Keishi looks a lot like it did when Toshiko Nakamura first moved there four decades ago. The quiet farming community in Nagano Prefecture is a patchwork of verdant rice fields, lush kitchen gardens and picturesque post-and-beam houses nestled between pine and chestnut trees on the slopes of Mount Hijiri. Although it's officially part of the prefectural capital, Keishi seems to belong to a different century than the busy city center an hour's drive away.

Sitting in her living room for a cup of tea and a chat, however, 74-year-old Nakamura says that her hamlet has changed dramatically over the years.

"We used to cultivate the rice paddies with a horse-drawn plough," recalls the widowed mother of two. "These days tractors drive around in the fields just like cars. A lot has changed."

Nakamura moved to Keishi in 1972 to live with her husband and his parents. She shared a modest home with five family members, farmed part time and worked at a liquor shop nearby. Although she and most of her neighbors grew their own food, traveling merchants passed through several times a week hawking their wares. The hamlet bustled with kids and animals.

Today not a single child lives in Keishi, and almost all of Nakamura's neighbors are elderly. Her son lives in Tokyo and her daughter in another city in Nagano. With shops nearby shut down, she drives about 50 km round-trip to buy groceries each week. She plows her fields with a tractor and lives alone in a house with a jet bath and floor heating that she and her husband built after he retired.

In other words, her life is a lot more energy intensive than it was 40 years ago. This is in part due to changes in her lifestyle and the technology she uses. However, it's also in part due to the fact that Keishi's population has shrunk while its infrastructure has remained largely the same.

The same thing is happening in communities throughout Japan, which is on track to lose people faster than almost any other place in the world in the coming decades. For policymakers struggling to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the face of accelerating climate change, rising home energy use alongside a declining population is a complicated puzzle with implications for planning and sustainability in the coming century.

Climate-change models have long assumed that when population declines, energy use will contract in tandem. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that this simple one-to-one relationship may not be accurate.

"The expectation is that withdrawal of people will lead to a natural and easy gain in areas such as energy consumption, carbon output and biodiversity loss," says Peter Matanle, a sociologist at Britain's University of Sheffield who is researching the relationship between energy use and population loss in Japan. "What's very interesting about Japan is that when we look at all these issues, they don't seem to be happening in that way."

Number crunching

Global population will likely grow to between 9.6 and 12.3 billion people by 2100, according to the most recent projections from the United Nations. Other demographers argue the peak will take place lower and earlier, possibly around 2075. Whichever scenario turns out to be true, these extra humans will almost certainly generate ballooning quantities of greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change. They will also demand more land to feed and house, putting pressure on forests that are crucial for absorbing carbon dioxide.

Africa is expected to be the major growth hot spot, but population will not grow evenly around the world. Population is already contracting in more than a dozen countries, including Germany, Cuba and most of Eastern Europe, due to a combination of low birth rates and emigration. Over the coming century, more will follow as fertility rates fall. Even China, the world's most populous nation, is likely to begin shrinking around 2030. The average age is expected to rise worldwide in the coming decades as well.

Japan — where national population peaked in 2008 and many rural areas began shrinking decades earlier — is at the forefront of these trends.

Leiwen Jiang, a demographer at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in the U.S., acknowledges that the international climate-modeling community does not yet know how demographic decline will impact energy use.

"Unfortunately, in the past most countries have experienced (only) population growth," says Jiang, who is working to refine the center's climate model to better reflect demographic realities. In the absence of empirical data on depopulation, he says, researchers trying to project into the future usually extrapolate from what they know about how population growth has affected emissions in the past.

That relationship turns out to be surprisingly simple. Historically, data show that a 1 percent increase in population has been associated with about a 1 percent increase in carbon-dioxide emissions. That's in addition to impacts from technology, affluence and other factors. Currently, most climate models assume the same one-to-one relationship will also hold true in reverse.

However, Jiang warns that models whose demographic component only looks at the total number of people in a country may not accurately predict energy use. "Other demographic dynamics can be as important as total population growth, such as aging, urbanization and household composition changes," he says.

Matanle believes Japan is the perfect living laboratory in which to gather data about those complex dynamics, for several reasons.

First, over half the land area in Japan has been losing population for at least 20 years, a trend he says is "very unusual worldwide" yet "almost certainly going to happen in increasing numbers of countries from now on in the 21st century" due to processes including urbanization and better female education.

Second, the government collects meticulous statistics on both demographics and energy use. Third, Japan has been a stable democracy for more than 50 years, meaning fewer major jolts to its demographic development.

Finally, the specific pattern of demographic change observed in Japan — steep growth followed by steep decline and rapid aging — appears to be playing out in China as well. As China is the largest carbon emitter in the world, population and energy shifts there matter globally. Japan could provide valuable lessons on how to make the most of coming demographic decline.

Already, scattered research is providing some surprising insights.

Earlier this year, researchers at the International Center for the Study of East Asian Development in Kitakyushu looked at how aging impacts carbon-dioxide emissions in urban areas. Comparing household emissions in 709 Japanese cities (excluding Tokyo), they found higher levels in cities with more elderly people. These cities also turned out to have smaller households. They concluded that aging had contributed to the proliferation of homes with just one or two people living in them — elderly men and women like Nakamura inhabiting houses once filled with multigenerational families. That, in turn, led to higher per capita home energy use.

