Sitting in the welcoming confines of Hideyo Miyamoto's delightfully decorated cafe as his exquisite sound system enhances the coffee and its refined ambience, it is not difficult to imagine that the 75-year-old owner of Chopin in Tokyo has devoted five decades of his life to making classical music accessible to all in Japan.

With 33 books, seven years as a record producer, three decades as a highly sought-after lecturer and 31 years under his belt as a cafe owner dedicated to serving up classical masterpieces with a cup of Joe, Miyamoto is an apparently contented man.

But life wasn't always this easy, and Miyamoto admits that after his parents divorced in 1947 when he was 10, when his father tried to prevent him from attending university when he was 18, suicide seemed the only avenue open to him.

After barely recovering from a burst appendix that was so infectious the surgeons refused to give him anesthetic before operating because they feared he would die, Miyamoto took a train to Hakone, the hot springs resort in Kanagawa Prefecture, fully expecting to end his life with sleeping pills.

But as he sat in what he planned to be his last bath, the strains of Bach's "Chaconne" for solo violin drifted in from a nearby window.

"The tender, kind and strangely serious melody of the 'Chaconne' lasted some 15 minutes, absorbing and overwhelming me," he said. "I felt as if the piece were continually telling me that it understands my feelings.

"When I finally came to myself, I found I was shedding tears and sitting naked and motionless in a corner of the bathroom with the quietness of the night surrounding me. Deeply moved, I again took a dip in the hot water and stayed there absent-mindedly until, after returning to my room, I decided to live on," he said.

Bach literally saved his life, he believes.

In those days, when meikyoku kissa (classical music cafes) were more prevalent in Tokyo, Miyamoto and thousands like him let go of their anxieties and soothed their minds relaxing in the cafes and allowing themselves to be swaddled by the sounds of music that was generally far beyond their means. The average starting salary for a university graduate was ¥10,000 a month and an LP record sold for ¥2,500.

"A record player cost ¥20,000, or about ¥400,000 now, and a single classical concert was worth a month's salary for a university graduate, so the meikyoku kissa were places where youths could listen to classical music by ordering a ¥60 cup of coffee," he said.

But for Miyamoto and others, even ¥60 for coffee was steep. In 1956, he was making ¥7,500 a month at an auto repair company, studying at a university at night and helping his family. This meant limiting his own daily expenditures to ¥80.

But after being introduced to meikyoku kissa by a university friend, he began limiting his daily meal to a bottle of milk and some bread so he could afford the ¥60 coffee and enjoy the classical music that he said touched him almost from the first chords he heard.

Buoyed by the Bach that saved his life, Miyamoto decided that classical music would become his life.

He returned to school, graduated as the valedictorian in 1961 and used his economics degree to find a job at Nippon Columbia Co.

After working his way into record production, he eventually opened a meikyoku kissa of his own where he could pass along the wonders he felt each time Wilhelm Furtwangler conducted Beethoven or Arturo Toscanini interpreted a classic.

His cafe, one of only about 10 meikyoku kissa left in Tokyo, is a testament to Miyamoto's dedication and passion.

