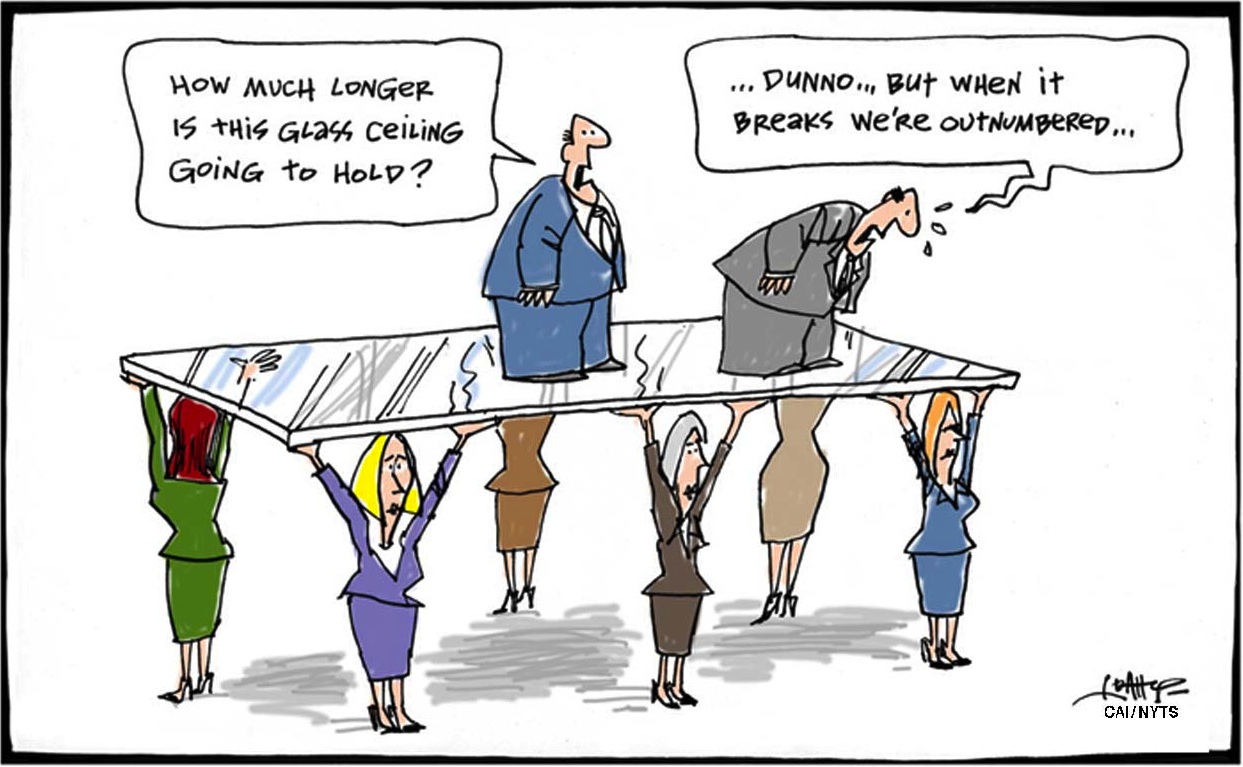

Japan has a global image problem in women's empowerment and participation from the science lab through the corporate suite to the ivory tower. This chronic condition is not just an economic drain but a global embarrassment. It can be improved by Japan's choice to take the lead in gender diplomacy. Gender diplomacy recognizes the power of gender analysis and gender equality promotion in international relations policy. And Japan's women are leading this cause in their preference for embracing the globe in work, exchange and study.

The Elsevier report shows that in places like Brazil and Portugal, nearly 50 percent of all researchers are women. Along with the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, France and Denmark have over 40 percent female researchers. But in Japan, men dominate: energy (9 percent women), engineering (11 percent women), and mathematics (11 percent women). Women's inequality in Japan is not something that will change with "womenomics" or women's conferences. There are cultural, political and economic conditions in Japanese society that continue to stymie Japan's "growth" in equality between men and women. It wasn't until 2016 that the Act on Promotion of Women's Participation and Advancement in the Workplace was fully enacted into law. This was 30 years after equal opportunity for men and women in the workplace was made official and 17 years after the Basic Act for Gender Equal Society.