Last month, 12 countries on both sides of the Pacific finalized the historic Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement. The scope of the TPP is vast. If ratified and implemented, it will have a monumental impact on trade and capital flows along the Pacific Rim. Indeed, it will contribute to the ongoing transformation of the international order. Unfortunately, whether this will happen remains uncertain.

The economics of trade and finance that form the TPP's foundations are rather simple, and have been known since the British political economist David Ricardo described them in the 19th century. By enabling countries to make the most of their comparative advantages, the liberalization of trade and investment provides net economic benefits, although it may hurt particular groups that previously benefited from tariff protections.

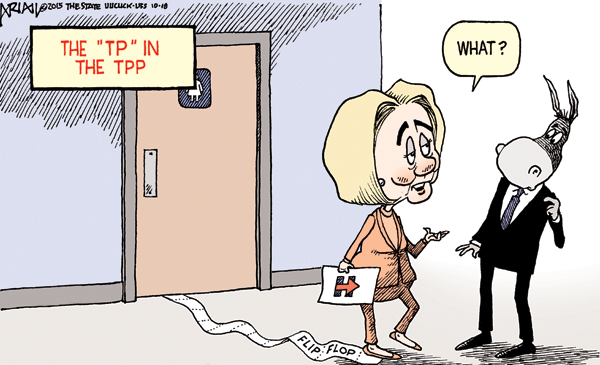

But the politics of trade liberalization — that is, the way in which countries proceed to accept free trade — is much more complex, largely because of those particular groups it hurts. For them, the overall economic benefits of trade liberalization matter little, if their own narrow interests are being undercut. Even if these groups are relatively small, the discipline and unity with which they fight trade liberalization can amplify their political influence considerably — especially if a powerful political figure takes up their cause.