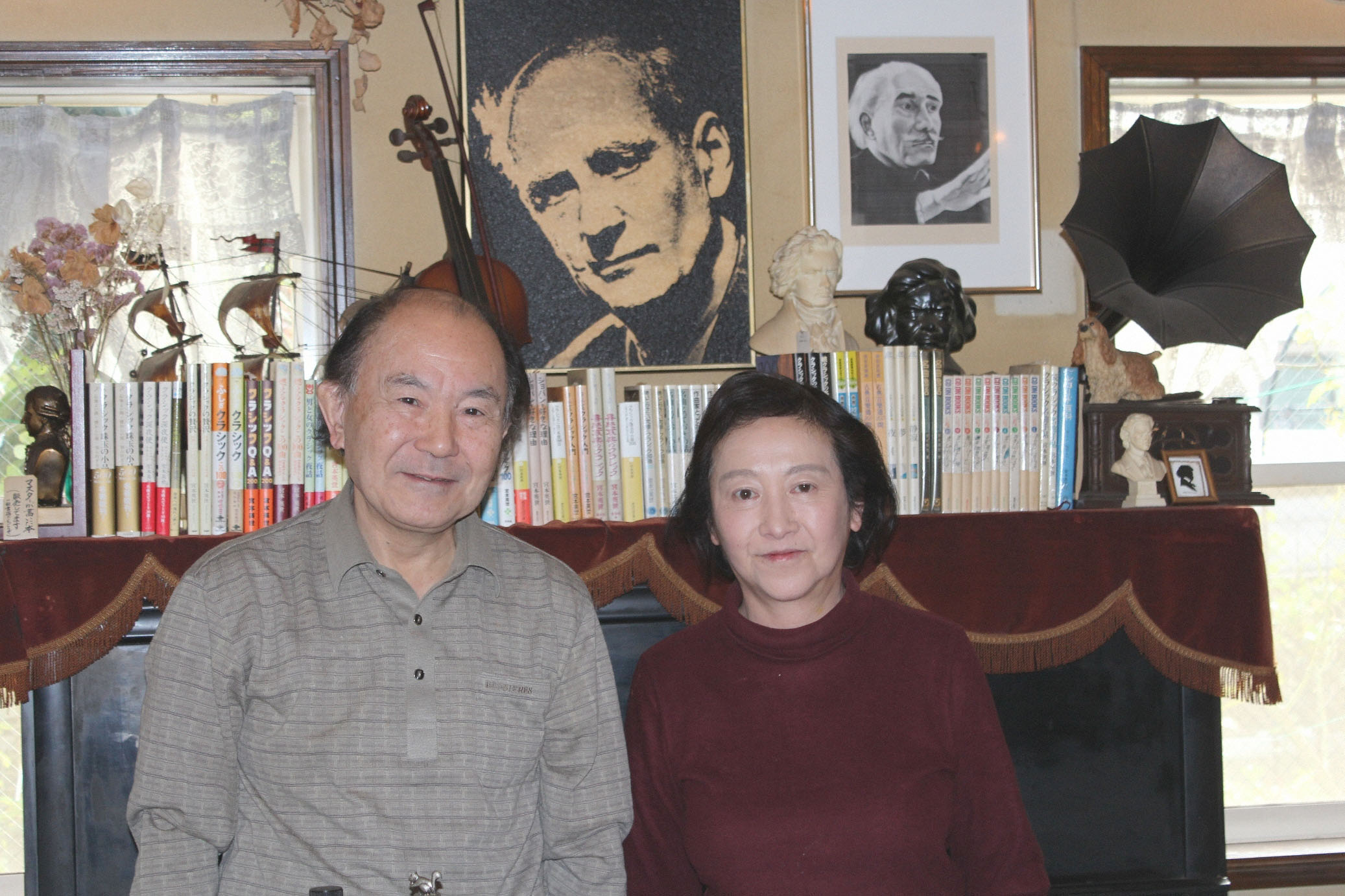

Cafe Chopin is furnished with a bust of Beethoven, a set of Tannoy speakers, pictures of Furtwangler and Toscanini, a reproduction of a photo of Chopin from 1849, and an upright piano in addition to the regular accouterments of a welcoming coffee shop.

There is also a picture of Miyamoto and French flutist Jean-Pierre Rampal when Rampal recorded a performance in Tokyo.

Miyamoto also became a prolific author of books on classical music and composers, bringing readers into the lives of those who made the music by revealing intimate details about them and presenting them not as giants, but as ordinary people with their own foibles and jobs.

Frederic Chopin composed the second movement of his F-minor Piano Concerto for student Constantia Gladowska when he was 19, and in love.

Miyamoto's book on Chopin highlights the bashfulness of the composer, who wrote to a friend: "In the six months since I first saw her, I have not exchanged a syllable with her of whom I dream every night."

Miyamoto also gives monthly lectures for music buffs, several of whom have been attending for 25 years.

During two-hour sessions, he plays CDs of various pieces and expands on the backgrounds of each and its composer.

"Miyamoto-sensei often encourages us to ponder what intentions and emotions the composer felt while writing the music," said Eiko Yamafuji, 77. "I think his explanations about the lives of composers have deepened my understanding of the music they composed."

"Many people have attended Miyamoto-sensei's courses because they have found his talks have rich content and are interesting," Chika Saito, 66, said.

Now, despite the sometimes torturous journey he took to becoming one of Tokyo's few remaining meikyoku kissa owners, Miyamoto said he is merely giving back.

"I have been able to come this far because I had an encounter with classical music. Honestly, I can say I have lived up until this day because Schubert and Beethoven gave their music to my life," he said.

And at Cafe Chopin, Miyamoto and his wife, Setsuko, continue to give others the same chance he had to live a life filled with music.