Locations around the globe will soon reach climatic tipping points, with some in tropical regions — home to most of the world's biodiversity — feeling the first impacts of unprecedented eras of elevated temperatures as soon as seven years from now, according to a study released Wednesday.

On average, locations worldwide will leave behind the climates that have existed from the middle of the 19th century through the beginning of the 21st century by 2047 if no progress is made in curbing emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases, said researchers at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, who sought to project the timing of that event for 54,000 locations.

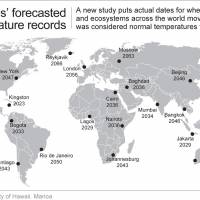

If they are correct, the transition would occur by 2020 in Manokwari, Indonesia; by 2023 in Kingston, in the Caribbean; by 2029 in Lagos; by 2047 in Washington; by 2066 in Reykjavik; and by 2071 in Anchorage, Alaska.

"The boundary of passing from the climate of the past to the climate of the future really happens surprisingly soon," said Christopher Field, director of the Department of Global Ecology at the Carnegie Institution for Science, who was not part of the research team but has read the study, published in the journal Nature.

Researchers said at a news briefing that their estimates are "conservative," based on mountains of data from 39 different models and accurate within five years in either direction for any of the locations they studied.

Although scientific research shows more warming occurs nearer Earth's poles — and the melting of Arctic ice sheets is the iconic image of a warming planet — the tropics are especially vulnerable because even a small change in climate will affect a wide range of species. It is also alarming because the area around the equator is home to billions of people in poor nations with fewer resources to help them cope.

The new study is hardly the first to document the steady march toward hotter temperatures around the globe. Less than two weeks ago, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its fifth report, describing a planet that is warming at an accelerated pace because of human activity.

The past three decades have been the hottest since 1850, according to the panel — established by the United Nations — which added that warming and sea-level rise will continue through the 21st century.

But by predicting the tipping point when traditional climates will be replaced by hotter futures, the new study's group — led by Camilo Mora, an assistant professor in the geography department of the University of Hawaii at Manoa — provided a fresh way to look at a problem that often is seen as a global phenomenon, except by authorities who must respond to the increasing toll of floods, droughts, wildfires and severe weather, experts said.

"I think people don't appreciate the fact that one of the metrics we are most familiar with, and definitely have the most difficulty dealing with, extreme heat, is coming down the track," said Michael Oppenheimer, a professor of geosciences at Princeton University.

"The people who are going to be really hard hit are in developing countries. But I wouldn't say the U.S. is exactly safe," he added.

Judith Curry, chairwoman of the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology, who has questioned the accuracy of climate modeling, said she found the Mora team's conclusions "less alarming than the IPCC's analysis" and thought the study's methodology was compelling.

Under the best of circumstances, the climate change milestone worldwide will be reached by 2069, even if nations manage to hold the emission of carbon dioxide to a much lower level, the authors said.

Once any location reaches the tipping point, the average temperature of its coolest year will be greater than the average temperature of its hottest year between 1860 and 2005, the period set by the researchers as their baseline for comparison. Sea levels will continue to rise, and oceans will continue to become more acidic, they said.

They also said acidification of world oceans has already changed their traditional climate, in 2008.

Mora and colleagues Abby G. Frazier and Ryan J. Longman wrote that because the tropics experience so little variability in climate, it will take less warming there to cause noticeable change, and it will happen sooner.

"I am certain there will be massive social and biological consequences." Mora said. "The specifics I cannot tell you."

In their study, the researchers wrote: "The tropics will experience the earliest emergence of historically unprecedented climates. This probably occurs because the relatively small natural climate variability in this region of the world generates narrow climate bounds that can be easily surpassed by relatively small climate changes.

"Tropical species live in areas with climates near their physiological tolerances and are therefore vulnerable to relatively small climate changes," they added.

Longman said tropical species affected by climate change will have three choices: Adapt, move or become extinct.

"Considerable changes in community structure and extinction have been shown to have coincided with the emergence of unprecedented climates in the past," the authors wrote. "In addition, recent short-term extreme climatic events have been associated with die-offs in terrestrial and marine ecosystems, highlighting the potentially serious consequences of reaching historically unprecedented climates."