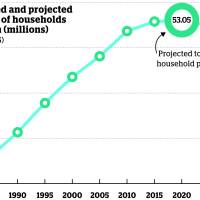

Nationwide, more Japanese are living alone for a number of reasons — among them aging, urbanization, later marriage age and rising divorce rates. The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research projects that by 2035, the country's population will fall by 13 percent, but the number of households will only fall by 4 percent.

"The largest impact is from labor participation and productivity," Jiang says. "If you have an aging population, labor productivity will decline."

That means the entire economy will likely slow, overshadowing the impacts of elderly people living alone or, say, taking more hot baths. In a 2006 paper published in Energy Economics, Jiang and four co-authors projected that in the United States, aging could eventually reduce carbon-dioxide emissions by almost 40 percent. That's far from a foregone conclusion, however; other researchers have suggested that education and innovation could keep graying economies buzzing — and emitting.

Less carbon dioxide is more

Where people live in relation to one another matters, too. When researchers at the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism charted per capita carbon-dioxide emissions from motor vehicles against population density in 2010, they found a strong correlation. Not surprisingly, residents of Japan's most crowded cities — Osaka and Tokyo — produce the least carbon-dioxide emissions from driving.

Conversely, as population thins in rural regions, people often need to drive further to reach stores, schools and hospitals. That may be one reason why, when Matanle took a preliminary look at energy use by prefecture in 2013, he found per capita energy use increasing faster in prefectures where population was shrinking than those where it was growing.

Another explanation, he suspects, lies in the government subsidies that shrinking regions receive to shore up employment by building new factories and offices.

"Much of Japan is still locked into the local revitalization movement, so nearly every town, village and city still wants to grow," Matanle says. Nationally, the government is battling demographic decline through a raft of pro-growth policies, including direct subsidies for each child born.

The perplexing patterns Matanle is starting to detect in the country are familiar to Reiner Klingholz, director of the Berlin Institute for Population and Development in Germany — one of the few other countries aside from Japan to have begun experiencing the environmental impacts of depopulation.

"So far the simple formula 'fewer people equals less destruction' has failed to materialize in practice. For wherever people live further apart, transportation routes become longer, and water pipes and roads that hardly anyone uses have to be maintained at great expense," Klingholz wrote in a 2013 report on "planning for de-growth" in Germany.

The problems are especially acute in former East Germany, where population drained away suddenly following the collapse of the Soviet Union and left behind oversized, resource-sucking water systems and other infrastructure. Klingholz believes Germany's government needs to re-think planning and public policy in order to begin reaping "ecological dividends."

"You can shut down roads that are not used, you could change wastewater systems from centralized to decentralized systems, you can close some infrastructure like schools or hospitals, you can use different ways of providing the infrastructure," Klingholz says.

He even suggests cutting off public services from some extremely depopulated areas and relocating their residents to town centers — a hard sell given people's powerful attachment to their native place and politicians' desire to keep rural votes.

Homesteading redux

The city of Toyama, located on the coast of the Sea of Japan about 200 km north of Nagoya, is a prominent example. Ten years ago, it had the highest inner-city car use in the country, and carbon emissions were increasing at a rate twice the national average. Urban sprawl was the main cause of these problems, but aging promised to accentuate them: by 2040 the city is projected to lose 20 percent of its population. City officials were desperate to lower running costs before that happened. So in 2002, they began implementing compact city planning. The goal is to draw people into a string of walkable urban centers arranged around several main public transport axes (the city calls this the "shish kebab model"). The strategy is based on inducement rather than regulation. By improving light rail and other public transport, and offering subsidies for housing nearby, the city hopes to reduce carbon emissions by 30 percent by 2030. The policies won Toyama designation as one of Japan's 20 Environmental Model Cities in 2008.

Tomio Yoshikawa, an economist who has researched smart growth and urban decline in Japan and the United States, says that sort of plan may be effective in urban centers, but not in outlying areas where depopulation is happening fastest.

"In Japan, no matter where you are, municipalities have a responsibility to provide services such as water and roads that emergency vehicles can use," Yoshikawa says. That means that unless incentive programs work perfectly, the government must maintain a certain level of infrastructure in countless small, scattered communities such as Keishi.

"For a village of 10 people, the government spends a huge amount of money and energy. And 80-year-old couples are not going to move into the city based on incentives alone," Yoshikawa says.

"You come to love the place where you live," she says. "I haven't given up. For now, I can still drive, and my kids help me out."

Matanle acknowledges that's a challenge — and that proactively draining the countryside of its remaining residents might not be the best idea in cultural or environmental terms. Still, he sees enormous potential for Japan to reap what he calls a "depopulation dividend."

"It's entirely possible that with urban, economic and housing planning, we can get environmental benefits and improvements in living standards out of depopulation," he says.

For that to happen, Japan will have to start devoting a lot more creative thought to the question of how to shrink wisely.

This article was produced in partnership with Climate Confidential as part of its "Local Edition" series.