The latest round of wrangling between Greece and its European creditors has demonstrated yet again that countries with such disparate economies should never have entered a currency union. It would be better for all involved, though, if Germany rather than Greece were the first to exit.

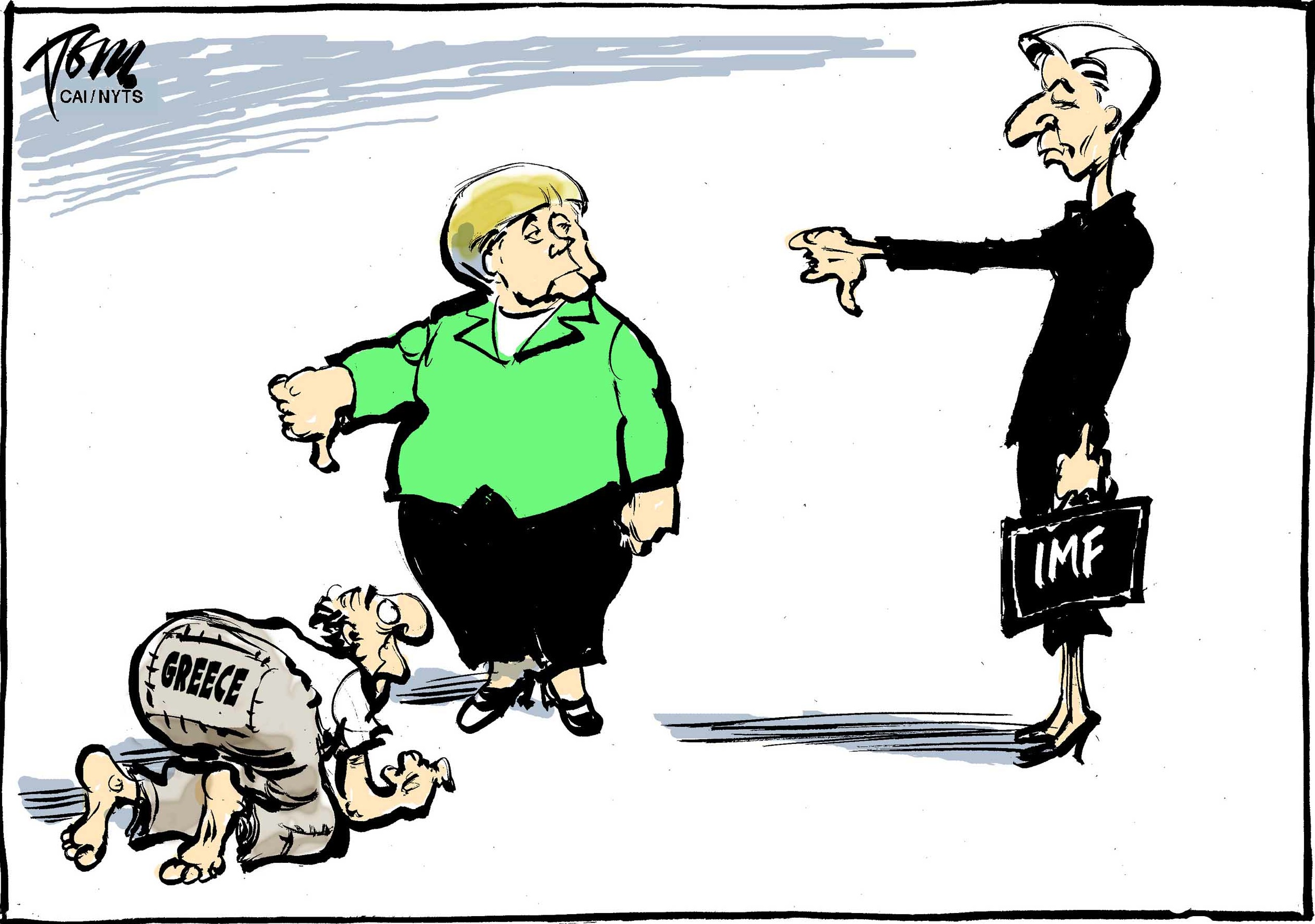

After months of grueling negotiations, recriminations and reversals, it's hard to see any winners. The deal Greece reached with its creditors — if it lasts — pursues the same economic strategy that has failed repeatedly to heal the country. Greeks will get more of the brutal belt-tightening that they voted against. The creditors will probably see even less of their money than they would with a package of reduced austerity and immediate debt relief.

That said, the lead creditor, Germany, has done Europe a service: By proposing the Greece exit the euro, it has broken a political taboo. For decades, politicians have peddled the common currency as a symbol of European unity, despite the flawed economics pointed out as far back as 1971 by the Cambridge professor Nicholas Kaldor. That changed on July 11, when European finance ministers agreed that it could be both sensible and practical for a member country to leave. "In case no agreement can be reached," they said, "Greece should be offered swift negotiations for a time-out."