When a thing of beauty is perceived, the observer experiences some kind of a reaction; but what defines "beauty"? Is it art?

Some react with pleasure at horror, others at farce, yet more to romance; each is an art form — but how do we define "art"?

When works such as U.S. minimalist Carl Andre's 1966 "Equivalent VIII" (comprised of 120 firebricks), street graffiti by contemporary British guerrilla artist Banksy, or dissected and "plastinated" human remains a la German anatomist Dr. Gunther von Hagens' "Body Worlds" show that debuted in Tokyo in 1995, are all displayed in the name of art, then we face at the very least a conundrum, at times a controversy.

Perhaps art is anything represented or depicted, or enhanced. But perhaps it can only be defined in the negative, by what it is not; art serves no purpose; it is not practical.

Is art what the artist decides, or is it entirely dependent on the "I" of a beholder?

Whether it appears in two or three dimensions, and regardless of the medium, anything created that involves human imagination may be "art."

What then of the colorful patternings of Congo (1954-64), London Zoo's chimpanzee encouraged to draw and paint by zoologist Desmond Morris, or of TEAG (The Elephant Art Gallery), which works with Asian elephant artists at the Elephant Art Academy of the Thai Elephant Conservation Center?

Are these also art, even when they do not involve human imagination in their creation? Are childlike crayon scrawlings that we consider nothing more than play in a young human, really high art if they are the work of an established adult artist? If "art" may be created on a cave wall, on parchment, paper or on an iPad, the medium, whether analog or digital, is clearly irrelevant — as long as the image evokes, or provokes, a response.

So is art somehow defined by the quality of that sentient, imaginative response in the mind of the observer? Is sentience a prerequisite in the creator of a work of art?

If nature somehow casts a heavy brush of crystalline frost glinting across a wide winter landscape in a "work" that conjures images of trillions of scattered scintillating diamonds, is that not art? If not, what is it?

If nature drapes deep snow, shroudlike, around living trees, isn't that also art?

When ice forms ranks of subtly variant Moomin-like stalagmites in a shady cave, or if myriad leaves in vibrant fiery colors appear to flow down an autumnal mountainside, is that beauty no less artistic — or does the absence of sentience deny it that attribute?

If a viewer responds and finds it beautiful, doesn't that make it art?

If nature, in the long process of adaptive evolution, crafts and hones a killing claw, a ripping talon or a tearing beak, are those weapons of predatory "horror" somehow less significant as art than the suspense-horror of Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho"?

The gorgeous eyes of a peacock's tail, the startling iridescence of a beetle's wing, the amazing microscopic structure of a pollen grain's surface: Each is undeniably exquisite, yet we rank them apart from any human attempts to portray an essence of beauty.

Why? Well, art clearly raises more questions than it can answer, but perhaps that is the true interpretation of its "meaning."

As a nature-lover, I am an unashamed lover of nature art — art that depicts elements of nature, that transports me to the scene of the imagining and engenders a response. Now that is an art I can deeply appreciate.

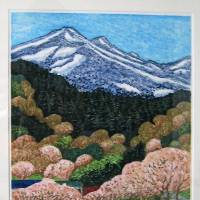

A landscape print by contemporary woodblock artist Hiroshi Hosomi transports me into the scene. Subtle shades, hinted contours and fragmentary images suggest — and as my imagination supplies the rest, I can sense the sounds of the landscape and its scents and imagine the weather changing the view — all thanks to my own personal experience of the very same locations the artist has depicted.

The connection is a strong one because of that shared personal experience between artist and viewer.

In the creation of a swan flute, people in prehistory who whittled those large birds' wing bones into complex musical instruments surely sought — likely by trial and error — the notes their labor might produce. Then they bent their will, and their attention, into the detail of what they shaped and into the music it produced.

Shaping, carving, creating, tuning and ultimately playing all led to the beauty of the instrument — in this case a 35,000-year-old bone flute such as that I saw at the Wurttemberg State Museum in Stuttgart, Germany, and which was such a moving experience that I will never forget it. It was a wonderful reminder that our race's penchant for cruelty and destruction is matched by kindness and great artistic creativity.

Some, like Hosomi, capture the essence of a landscape in a print; for his part, sculptor Yasuda Kan creates amorphous 3-D shapes that somehow transcend perception so as to, through the eye, by some means please our tactile sense.

Others, such as Hokkaido artist Hisashi Masuda, are capable of confining their creativity through the fine hairlike strokes of a brush or pen-and-ink illustration while yet, for instance, capturing the bulk and power of a bear, the shiny smoothness of an acorn or the delicacy of a blossom.

If art is a personal response, then I respond equally to all three.

Wildlife artist Masuda, a native and resident of Hokkaido, portrays the natural world through brush and pen. His subjects are mainly from his home island, but also from regions northward in Russia and Alaska.

Born in 1972, Masuda became interested in birds, other animals and the natural world after seeing Crested Kingfishers and Red-crowned Cranes in Hokkaido when he was 16. Now he is as accomplished in portraying the plumage of a Ural Owl as he is in capturing on paper a pacing Brown Bear, a Eurasian Red Squirrel's fur or the spent beauty in a fallen autumnal maple leaf.

Deeply impressed by the works of the American and Canadian wildlife artists Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009) and Robert Bateman (1930-), respectively, Masuda works in similar vein, contributing to both magazines and books and frequently exhibiting in Sapporo and Tokyo. For his monochrome art, he uses pen with ink and pencils; in color he mainly uses acrylics.

Fortunately, I have been able to enlist this remarkable artist to illustrate my upcoming collection of essays titled "The Nature of Japan." His drawings, made over three years, not only illustrate those stories collated from more than 30 years of writing, but they stand in their own right as beautiful portrayals of species dear to my heart.

Mark Brazil has written Wild Watch for more than 30 years. As the founder of Japan Nature Guides, he organizes and leads photographic, birding and wildlife excursions nationwide. His books, including "Field Guide to the Birds of East Asia," "A Birdwatcher's Guide to Japan" and "The Birds of Japan," are available from good bookstores or directly via www.japannatureguides.com.